n.b. Special thanks to Nathaniel “Hub” Hubbard—host of the Titan Up the Defense podcast—for providing invaluable research help on this essay, not all of which is immediately apparent and some of which I had to cut for room.

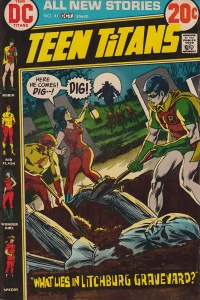

I had never heard of DC Comics’ Mal Duncan before a couple of years ago when the hosts of the Teen Titans Wasteland podcast—covering the entire original Teen Titans run of the 1960s and early 70s—made it to his first appearance in Teen Titans #26 (March-April 1970). Mal is DC Comics’ first black superhero, appearing over a year before the much better-known John Stewart would don the mantle of replacement Green Lantern (though not until after some failed attempts to convince the conservative DC Comics honchos that the time was right to introduce a black superhero). The podcast did a great job—in its typically hilarious and irreverent way—of informing listeners on Mal’s early appearances, the various problematic situations he was put into, troubling ways he was represented, and a handful of great moments of characterization, but when they got to Teen Titans #41 (October 1972), I immediately knew that I had to track it down and read it for myself. I wanted to write about it and finally scored a cheap copy last fall.

I had never heard of DC Comics’ Mal Duncan before a couple of years ago when the hosts of the Teen Titans Wasteland podcast—covering the entire original Teen Titans run of the 1960s and early 70s—made it to his first appearance in Teen Titans #26 (March-April 1970). Mal is DC Comics’ first black superhero, appearing over a year before the much better-known John Stewart would don the mantle of replacement Green Lantern (though not until after some failed attempts to convince the conservative DC Comics honchos that the time was right to introduce a black superhero). The podcast did a great job—in its typically hilarious and irreverent way—of informing listeners on Mal’s early appearances, the various problematic situations he was put into, troubling ways he was represented, and a handful of great moments of characterization, but when they got to Teen Titans #41 (October 1972), I immediately knew that I had to track it down and read it for myself. I wanted to write about it and finally scored a cheap copy last fall.

Mal joined the Teen Titans in a strange era when the adolescent superheroes were taken under the wing of Mr. Jupiter, the “richest man in the world,” after being reprimanded by their Justice League mentors for inadvertently causing the death of a world-famous philanthropist. As a result, they swore to stop using their powers or wearing their costumes, and adopted a pacifist approach to superheroing. Mal meets the team when they are sent by their new benefactor to survive “Hell’s Corner” a tough inner-city neighborhood with only a penny apiece. Menaced by a local street gang, Hell’s Hawks, the Titans are rescued by Mal, who ends up defeating the leader of the gang in a boxing match. Afterwards, he is invited to join the Teen Titans, but immediately feels inadequate (a trope common to narratives of Black superheroes of the 70s). As such, the issue ends with Mal boarding an experimental rocket to Venus in order to prove himself, requiring that his new teammates mount a rescue in the issue that follows. This sense of inadequacy would return repeatedly to define the character’s stint in Teen Titans and would be exacerbated by both his initial lack of powers and then the odd powers and gadgets writers would try to use to flesh out the character in the second run of the series (Teen Titans was cancelled for a little over three years between issues #43 and #44 before ending with issue #53).

Sometime between issue #26 and Teen Titans #41, however, the Teen Titans returned to their iconic uniforms, took to using their powers, and Robin rejoined the team (as he was off at college at the beginning of the Mr. Jupiter era). This return to the status quo makes Mal’s membership in the Titans even odder than it already was. He has neither powers, nor a superheroic identity at this point. It seems like what makes him “special” is his racial identity. His only “power” is the meta-power of tokenism to shape the stories involving the team and “What Lies in Litchburg Graveyard?” from the issue in question (#41) is perfect example of that.

Mr. Jupiter’s Aunt Hattie and the moojum doll.

Written by “Zany” Bob Haney with (gorgeous) art by Art Saaf and Nick Cardy, in this story Robin, Wonder Girl, Speedy and Mal accompany Mr. Jupiter to his familial estate to visit his venerable Aunt Hattie who is on her deathbed. It turns out that Hattie is not Jupiter’s biological aunt, but the woman that raised him after his parents died at a young age. Mal expresses surprise when he sees that Hattie is black. “Huh? She’s your…aunt — ? But…But…she…she’s…a soul sister!?” (damn, but white writers—especially of the time—are terrible at the nuances of African-American Vernacular English!). Jupiter explains that Hattie is over 100 years old and was an escaped slave who arrived on his family estate with her father, fleeing their slavemaster Captain Ahab Barstow. As Jupiter and the Titans gather around Hattie’s bed, the old woman mutters “Moojum!” and we see her story play out as a dream that flashes back to her escape from bondage as a young girl. Chased down by Barstow, Hattie’s father has the girl hide and then in a second flashback to before their escape we see her receiving a straw “moojum doll” from Mose, a “half-Indian shaman” who explains “…if you meet trouble, the moojum doll will help you!” The dream ends with young Hattie calling on the doll to aid her father who is trapped by Barstow’s dogs upon a frozen river (clearly a reference to Eliza’s flight to freedom across the frozen Ohio River in Uncle Tom’s Cabin), though we don’t get to see how the doll might exactly perform that rescue. Aunt Hattie awakens just long enough to hand the old straw moojum doll—which she’d been clutching—to Mal, explaining that he will need it. He doesn’t want to take it, but Mr. Jupiter insists. Hattie then dies. At her burial, Mal puts the doll atop her casket.

The doll, of course, becomes important to the story—some kind of sloppy mash-up between a voodoo doll and Hopi kachina figures—but what interests me about this Teen Titans comic are three elements: the power of the racial identity of token characters to shape stories in a meta-narrative sense, the tension between the ostensibly anti-racist sentiment and the causal dismissal of black experiences in those stories, and the difference in what’s at stake for characters and readers (depending upon their racial identity) in stories revolving around racial legacies and discrimination through a re-framing I call “white memory.”

But, before I move on to those three elements, it’s important to take a look at how the story’s set-up, described above, serves as a warning for the insensitivity to expect from the rest of it.

First of all, the sloppy writing for the story means that despite having been raised by this black woman—who is quite literally his “mammy”—Mr. Jupiter has not cared enough about her to have visited her in 30 years! And, apparently despite being a centenarian nearing her death, the Teen Titans and their benefactor find her living in a mansion all by herself. Did he not pay for her to have a home aid? A nurse? Did she have no friends? No other family? Of course, we can dismiss this stuff as details unimportant to a superhero story that is part of a series often notable for its silliness (Haney didn’t earn the sobriquet “Zany” for no reason), but nevertheless these missing details makes Hattie seem like a superfluous part of this rich white man’s life. She seems more like a loyal servant and property caretaker than a member of the family, no matter what Jupiter claims. Hub and Corey—hosts of Teen Titans Wasteland— in their episode covering Teen Titans #41, do a good job of exploring the many elements of story, in addition to these, that just make no damn sense narratively

Secondly, when Mal expresses his surprise that Aunt Hattie is a “soul sister,” Mr. Jupiter responds in a way that demonstrates the quintessential ideal of interracial relationships as it was imagined in early 1970s America and that continues to be the norm through to the current era—so-called “colorblindness.” “Yes, Mal, she’s Black! I never thought to tell you!” It is clear that we as readers are meant to admire Mr. Jupiter’s lack of consideration of her race as important. The story’s introduction of the character, however, just makes me wonder why, if she was really so important and influential to the man, he hadn’t mentioned her before this moment. And, in the context of talking about her, her race and specific history might have come up. Instead, this interaction only reinforces the irksome and tiring canard that paints a person of color as the rude one for being so concerned with racial identity as to point it out, while portraying the white character as virtuous for ignoring it. (For other examples—this time from the 1980s—consider the exchange between J. Jonah Jameson and an Al Sharpton stand-in I reference in “Super-Hegemonic Team-Up: Spider-Man, Daredevil & “The Death of Jean DeWolfe” and the conversation between James Rhodes/Iron Man and Reed Richards in Secret Wars #8). This “race-neutral” attitude permeates this story not only through its events, but through its framing. For example, the narration introducing the dream sequence flashback describes the Antebellum slavery-focused story as being about “man’s inhumanity to man,” universalizing what is a clearly racialized subject. Even the cover to the issue literally erases Mal from a story that revolves around him. The other white Teen Titans are depicted in peril, when none of them are actually endangered at any point in the story—only Mal is ever in danger, and specifically because he is black.

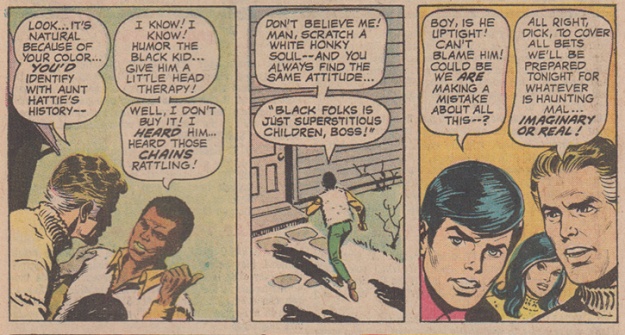

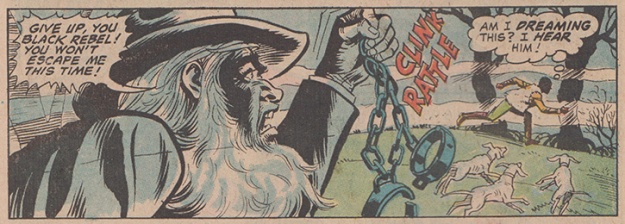

The rest of the story after Aunt Haddie’s funeral perfectly exemplifies the sloppy writing and erasure of specificity that ultimately come out in favor of white supremacist status quo even when presenting a story ostensibly sympathetic to Black Americans. The night after the funeral Mal notices “a freaky dude and some nasty hounds” out on the iced over river nearby, but when he goes to get a better look from another window, the apparition is gone. When Mr. Jupiter is told about the vision the next morning, he suggests it was just the teen’s imagination, sparked by the tale of Hattie’s escape, dismissing Mal’s experience despite the existence of ghosts and other supernatural occurrences being common not only to the DC Universe, but to the very pages of Teen Titans. Later that afternoon when Mal is out hiking, he once again hears the dogs howling and turns to find the ghost of Captain Barstow and his dogs pursuing him. Locked out of the house, he smashes through a window into its safety. When he looks back the ghost is gone. Once again Jupiter’s white skepticism is not satisfied with Mal’s report of what happened. He points to the fact that there are no tracks on the ground where the black teen said it happened. Despite Mal explaining that the earth being frozen means there’d be no tracks, Jupiter leaps to a different conclusion: “Look…it’s only natural because of your color you’d identify with Aunt Hattie’s history–.” Of course, what contributes to Mal’s anxiety (aside from the literal ghost of a slave-catcher) is not his “color,” but the reality of history manifesting as this ghostly metaphor and targeting him for his race. But according to Jupiter, it is all in Mal’s mind.

Mr. Jupiter dismisses Mal’s experience. Mal tells it like it is about honkies. Robin tries to use his privilege to help others, but still sounds condescending while doing it.

The tension here is fascinating, because while the story presents a rather insensitive portrayal of historical-trauma-made-manifest, it makes legible the dominant culture’s not uncommon dismissal of both the experiences of marginalized people and the ways the present is contingent on the past. This dismissal, in turn, recapitulates and reifies the very experiences being denied as to become an example of it. It is impossible to know what Bob Haney intended in having Mr. Jupiter deny Mal’s experience and relating it directly to his race in a way that undermines its legitimacy, rather than bolster it. Mal’s response, however, is simultaneously heartbreaking and refreshingly real. He follows up his repeated assertion that he knows what he experienced by stomping away saying, “Don’t believe me! Man, scratch a honky soul — and your always find the same attitude…” In other words, despite Jupiter’s ostensible sensitivity to issues of race, his actual behavior belies that and Mal is aware of this tendency in white liberals. Mal then adds a sarcastic comment voicing the obsequiousness his experience tells him that white people want from Black folks, “Black folks is just superstitious children, boss!”

Part of what makes the story heart-wrenching is that Mal is so alone and isolated in this experience, being the token black Titan. Not only is he not believed by Mr. Jupiter, but none of his teammates really have his back. Robin, who is dismissive of Mal’s bad vibes about the place from the opening page, even refers to him as “uptight” even as he tries to give Mal the benefit of the doubt. But when the (white) Boy Wonder asks Mr. Jupiter if they might be wrong to not believe Mal only then is the billionaire convinced to look into “whatever is haunting Mal…imaginary or real!” So, just so it’s clear, twice Mal explains his experience to his teammates and mentor to no avail, but Robin, a white kid with a rich daddy, wonders aloud just once and Jupiter decides to humor him and look into it.

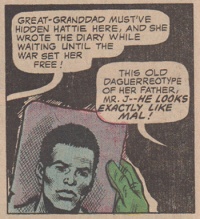

Both the sorrow and the promise of “What Lies in Litchfield Graveyard?” emerge from how the story robs Mal of any agency. The merits of his experience are disbelieved and there is nothing he can physically do to escape the ghost or fight it. That night Mal awakens from a dream in which he is in shackles like a slave to find himself in a real shackle and being pulled out the window by the ghost of Captain Barstow. He is freed thanks to Mr. Jupiter’s sharpshooting abilities—now ready for trouble since Robin suggested it—breaking the chain that holds Mal with an old rifle. Powerless against the incorporeal threat, all Mal can do is run. He ducks into an old shed and falls through the rotted floor into secret tunnels beneath the estate. It seems that in the DC Universe the Underground Railroad was really underground. As the ghost dogs are still on his heels, Mal continues to run, making his way out of the tunnel through a cave entrance down by the river. Soon, the rest of the team and Mr. Jupiter discover the tunnel as well, and in their own pursuit they discover a diary and daguerreotype that had belonged to Hattie when she was hidden down there by Jupiter’s great-grandfather until the Civil War was over. The photo is of Hattie’s father—Ned Jackson. Why would an escaping slave have (or bother to bring) a portrait of himself on his flight north? The only real answer is a meta one: to explain why Captain Barstow has reappeared in ghost form after over 100 years and is so desperate to capture Mal. Mal Duncan looks just like Hattie’s dad!

Such a coincidence is typical of comic book narratives and plenty of other adventure stories, farces, and folktales: heretofore unknown lookalikes lead to various kinds of hijinks and confusion. In this case, however, all the look-alike plot allows the comic to do is deny racial profiling: no one ever has to speak the words, “This ghost is after you because you are Black.” In the context of the genre and the underrepresentation of Black characters and their stories this coincidence is not only a too obvious narrative weakness, it threatens to recall the “They all look alike” stereotype and reinforce the interchangeability of Black characters common to stories that imagine any individual Black character as a stand in for any or all Black people. I wrote a bit about the indistinguishability of Black characters in superhero comics in “Marvel Five-in-One: Prominent, Notorious and Invisible Black Lives of the Marvel Universe” back in May of 2016, but “What Lies in Litchburgh Graveyard?” provides a more prominent example of how this indistinguishability is leveraged for use in a narrative aimed towards white readers. Indistinguishability is a privilege afforded to white characters in “twin” narratives ranging from Shakespeare’s “A Comedy of Errors” to Disney’s The Parent Trap. At their most fanciful they are played for farcical humor, an opportunity for infidelity and reuniting families, or, like in the case of Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper, to reveal class-based injustice. But for Black characters and other PoC, indistinguishability represents a danger stemming from lack of control over the roles they are placed into by the white gaze. To use such a trope in a setting like the DC Universe of the early 1970s that has such a profound lack of Black characters is to not think through the connotations of such a story for those characters. Even across a century’s worth of time, Mal still fits the profile of a runaway slave, but the twist of plot allows for deniability of the fact.

The found diary reveals what happened after the earlier dream sequence left off. Back in the 19th century, at young Hattie’s behest, the magical moojum doll came to life, grew to gigantic size and drowned Barstow and his hounds in the icy river. Trapped out on the ice like Hattie’s father a hundred years before, Mal is about to meet a grisly fate—“a life of eternal toil”—when the now giant moojum doll appears to once again save the day. Robin and Mr. Jupiter, remembering that Mal threw the doll atop Hattie’s casket dug up the grave and implored the doll’s aid, as nothing any of the Titans could do had any effect against the ghostly figures. It turns out that being “killed” in the same way that the original mortal form was killed is how one defeats a ghost. The straw doll-turned-goliath drags the slave-catcher and his dogs under the icy river reenacting their drowning and ending the danger they pose. Mal plays no role in his own rescue, and in fact, made it more difficult by burying the moojum doll.

All is well, but guess what? Perhaps unsurprisingly, Mr. Jupiter never apologizes for doubting Mal, and in the euphoria of being saved, I guess, Mal forgets to make an issue of it. He just thanks Jupiter and the others for their help. His justified anger giving way to the narrative’s requirement to resolve any racial animus, even if it means just making the black character forget about it. (It’s what white America wants black people and other PoC to do about any of their grievances: forget it for the sake of getting along.)

This comic book is not really interested in what the context for the story signifies. Instead, Mal’s role as a token character provides the predominantly white comic access to a race-inflected story. Yet it also provides a way to put his treatment—by both within the narrative and by the writer—into relief as an artifact of the necessity to downplay the specific role of white supremacy in maintaining racial hierarchies in America. It is a model of the absurd lengths some will go to maintain deniability.

One way in which those racial hierarchies are made visible is through Mr, Jupiter’s attitude and Mal’s discomfort. They reinforce the degree to which slavery as a motif in a story has very different stakes not only for black versus white characters, but for potential readers. The story’s attempt to universalize slavery as “man’s inhumanity to man” obscures not only the specific history of chattel slavery in America but also the way in which that historical trauma impacts people through its relation to the present. In other words, white, wealthy, and privileged Mr. Jupiter can easily dismiss what literally haunts both Mal Duncan and America. Similarly, white readers can easily dismiss this as just another ghost story.

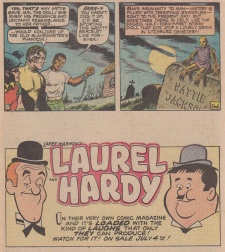

The house ad beneath the final panels helps demonstrate how white memory creates a necessary detachment from the consequences of history. [Click image to see larger version]

And if the story itself were not enough to reinforce that difference in what slavery can mean, the paratextual elements in the half page beneath the story’s final panels—one of which depicts the Moojum doll standing guard atop Hattie’s gravestone—reminds us of how quickly some can move on: an ad for a Laurel and Hardy comic book “loaded with the kind of laughs only they can produce.” The impact of slavery as anything more than a narrative trope is diffused by the final panel’s echoing the universalizing introduction of Hattie’s story. Slavery’s specific racialized influence on American society becomes genericized and thus impersonal. The easy turn to Laurel and Hardy demonstrates the degree to which diffusion of responsibility allows detachment from that ongoing influence. It is a perfect example of how white cultural memory functions to transform historical events tied to the dominant culture victimizing the marginalized and vulnerable into generic evils rather than historically contingent ones with consequences reaching into the present moment. I don’t mean to overstate the value of “What Lies in Litchberg Graveyard?” by comparing it to Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1978), but the role of memory and the ghost of slavery’s past brings the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel to mind.

Beloved (which I am in the middle of re-reading for the first time in about 15 years)—at the risk of reducing a rich and complex novel—explores the psychological legacy of slavery through Sethe, who was forced to kill her two year-old daughter to keep her from being taken back to bondage after having escaped to Ohio in 1856. Nearly twenty years later, her household is haunted by what she is convinced is the spirit of her dead daughter, who later takes the physical form of Beloved, a young woman who comes to dominate Sethe’s life in unhealthy ways. In “Of Slaves and Other Swamp Things: Black Southern History as Comic Book Horror” from Comics and the U.S. South, Qiana Whitted puts Morrison’s novel in conversation with Alan Moore and Stephen Bissette’s “Southern Change” and “Strange Fruit” from Saga of the Swamp Thing #41 and #42 through the concept of “rememory,” which Morrison develops in the novel. Whitted explains that “rememory” is “useful in framing an experiential understanding of the present as being physically and psychologically inscribed with traces of the past” (188). It would not be hard to read the ghost of Barstow and his dogs as a manifestation of the psychological wages of slavery tied to a place that demarked the liminality between freedom and bondage. Beloved complicates the idea of freedom by making the physical and psychological bonds of slavery manifest 20 years on. Similarly, one hundred years removed from emancipation and Teen Titans #41 provides a site for considering how Mal is still bound by attitudes and ideas stemming from the legacy of slavery in America.

Of course, Barstow and his dogs are quite literally a cartoon version of the much more complex set of emotions and experiences explored in Morrison’s book. There is nothing in this comic that matches the intensity and incomprehensible toll of Sethe’s experience of having to kill her own child rather than have her returned to bondage, but there is nevertheless a suggestion of what bondage can drive a person to do and how the evil of enslavement can act through the body of the enslaved even when in the form of a loving act meant to resist a life of captivity. Ned Jackson has to leave his daughter, Hattie, behind and presumably never returns to look for her. The comic suggests that he left her for her sake—to increase her chance of escape by drawing any further pursuit away from the Jupiter estate. This choice may not be as visceral and profound as that Sethe makes, but Ned Jackson’s choice does end up binding Hattie to that land and in servitude to a white family. The very notion of freedom is problematized in this way. It is an ironic fate that Mal recapitulates via his fealty to Mr. Jupiter’s Teen Titans project (leaving his never-mentioned family behind in the ghetto). In other words, the “evil ghosts” that continue to influence American society’s relationship with race may not always take the form of the caricature slave-master and his dogs, but some like Beloved, take the form of something that can be mistaken for love—in this case, the patronage of a wealthy white family. The story does not do enough to make a connection between the discomforting relationship of a black ex-slave made servant to such a family, raising their children, while apparently having no children of her own or life outside of that position. Even for Mr. Jupiter to refer to Hattie as “family” is not evidence of her freedom or equality. Given how commonplace referring to slaves as “family” was in the antebellum American South, it’d be easy for a white family north of the Mason-Dixon to think that way about a ward.

Mal awakens from a dream to find his vision of the past is quite literally chained to his present and possible future.

Taken together, the various elements of “What Lies in Litchburg Graveyard?” elucidated here demonstrate the flipside of Morrison’s “rememory,” “white memory,” a denial of those “physically and psychologically inscribed with traces of the past” in issues of race, even in the face of the testimony of black people and often in the face of other direct evidence. The framing of the story through such a white gaze functions as a complex form of erasure that leaves references to historical events but obscures causality as to retain a form of cultural innocence. In Teen Titans #41, traumatic events that in Whitted’s words, “endure with an affective potency that can be perceived by others” are robbed of their “emotional resonances” through a recourse to white memory, which ignores Aunt Hattie until her death brings narrative consequences, discounts Mal’s sense of reality, and allows for Mr. Jupiter’s behavior towards Mal to be immediately forgotten at story’s end. The ghost of Captain Bartsow may have been defeated, but the ghost of countless well-meaning Mr. Jupiters continues to gaslight whole swaths of American society whose experiences are decidedly different.

In the end, Beloved finds its resolution in a community of black women who come together to help Sethe exorcise the spirit of slavery’s legacy and her own guilt, giving the tragic tale a sense of promise, even as it reminds us of Faulkner’s invocation that “the past is never dead.” But, in “What Lies in Litchburg Graveyard?” Mal’s token blackness subjects him alone to this memory come to life. The token identity used to make the narrative available to a Teen Titans comic book isolates him from a community through which to productively process the affective consequences of slavery’s specter.

As I have read more and more black superheroes’ introductions and key stories of the 70s and 80s, it can start to feel like they are all tragic figures, even when not intended to be cast that way. Mal is the forgotten Titan. When it comes to race and the Teen Titans, Cyborg is the most well-known Black character who is short-changed by the limits of the genre to engage with the intersection of blackness and other vectors of identity. As Robert Jones Jr famously reminds us in “Humanity Not Included: DC’s Cyborg and the Mechanization of the Black Body,” Cyborg is written to play an active part in his own abjection. Mal, on the other hand, provides a new place to examine race in superhero comics. Even the handful of scholarly books that specifically examine black superheroes or black comics more broadly—like Super Black: American Pop Culture and Black Superheroes (2011) or The Blacker the Ink: Constructions of Black Identity in Comics & Sequential Art (2015)—do not even mention Mal Duncan in passing. I think his very obscurity is a model for thinking about tokenism, not just as a narrow representation of difference, but as an influence on the shape of those stories for mainstream consumption. As I hope this essay has suggested, this influence not only allows white characters access to race-inflected stories without the requisite responsibility for thinking through their contexts and connotations, but in retrospect allow readers an opportunity to see an unguarded representation of normalized paternalistic attitudes towards black people presented as positive. This latter opportunity, however, also gives a guide for places where “rememory” engages with the recent past (I am using the fact that Teen Titans #41 was published in my lifetime to define “recent”). It creates a thread from our present moment to these liminal phases of “racial progress” in the 1960s and 70s and back to shared historical tragedy of slavery that reinforces what Whitted calls the “cultural scripts” (195) of racial hierarchy that recycle relationships of community and place even as social conditions change. Even in the effort to be more inclusive and tell what seem like new stories, we need to be alert to how these “scripts” can still shape such stories and erase the very people and voices they are meant to include.

Pingback: “I AM (not) FROM BEYOND!” – Situating Scholarship & the Writing “I” | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: “Say It Loud!” Tyroc and the Trajectory of the Black Superhero (part 1) | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: That Time the Teen Titans Totally Joined a Weird Cult – Book Library

Pingback: That Time the Teen Titans Totally Joined a Weird Cult « My Life As Prose

Pingback: Year-End Meta 2022: “Escaping Total Nullification” | The Middle Spaces