n.b. Welcome to part two of this essay on Tyroc, who in 1976 was only the third Black superhero introduced by DC Comics. Part one examined his introduction and subsequent use in two stories in the Superboy and the Legion of Super-Heroes series, to consider the projection of troubling attitudes around race into an idealized future and how the “race-neutral” ideal of that future (and thus our past) frequently serves to actually mark the Black character for problematic treatment. In this conclusion, Tyroc’s final pre-Crisis appearance is examined to consider the problems of even trying to address the troubling origins he was given.

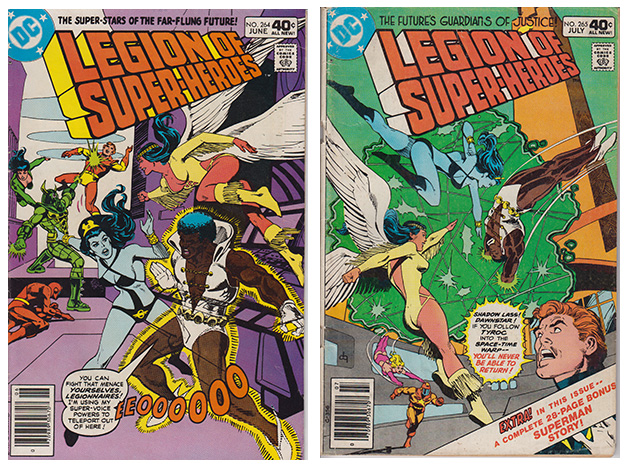

The cover of Legion of Super-Heroes #264 follows a common pattern of casting doubt on Tyroc’s honor or loyalty (like issue #222) before providing mitigating circumstances. On the cover of #265, Tyroc himself is painted as too dangerous to pursue or seek to keep within the Legion fold. (art by Dick Giordano).

Tyroc’s career as a Legionnaire is not a long-lived one. In part one of this essay, I explained how the use of race as a motif is implicit in the story included in Superboy and the Legion of Super-Heroes #222 (December 1976), wherein Tyroc’s apparent criminality is made believable by nature of his being Black and an outsider among the Legion. Comics like this make use of race to make a story seem plausible without digging into the racist perspectives that buoy it and such a pattern is present right up to Tyroc’s literal disappearance. This racialized approach is leveraged by a new creative team seeking to rehabilitate Tyroc’s origin even if in the end it also re-installs the segregation that marked his intro. Legion of Super-Heroes #265 (July 1980) opens with Tyroc confronting Dawnstar and Shadowlass who have arrived in Marzal to seek him after he abandoned the Legion in the middle of one of their adventures. Unfortunately, the two Legionnaires have arrived just as Marzal begins to wink out of existence. In “Brigadoon Syndrome”—scripted by J.M. DeMatteis from a plot by Gerry Conway and with art by Jim Janes, Dave Hunt and Gene D’Angelo—Marzal is retconned to be like the legendary Scottish village of Brigadoon, shifting in and out of the world at different intervals. The entire island now floats in an “hallucinatory landscape” and to try to leave it could mean “tumbl[ing] forever through [an] eerie dimension.” In explaining what is happening to his fellow Legionnaires, Tyroc recounts the origin of Marzal, complicating the original premise of it being an island of Black isolationists, but nevertheless using race to access a story the comic would normally not be able to tell.

The origins of Marzal has its roots 1400 years in the past (relative to the 30th century), back when (according to the story) “the Black man lived in the jungle.” Sigh. So, that last part makes it clear, right? Even when the serialization of superhero comic book stories is put to work to try to course correct the problematic origins and arcs of Black characters, they nevertheless continue to include racist generalizations about Africans and their civilizations. The story may not call those taken as slaves “savages,” but the implication is there if a reader needs it to line up with already held perspectives on Black history.

Regardless, when Tyroc’s ancestor leads a slave revolt on a ship bound for the Americas, the Legionnaire suggests that the storm that helped them succeed was a sign that “nature herself had sided” with his people, again connecting Black folks to the so-called natural world in a way that is supposed to be dramatic and reverential but that (perhaps unintentionally) just reinforces stereotypical perspectives. Now controlled by the would-be slaves, the ship washes up on a paradisiacal island that they (with dubious joy) call their new home, quite understandably declaring that they will “Let no white men — or white devils — try to wrest it from us!” In that moment, the entire island slips into another dimension, making sure this proclamation comes true. In time, Marzal not only grows from huts to a fort to a city, but somehow—in a move that highlights the creators’ inability to envision progress outside of a Eurocentric perspective—independently develops the Anglo-European markers of civilization and progress like top hats, petticoats, and Victorian architecture! And it is around that time that the island shifts back to Earth’s dimension. This how the people of Marzal discover that their island does this for a period of 30 years about every two centuries.

In creating this origin, Conway and De Matteis completely overwrite and ignore Marzal’s introduction as bigot “separatists,” reframing their attitude as a response to the 17th century transatlantic slave trade. By the time the re-telling comes to Marzal’s most recent reappearance, however, Tyroc is describing himself and his people as “slowly coming to love the world” and being thankful that he became—sounding like Ariel the mermaid—“a part of that world,” because of the Legion.

If the idea that superhero comics have a rotating fan base that ages into and out of the hobby are to be accepted (and I think we have more reason to believe this was the case in 1980 than it is now), then I might imagine that four years after his troubling introduction, few readers would remember it. Furthermore, not including his introduction, this is just the third story in that time to feature him as more than just a background character (if at all). As such, this smoothing over of his introduction functions to excise the problematic parts without contradicting them, while maintaining the motif of racial grievance, even if it is flipped to correct for Bates’s reactionary take on “who is the real racist?” in issue #216. In other words, Tyroc’s race is still being used instrumentally here, this time in an over-compensatory way to explain both the island’s apparent invisibility before the first Tyroc story and its citizen’s attitudes towards white outsiders.

Despite being cut off from the rest of the world, Marzal’s development somehow perfectly paralleled the aesthetic of Anglo-European civilization.

Lastly, in a turn of events that seems to suggest that segregation or assimilation are the only choices for a Black community of the future, it turns out that Tyroc using his power in Earth’s dimension while aiding the Legion is weakening the walls between worlds. This is why Marzal slipped back into its limbo before the full usual 30 years was up. It seems his very attempt at integrating the Legion is being rewarded by having to choose between his homeland and the Legion. As such, he declares that he can never return to Earth or use his powers there for fear of trapping his people in the other dimension permanently. When Shadowlass comes up with a plan for creating an opening between universes allowing them to evacuate Marzal and all to return to Earth, Tyroc explains that while his people love the Earth, they would not leave their homes for it. So instead, Tyroc uses his powers to make an opening just large enough for the two Legionnaires to escape back to Metropolis.

It might be worth noting that it is Dawnstar’s super-evolved tracking power that allows her and Shadowlass to navigate the passage and make their way back to their home dimension—a tracking power that is an extension of the native stereotypes built into her own people’s origins. Dawnstar was introduced a year after Tyroc. It seems she is descended from indigenous peoples of the Americas who were abducted by aliens in the 13th century and released to populate another planet where genetic engineering triggered their “metagenes” and caused them to grow wings. But I will leave analysis of Dawnstar’s own status as a hyper-otherized caricature for another essay or better yet, for a scholar with more experience exploring issues of native representation in comics.

And then that’s it. Without even a goodbye, Tyroc and Marzal are gone forever (or at least for 200 years). Yes, he will return post-Crisis in other versions of The Legion of Super-Heroes and in Elseworlds stories, but those stories are discontiguous with this version of the character. Legion of Super-Heroes #265 does some work to “correct” Tyroc’s origins. It implicitly explains why despite never appearing in this vision of the 30th century before issue #216, Marzal must have been around. Furthermore, in giving the island nation a specific origin tied to a (fictionalized) account of an actual aspect of Black history, the comic book also suggests that the people of Marzal are not the only Black people of the 30th century (something issue #216 seemed to suggest), but rather just one community of them. Remember, there have been other Black people of the 30th century depicted in these comics since Tyroc’s introduction—specifically, the splash page that sets up the premise for issue #222 wherein we see two Black citizens of Metropolis in the angry mob jeering at Tyroc, one of which is throwing a rock at him. This opening page, however, is not an explicit part of the story, but an extradiegetic characterization of its premise, a formal feature that was already falling out of use in superhero comics by the late 1970s. This peripheral image establishes a difference between Marzal’s champion and those fully-assimilated Black people of the future without having to wade into the messy complications and contradictions of identity politics.

Legion of Also-Rans

As I have written before in several different places, the typical way comic book creators address the fraught histories of these non-white superhero characters is to either ignore their problematic origins and other stories as if they never happened or find ways to incorporate those problems in re-shaping that character. Both approaches have their problems. It is never a good idea to forget about those troubling racial notions and representations, because they never really go away. They just change in the context of contemporaneous racial ideas. Furthermore, even when seemingly erased, the ongoing nature of serialized comics and their changing creative and editorial teams means those elements of the stories can always come back and get re-incorporated in a later run. And in forcing characters to always have to address the racist ways they’ve been depicted and the stereotypes their behaviors once fulfilled, creators are severely limiting the kind of stories the characters can be a part of, and re-centering those problems as definitive for the character.

Like most Black superheroes of the 1970s, such as John Stewart (Green Lantern), Black Goliath, Black Lightning, the Falcon, and even Storm, Tyroc’s origins and characterization is indelibly connected to his Blackness in the form of cultural conflict and/or psychological doubt (at least he avoided having “Black” be a part of his superhero name). The arc of these characters tends towards either obscurity born out of solidarity with their communities or a liminal assimilation into the superhero mainstream that leaves room for race to return to the surface as a moral utility in the ideological reinforcement of liberal notions of tolerance. Tyroc is an exemplary figure of this arc because he both literally and figuratively returns to obscurity but not before being made to endure tests and challenges that work towards assimilating him by subjecting him to the Legion’s power in ways that both physically harm him (at one point in issue #218 he is nearly suffocated by Zoraz, for example) and publicly humiliate him (the ruse in issue #222).

A year after Tyroc’s first appearance, DC comics would have their first title featuring a black superhero, Black Lightning, whose focus was on a Metropolis ghetto where Superman is never seen—Suicide Slum. I have written a good deal about Black Lightning, including the recent CW show featuring the character, so I won’t spend too much time with him here, but it makes sense for a black superhero to focus on helping his own community, especially when that community goes ignored by other (all white) superheroes—a neglect that, as I explained in part one, cannot be excused away by the fact that they have not been written into the DC universe yet. Though the reasons for this neglect very often remain unspoken, it is difficult to not see that segregation as part of a larger pattern about what matters in the superhero universe (and thus our own). It is a classic double-bind that black characters are placed in. They can either focus on helping their own, which leaves them marginalized (and in the case of Black Lightning cancelled after 11 measly issues), or develop more of an audience through mostly ignoring their cultural or racial heritage and being written into a team book—their blackness serving the purpose of representing diversity through what is actually tokenism. As Black Lightning’s cachet grew, he moved further from his origins in Suicide Slum and his goals for that community—at least until that relationship was wholly re-imagined for the TV adaptation. Nevertheless, when depicted by non-Black writers, blackness —like the “black” in the hero’s name—mostly acts as if part of a superhero’s costume, serving for easy and broad identification.

Black Goliath’s inner-monologue: “As a bona-fide, grade A, all-American super-hero, you are one–big–joke!” (from Black Goliath #3 – June 1976)

Furthermore, the obscurity I mentioned above, while troubling, does not even guarantee that a Black character will remain safe from problematic treatment at the hands of white writers. Marvel’s Bill Foster aka Black Goliath (and other Hank Pym-discarded identities) had it even worse than being obscure. In the five issues of his hastily cancelled series, and in his guest appearances in other places afterwards, he is mostly depicted as an inept superhero who falls short of the ideas modeled by successful white heroes. This is a common feature of Black superheroes that I wrote about way back in 2014 in “Black Goliath: Some Black Super-Dude” and that I was reminded of when reading Legion of Super-Heroes #265. Before sending Shadowlass and Dawnstar back to Earth, Tyroc has a moment of doubt in himself that comes out of nowhere—like it is a requirement for him to touch on every cliché of the black superhero before he disappears forever.

Black Goliath would never really make it into the big time. He’d briefly be part of the Champions and later the West Coast Avengers. And eventually in 2006, after years of being an after-thought at best, he’d be served up as a sacrificial lamb to the altar of a summer crossover event, when he’d be killed by a clone of Thor during Mark Millar and Steve McNiven’s Civil War—the outrage of his heroic peers seeming out of proportion to his actual role in the comic universe. He’d then be replaced by his nephew, Tom Foster, in a move that stinks of the replaceability of under-developed Black characters.

Even more successful black superheroes are enmeshed in these narratives of assimilation or at the very least, prioritizing the values of a world that would dismiss them over their own. Luke Cage, aka Power Man, inhabited a marginal space in the Marvel Universe for a long time. Both his insistence on getting paid (his original title was Hero for Hire) and the fact that he operated out of an office in the seedy Times Square of 1970s New York City, marked him as different from the mainstream Marvel heroes. And when the Blaxploitation fad that spawned his character began to fade, Iron Fist was bumped into his book, so that he and the white kung-fu superhero could continue to limn the edge of a world dominated by Captain America and Iron Man, until cancelation in the early 80s. It would not be until the early 2000s, when he would be invited to join the New Avengers, that he’d make good. Brian Michael Bendis rehabilitated a literally and metaphorically ghettoized character to incorporate him into Marvel’s flagship line, disconnecting him from his roots.

Luke Cage explains his NYC mayor-inspired “Impact Super-Hero work.” (from New Avengers vol . 1 #17 – May 2006). [Click on image to see full page].

There is a notable scene early in that series that cements his journey from his seedy “for hire” world to the world of the Avengers. He convinces Captain America and his fellow Avengers to perform “impact superhero work,” emulating the NYPD policy of the Giuliani and Bloomberg eras, in which the saturation of a “bad neighborhood” with police ostensibly leads to a lowering of the local crime rate. In New Avengers #17 (2006)—written by Bendis with art by Mike Deodato Jr, Joe Pimentel, and Dave Stewart—Cage brings the team to what seems like a modern day Marzal, Detroit—ignoring the history of white flight and loss of industry in favor of a narrative of black criminality. Luke Cage agreed to join the Avengers if he could do some things his way and different from the status quo, but he is actually just recapitulating tactics that unfairly target marginalized people, while Iron Man and Captain America patronizingly approve of Cage’s articulate display when interviewed by the media. Cage points into the camera and issues his warning, “We’re coming to your neighborhood.” While the comic does not explicitly tell us whose neighborhoods he’s referring to, it is pretty clear he means other high crime areas inhabited by folks of color. The trick to this scene is that while it purportedly appears to let Cage have a say in what the Avengers pursue as superheroic policy, the policy itself—based on the NYPD’s “Project: Impact”—is a pernicious one that treats those communities as warzones, functions through racial profiling, leads to mass incarceration, and does not address the social and economic conditions that lead to high crime rates or redress the wrongs against those historically targeted by police. The scene serves to legitimate Luke Cage’s place in the Avengers and functions as an example of the Avengers doing good work, while never returning to this work again. Detroit might as well have phased out into another dimension like Marzal. In their token appearance and disappearance, such concerns recapitulate the values of their superheroic storyworlds.

I’d be lying if I said the earlier stories of Luke Cage weren’t problematic, with his hypermasculine Blaxploitation aesthetic often falling into the realm of cringe-inducing stereotype, especially in how his dialog was written, but at the same time, the fact that it was during his Avengers era that he officially dropped his use of the name Power Man—a not so oblique shortening of the too obvious Black Power Man—makes his transformation complete. Luckily, while short lived, the third volume of Power Man & Iron Fist (2016) by David Walker and Sanford Greene, returned Luke to his former community.

Of all well-known superhero comics, perhaps only Milestone’s heroes managed to re-imagine the superhero world as anything other than predominantly white. And if I haven’t written about them here, it is only because I am working through collecting many of the comics from that imprint which have not found their way into available collected editions. Milestone’s recently announced re-launch makes me cautiously optimistic that it represents greater interest in re-thinking superhero diversity and ideological values. To some degree, Lion Forge’s Catalyst Prime comics attempted a similar diverse approach, but its early momentum seems to have dwindled.

The world of superheroes remains unrepresentatively white and its characters must adhere to the confines of that culture. Black superheroes are twisted to alternately serve as stand-ins for all Black people or as the notable exception that achieves mainstream approval. They are propped up as strawmen for white liberal arguments or forced to disappear as to not upset the conservative tendencies of the status quo. Maybe Tyroc and the people of Marzal had the right of it to begin with, better to opt out and refuse to participate if being counted in the fraternity of superheroes means having to pretend that world has already achieved racial justice.

Pingback: May You Live In Interesting Times – This Week’s Links - Avada Classic Shop

Would the cancelled Vixen series from 1978 be relevant to this? Vixen would have been the first book starting a black woman at DC, but instead it ended up being the only “DC Explosion” book cancelled before even getting out one issue. That in and of itself is a sorry statement. Even so, the 1st issue was written and drawn before being shelved, and it was eventually released as fuzzy b&w photocopies in Cancelled Comics Cavalcade #2 The story is very reminiscent of Storm’s origin, and would have been solidly in keeping with the trends and problems you talk about in these articles.

More generally, what do you think of analyzing or considering unpublished/cancelled work when looking at trends at a publisher? Fair game? Or best left excluded?

LikeLiked by 1 person

First, thanks for commenting!

Second, I think the Vixen series (which I had never heard of) could definitely be evidence of how books featuring Black protagonists (Esp. at the time) were expected not to sell well, thus getting them lumped in with a bunch of other books that have other (non-racial) reasons for being considered of a lower tier. So while, we may not have a way of knowing that was the case with the Vixen series – it certainly fits the pattern of series like Black Lightning or Black Goliath (just more so because of Vixen’s intersecting marginal identities).

Third, in general I think that when relevant unpublished material can give us productive contexts for understanding or making claims about the primary text in question. Anything we can get our hands on is “fair game” as long as it is properly framed and explained.

Fourth, please come again!

LikeLike

Pingback: “Say It Loud!” Tyroc and the Trajectory of the Black Superhero (part 1) | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Legion of Super-Heroes: Before The Darkness | Comic Book Herald