n.b. In order to be as clear as possible, I have chosen in this piece on Hazel Newlevant’s memoir to use their last name when referring to them as an author/artist, and as “Hazel” when referring to them as a “character” in the narrative.

I was lucky to get to read a preview chapter of Hazel Newlevant’s graphic memoir, No Ivy League, back in the summer of 2018. Newlevant was a guest artist at the Comics Studies Society’s Mind the Gaps conference and between the preview and how they spoke about the project I was drawn to it. I could not wait for the full release, which I pre-ordered. When it arrived at the end of this past summer, I dug into it immediately.

The memoir covers a summer when teen Newlevant was trying to raise money for a trip to see Guster. In addition to taking a job helping to free a portion of Forest Park from English Ivy (an invasive species that chokes out native trees), Hazel and friends, all home-schooled, enter a contest to make a video extolling the virtues of homeschooling. The grand prize is $1000, and they agree to split it evenly no matter who wins. Working in the “No Ivy League” (where the book gets its title), Hazel gets to spend time with public school kids, something they are not accustomed to, and soon finds out that the summer work program was really designed for so-called “at-risk” youth, a characterization that does not apply to Hazel, what with their “hippie-style” homeschooled white middle-class upbringing. This leads to the scene that sold me on the book when I read the preview: a very earnest Hazel asking a black co-worker who his favorite rappers are after having just met him. It is one of those scenes where a well-meaning white person is trying to connect cross-racially by bringing up what they think shows they are down and progressive but that nevertheless has a problematic assumption about what defines black culture and identity. It is this kind of cluelessness that the graphic memoir is really trying to interrogate, a cluelessness that the book suggests has its origins not only in the particular bubble of their upbringing, but that is tied to Oregon’s history as a bastion for white supremacist ideas and racial homogeneity.

No Ivy League does its best to connect interpersonal relationships across race, class, and gender with historical social and political forces that undergird how those relations play out. It also touches on the misleading conclusions that individuals can come to in part due to an erasure of that connection and its recursivity. What I mean by recursivity is that institutionalized historical oppressions shape individual relationships and racialized conflicts, but those relations and conflicts also shape how people see or understand (or don’t see or understand) those institutional forces, which in turn affects our ability to address them. (This is something that class-first anti-identarian people on the Left can’t seem to grasp).

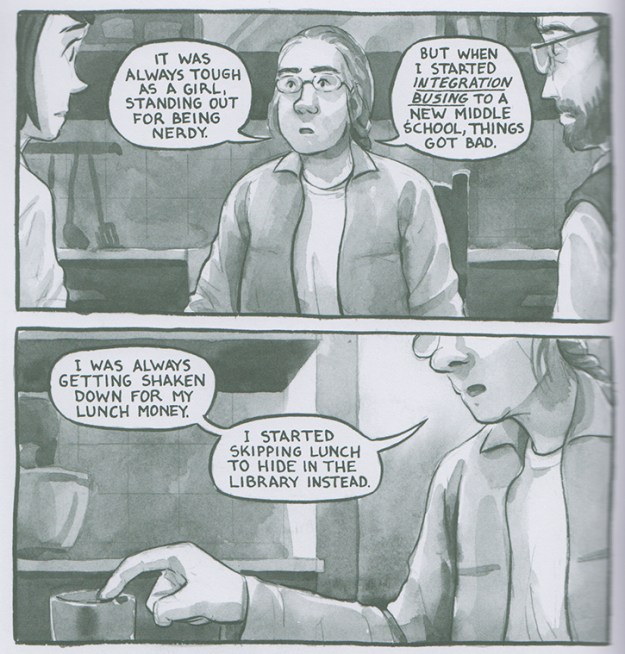

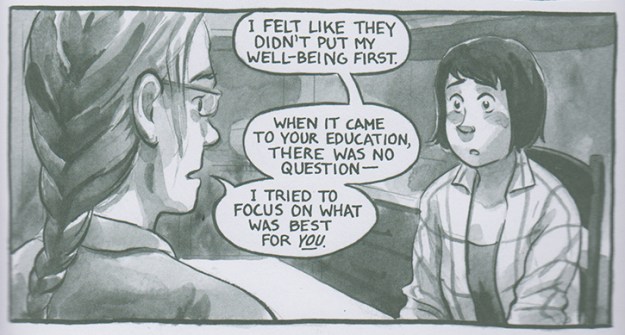

Hazel’s awkward interactions with black kids at their job are juxtaposed with the eventual discovery that their homeschooling was a result of their mother’s experience with busing. As one of the few white kids in a predominantly black school, she was bullied and felt ostracized—an unfortunate, albeit temporary—reversal of broader social conditions. Hazel is horrified by the implications of their mother’s casual admission that “When it came to [Hazel’s] education there was no question, [she] tried to focus on what was best for [her child]” (155). It may be said so often as to be cliché, but the double-edged significance of “the personal is political” is made explicit by this fact of the story. In this case, Newlevant’s mom chose what she imagined was her child’s best interest over an effort towards broader social progress because of her personal experience. This personal choice may seem just that, personal, but it also tacitly supports segregation by assuming both that black students will always bully white kids and that her child’s experience and reaction to it would be the same as it had been in the 1960s (I am guessing here at the mother’s age, it could have been a decade earlier or later, I guess). This is a difficult legacy to accept and live with, one that Newlevant connects in the memoir to the difference in consequences for the behaviors of young white and black people for perceived violations of social and legal frameworks that shape American life, differences that can also vary based on who the perceived target of those violations might be.

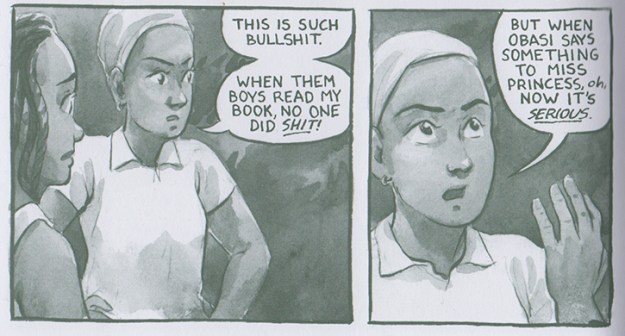

For example, Obasi, a black male co-worker uses the fact that 17-year old Hazel’s boyfriend is only 15 to “jokingly” ask that since he is 15 too, if Hazel would suck his dick. Soon after reporting the incident to their supervisors, Hazel feels even worse, alienated from their peers for being a “snitch” who needs “thicker skin” and guilty because Obasi loses his job. It is in the course of explaining the situation to their parents that Hazel finds out about the real reason behind being homeschooled. Similarly, it is in reporting the harassing remarks to their supervisor that they learn that the rest of the “No Ivy League” are “at-risk” youth, while Hazel was hired for seeming “earnest.” Thus, though never explicitly explained, I think it is a safe assumption that that difference in criteria equates with a difference in expectations. This difference shapes how the encounter is handled by those in-charge who explicitly suggest they thought Hazel would be “a good influence on the crew.” The inconsistent consequences for Obasi are made clear, when another Black co-worker, Kelsey, complains aloud that when a group of non-black young male co-workers found her steamy “street-lit” novel, reading aloud from it, mocking her and saying some inappropriate stuff in the process, they were not disciplined but just told to get back to work. But, as Kelsey points out, when “Obasi says something to Miss Princess [Hazel]…it’s serious.” When she adds the rhetorical question, “Wonder why that could be?” everyone knows the implied answer.

Hazels co-worker, Kelsey, complains about the inconsistent consequences for harassment on the “No Ivy League” squad.

But as Jazmine Joyner points out in her review of No Ivy League, “The story isn’t confronting the issues it presents. No Ivy League states these new ideas and experiences Hazel is going through, but leaves the hard stuff for the reader to deal with.” Which is to say, that while the YA graphic novel does a great job of evoking the feelings a young Newlevant experiences—the guilt, the confusion, the sense of dreadful discovery as she goes to the public library to read about Oregon’s origins as a specifically whites-only space—there is no confrontation with these realities in those experiences. The inequalities of the workplace and the difference in how harassment is addressed (if at all) are never discussed among the characters. The complicity in attitudes and beliefs that condone segregation and their role in Newlevant’s education are never confronted. We never see Hazel ask their mom for more details about that choice. Instead, we are left with the idea that their mom does not regret the decision at all.

Of course, as a memoir, readers must accept that within the scope of the story, Hazel may just not have been ready for those confrontations at that age, and that the scope of the historical injustices we see play out interpersonally is just too much for one 17-year old kid to do anything about in a way that will ring true in the end. Instead, the weak reconciliation we see between Hazel and their co-worker Aisha (who is also Obasi’s cousin)—grooving together to music at the end-of-the-summer job party after patching over the race and class tensions in their relationship—might be the best we can hope for, even if it feels unsatisfactory both politically and narratively. That said, however, this might have been mitigated with some reflection, with a voice outside the narrative looking back and framing these realistic disappointments and shortcomings as to make their significance explicitly part of a broader discourse. Without that, as Joyner makes clear in her review, No Ivy League comes off as a book that is aimed at a white audience. I don’t think that needs to be the case. The book can be more properly framed if taught in a class (something I don’t doubt will happen) but read on its own it feels like it relies so heavily on the personal connection that it unintentionally tries to erase the broader social conditions it reveals. It’s unclear to me yet if this failure to erase them is a success of the memoir or just a result of the profundity of what is revealed on both personal and social levels.

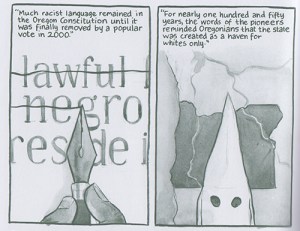

The fountain pen and the klan hood create a visual echo that suggests the different ways white supremacy is enacted and maintained.

It may be too easy to suggest this, but in reading and re-reading No Ivy League, I could not help but feel that a better ending would have had Hazel expressing continued confusion to go along with the feel-good scene of happily dancing with Aisha and other co-workers. If it could have found some way to more explicitly cast light on the multiple overlapping stories present in this place, time, and among these people—even if the memoir as a genre and stand-alone comic as a format could not actually tell us all those stories—it might have been more successful. Hazel does begin to ask questions about race and the political connotations of homeschooling, which would seem too pat if answered. Yet No Ivy League is still in danger of making that final work party appear like an answer—”we can be friends despite my inadvertent role in maintaining racial injustice”—even though I don’t think Newlevant wants it to come off that way.

Still Newlevant’s gorgeous art in No Ivy League does at times provide insight that connects their individual search for answers about the place they live to the social forces that shaped their mother’s experiences and thus attitude. This is particularly well done in depicting that research. For example, a diptych of panels shows a fountain pen expunging racist language from Oregon’s state constitution echoing the shape of a Klan hood, evoking the different ways white supremacy is reinforced. Something that is really impressive about Newlevant’s art—aside from a rounded cartoony style that excels at conveying facial expressions and body language—is their use of a green wash watercolor style. The range of what these various shades can convey is outstandingly rendered and connects everything with a visual motif that echoes the very forest Hazel is working in and the choking network of colonizing vines to cut through.

Reading No Ivy League also cast my mind to Jonathan Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude (2003). This is probably not a surprise to anyone who knows me or follows my work. The Fortress of Solitude is one of my all-time favorite books. I have written about it at length, including a chapter in my dissertation dedicated to how it puts comics, music, and place to work to build positional identities in a way that demonstrates what I have coined “(re)collection.” The specific setting for the novel—1970s Brooklyn—is significantly different from that of No Ivy League. Yet, The Fortress of Solitude’s exploration of gentrification through the figure of young Dylan Ebdus as a kind of unwilling wedge that helps make room for a much transformed Brooklyn of the late 90s and early 2000s, also highlights the use of children as tools in reinforcing white supremacy (even if unintentionally). Putting No Ivy League in conversation with Lethem’s novel really helps to make that insidiousness clear and highlight its ability to reinforce its ideology even through those who claim to be explicitly against it.

Reading No Ivy League also cast my mind to Jonathan Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude (2003). This is probably not a surprise to anyone who knows me or follows my work. The Fortress of Solitude is one of my all-time favorite books. I have written about it at length, including a chapter in my dissertation dedicated to how it puts comics, music, and place to work to build positional identities in a way that demonstrates what I have coined “(re)collection.” The specific setting for the novel—1970s Brooklyn—is significantly different from that of No Ivy League. Yet, The Fortress of Solitude’s exploration of gentrification through the figure of young Dylan Ebdus as a kind of unwilling wedge that helps make room for a much transformed Brooklyn of the late 90s and early 2000s, also highlights the use of children as tools in reinforcing white supremacy (even if unintentionally). Putting No Ivy League in conversation with Lethem’s novel really helps to make that insidiousness clear and highlight its ability to reinforce its ideology even through those who claim to be explicitly against it.

In one scene early in the novel, Dylan’s mom, Rachel Ebdus, is having a conversation with a neighbor, Isabel Vendle, an elderly local developer who has watched with much chagrin as her neighborhood has become home to black and brown families, as white people moved away. As an indication of Vendle’s outlook about her community (or rather those she cannot accept as an actual part of that community), she refers to the Latinx men on the block as the “undershirts” (8), connecting their class position and ethnicity through a dismissive synecdoche. She has a plan to reverse white flight, and Lethem even ascribes to her the actions of an actual historical person similar to her—Helen Buckler—who according to historian Suleiman Osman quite explicitly sought to change the character of the neighborhood by renaming it Boerum Hill (341). As Lethem writes,

Gowanus wouldn’t do, Gowanus was a canal and a housing project. Isabel Vendle needed to distinguish her encampment from the Gowanus Houses, from Wyckoff Gardens, that other housing project which hemmed in her new paradise, distinguish it from the canal, from Red Hook, Flatbush, from downtown Brooklyn, where the Brooklyn House of Detention loomed… She was explicating a link to the Heights, the Slope. So, Boerum Hill, though there wasn’t any hill. (7)

While ostensibly discussing Dylan’s schooling—Rachel insists he will go to the local public school, Vendel expressing some implicit white racial solidarity by bringing up the possibility of financial aid for the boy to go to area private schools— the women’s disagreement about what is best for Dylan personifies the urge to define the neighborhood and shape its character through two equally problematic approaches to race.

Vendle’s point of view on gentrification is explicitly racist, an attempt—as Matt Godbey writes in “Gentrification, Authenticity and White Middle-Class Identity in Jonathan Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude” —to forge a “habitat that [is] safe and suitable for affluent white residents” (138). While the point of view readers can ascribe to Newlevant’s mother in No Ivy League is not necessarily, explicitly racist, it has the same ultimate goal in mind—ensuring her child a “safe and suitable” environment. The fact that she is making this choice for her own child and based on her experiences, however, could obscure the racial basis for that choice. And yet, Rachel is an example of how knowledge of and sympathy for those broader social inequities is no protection against perpetuating problematic attitudes. Yes, we expect someone like Isabel Vendle to say of Dylan going to P.S. 38 with brown and black kids, “He’ll be with children who’ll never learn,” but when Rachel responds with “Maybe he’ll teach them” (an echo of the “good influence” Hazel’s supervisors mention), she not only tacitly accepts that her white child is better and smarter than those kids of color, but that somehow the presence of a white face is going to correct systemic inequality and oppression for those children. Rachel further compounds the problem by generalizing from her experience as a “Brooklyn street kid” (13) claiming that “It’s a problem for him to solve, school. I did it, so can he” (20). This is a “problem” that affluent white families in New York City continue to try to solve by resisting efforts to diversify public schools, (and that remains an issue throughout the U.S.) but Rachel’s “they’ll figure it out” approach is hardly much better.

So here we have two mothers coming to opposite decisions about sending their kids to public school and the racialized conflict they may have to deal with, but neither is considering the scope outside of the personal. Newlevant’s mom makes her decision based on her experience of “getting shaken down for…lunch money,” “skipping lunch to hide in the library,” and feeling like adults did not put her “well-being first.” Rachel Ebdus sees her ability to endure and even thrive as a white girl in Brooklyn public school as evidence that her son can not only do the same but make it somehow better for the poor black and brown kids. Despite her assertion that “Boerum Hill is pretentious bullshit” (52), she is still complicit in reframing the neighborhood to fit her own conception of what Brooklyn is supposed to be like according to her own upbringing, ignoring the particularities of the racial context that makes that historical moment different from her own childhood experience—an experience that we can imagine has more in common with the idealized ethnic enclaves of Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (set in Williamsburg, where Rachel grew up), than the “weird patchwork [of] middle class, welfare class, black, Hispanic…an early wave of gentrifying whites, housing projects and historically landmarked brownstones” (99-100) that made up the blocks in and around Gowanus according to Osman’s The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn (2010). Of course, we have very little knowledge of what Rachel’s young life was like, but we do know a lot about Dylan’s: being sure to carry extra change as an offering to the young Black men who’d hit him up for money and hoping to evade the indignity of “the yoke.”

Hazel’s mother explaining the bullying she experienced from Black students when she was bused to a new school.

I wrote about the practice of “yoking” in a paper I presented at the Forces at Play: Body, Space & Power Conference at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst back in 2012. “The Yoke’s On You: Mugging as Cultural Practice in Jonathan Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude” argues that yoking in the novel is “a manifestation of the power dynamics of gentrification played out through the bodies of young men” and a complex site of play that “[f]or Dylan Ebdus…is an indication that the narrative of progressive integration instilled in him by his mother is obfuscating a racial reality that he must physically confront.” Yoking is difficult to define, and when I presented the paper I mentioned above, I actually convinced one of my fellow presenters to help me demonstrate its awkward dance. Perhaps it is best to use Lethem’s own words to explain it:

[T]he yoke, Dylan’s heat-flushed cheeks wedged into one or another black kid’s elbow, book-bag skidding to the gutter, pockets rapidly, easily, frisked for lunch money or a bus pass. On Hoyt Street, on Bergen, on Wyckoff, if he was stupid enough to walk on Wyckoff. On Dean Street, even, one block from home, before the dead eyes of the brownstones. . . Adults, teachers they were as remote as Manhattan was to Brooklyn, blind indifferent towers. (Lethem 84)

And still that does not quite describe what Lethem also calls “a polyrhythm of fear and reassurance, a seduction” (85). In his 2003 essay, “Yoked in Gowanus” (written while he was still drafting The Fortress of Solitude), Lethem explains that yoking was distinct from mugging because mugging was something that happened to adults (103) and yoking was a kind of secret compact that included an element of neighborhood intimacy predicated on the yokee leaving the racial dynamic unspoken. In other words, the liberal value of “assertively ignore[ing] difference” (104), which Dylan’s (and Lethem’s) parents instilled in him, made him feel guilty for thinking this “racial-hazing” as racial at all. (Yet, he later does come to learn that the racial framework he associated with yoking did not mean that young men of color weren’t yoking each other). Dylan suffers a profound cognitive dissonance between the model presented by his parents and the constant acknowledgement of his difference present in his being known as “whiteboy” around the neighborhood. Dylan’s peers of color—much more savvy about white hypocrisy regarding race—sometimes draw him near for yoking by questioning whether his fear is racially-based. This forces him to approach his tormentors or appear as the worst thing he could be: a racist. Such experiences could easily lead to a reactionary response, an internalized racial resentment that let’s itself off the hook because of the belief in the value of not acknowledging race and blaming the Black kids for mentioning it first. As Lethem puts it in the “Yoking” essay, his childhood self was confused by the racialized interactions he was having, asking rhetorically, “Hadn’t we struck a great deal to not mention that kind of thing?” The violation of that received wisdom to never mention race challenged his parents’ “colorblind” values. Such a challenge can be devastating to a young person who never even knew to question its self-evident goodness, let alone consider that racial inequality is an ongoing social problem that their apparent current circumstances may not explicitly reflect. This is something Hazel comes to realize about homeschooling.

As we now know (or should), not mentioning race is not a panacea to racial problems. Newlevant’s mother establishes the choice she made for Hazel as a personal one, about her child’s interests. It can be too easy to not blame a parent for wanting what is best for their child that institutionalized racism is just as easily ignored. No one individual decision makes racism real, but a skein of complex choices nevertheless govern and maintain that racial reality of persistent inequality.

It would be overly simplistic, however, to too directly compare Newlevant’s mother’s experiences and choices with those of a fictional character (however autobiographical Lethem’s novel may be). Firstly, The Fortress of Solitude has a very different setting from Oregon. We’d also have to account for differences in gender in how those encounters played out, were addressed by adults, or were internalized. Nevertheless, it could be valuable to consider the lack of confrontation with that reality (or its source) in both books. As both Joyner and I disappointedly point out, No Ivy League has no point where we see Hazel ask their mother more about her choices or asks her to reconsider her experience of what Lethem calls “the dystopian racial miasma of real experience” (“Yoked” 103). Instead, the realization leads to Hazel questioning their own white privilege, which while admirable, falls short of effectively conveying how an ugly racial reality undergirds her opportunities, and what that might say about broader historical inequalities and marginalization. In Lethem’s book, Dylan never gets to confront his mother, who takes off while he is still quite young. And yet, in the last section of The Fortress of Solitude, we find an adult Dylan still struggling with the racial legacy of where he grew up and the role his presence as a young white kid played in the transformation of his old neighborhood and the dislocation of many of the people who lived there. As a kid, Dylan is a “ghost from the future” (136), a sign that even the blighted neighborhood and substandard housing that poor Black and brown people have been pushed into can be taken from them if white people think they can make a profit from it. Furthermore, Dylan must also come to terms with the second chances he gets despite fucking up—like getting busted selling cocaine in college—while Mingus, his biracial one-time best friend, ends up doing time for similar crimes. Lastly, he has to accept how his fuck ups can have life and death consequences for his peers of color, including a role in the death of his neighborhood nemesis, Robert Woolfolk. Yet, despite all his apparent shortcomings, we know he is trying to figure it out.

Ultimately, The Fortress of Solitude is a work of anti-nostalgia. It presents the veneer of idealized Brooklyn past in order to challenge the narrative of his racial victimization and interrogate that complicated sense of simultaneous belonging and unbelonging. The novel explicitly demonstrates the inability for individuals to make the kind of structural changes to improve life in these communities and the more complex relationships among people within those communities than simply the black and white dichotomy of citizen and criminal. (It explores this in part through a bumbling attempt by Dylan and Mingus to share a superheroic identity). The Fortress of Solitude asks its readers to contemplate the middle spaces (which, by the way, is where this blog gets its name) where no individual significance-defining narrative holds sway, constantly challenging received knowledge about the centrality of our own self in understanding what is happening in the world around us as to reframe it and understand it more deeply. When young Hazel Newlevant is depicted in the library doing their research, they are beginning to dig into a history that profoundly shaped their life but that remained obscured until their experience of harassment and their mother’s admission provided an opportunity to discover the context both those events (and many more) exist within.

Both of these books—regarding white protagonists coming to grips with their parents’ choices and the racial legacies of where they grew up—don’t try to definitively (and thus reductively) make sense of those legacies but remain open to continued interrogation. Where they fail, but perhaps productively so, is in figuring out what the hell to do about it. A careful reading of these texts sheds light upon that very difficulty.

No Ivy League is available from Lion Forge Comics’ Roar Imprint at a variety of booksellers.

Pingback: All We Are Is Dust In The Wind, Dude – This Week’s Links - Avada Classic Shop