I have long had a thing for anthropomorphic robots. Except for my very favorite robot of all-time, R2-D2, as a kid I developed a fondness for cyborgs and androids—the kind of robots that were near-human. They have human intelligence, something of a personality and most importantly a desire to be human. This explains my love of Rom, Space Knight, and why in the 90s, Data was my favorite character from Star Trek: The Next Generation. It explains why in high school I read Isaac Asimov’s novelette The Bicentennial Man like five times (I still have never seen the movie, though). By now, the idea of the robot that wants to be human is a cliché, but even clichés are new to someone at some point and my introduction to that idea was Marvel’s Machine Man.

I have long had a thing for anthropomorphic robots. Except for my very favorite robot of all-time, R2-D2, as a kid I developed a fondness for cyborgs and androids—the kind of robots that were near-human. They have human intelligence, something of a personality and most importantly a desire to be human. This explains my love of Rom, Space Knight, and why in the 90s, Data was my favorite character from Star Trek: The Next Generation. It explains why in high school I read Isaac Asimov’s novelette The Bicentennial Man like five times (I still have never seen the movie, though). By now, the idea of the robot that wants to be human is a cliché, but even clichés are new to someone at some point and my introduction to that idea was Marvel’s Machine Man.

My ideas on the trope have developed quite a bit since those days. Thinking back on it I realized that it was my identification with these human-seeming robots as “the other”—as an outsider that wants nothing more than to find a way to make it “in”—that made them resonate with me. The robots’ desire to belong (even if human life is a bit of a conundrum) echoed my own desire to assimilate into the superior life of middle-class white America as depicted in popular culture. Robots became a way to explore these feelings and identify with a desire without having to have the presence of mind to admit it to myself or anyone else. Looking back I see now that these characters and stories were a way for authors to explore these concepts without the risk of actually addressing the reality of racial politics.

If there is one thing that comics and science fiction don’t do well it’s race. Oh, they often make a noble effort, trying to use aliens and monsters, mutants and merpeople as metaphors for racial and ethnic difference, but more often than not its conclusions and solutions are provincial, over-simplified, or even offensive themselves—never challenging the default assumption of the preferable and superior European-descended white way of life. It is because of this that even when stories do not include black characters and on the surface do not seem to be about race, there is an actual commentary to be pulled from it. The generic “human” these robots want to be is a white human. This sends a message about desirability and possibility of assimilation. These stories make that effort seem noble, even as they provide for robots—which by definition are inhuman and without life—what is socially inaccessible for whole subsets of people who are already human, but often not treated that way.

Asimov’s novelette, The Bicentennial Man (1976) is a perfect example. The robot Andrew, who takes his master’s last name, distinguishes himself through his woodworking and his relationship with “Little Miss,” his master’s daughter who takes the robot’s side in his effort to become human. The robot’s master is depicted as fairly progressive to a point, willing to allow the robot to keep his own bank account for money earned through his woodworking (well, half of it anyway, the master must keep his own spoils), but is resistant when Andrew decides to use this money to buy his own freedom. Even if you haven’t read this story, it is pretty clear that the slavery subtext can hardly be called “sub-” at all. The parallels are many. Andrew’s original robot duties are that of house negro, I mean, butler. And when the topic of his freedom is debated it is done in front of Andrew. As Asimov writes, “For thirty years no one had ever hesitated to talk in front of Andrew, whether or not the matter involved Andrew. He was only a robot,” which should remind any educated person of the social invisibility of blackness in the American South. Furthermore, Little Miss reassures her father that Andrew will remain “loyal,” and that his desire for freedom is not a personal affront to the master. He just wants to be called free, even if in practice his life will not change. “Making him free would be a trick of words only, but it would mean much to him. It would give him everything and cost us nothing.” But it hurt the master that his servant should want to be free. It is better for the master to stew in his feelings than to consider what it means to be even a good and tolerant master, which is ultimately no different than an evil and abusive one.

Asimov’s novelette, The Bicentennial Man (1976) is a perfect example. The robot Andrew, who takes his master’s last name, distinguishes himself through his woodworking and his relationship with “Little Miss,” his master’s daughter who takes the robot’s side in his effort to become human. The robot’s master is depicted as fairly progressive to a point, willing to allow the robot to keep his own bank account for money earned through his woodworking (well, half of it anyway, the master must keep his own spoils), but is resistant when Andrew decides to use this money to buy his own freedom. Even if you haven’t read this story, it is pretty clear that the slavery subtext can hardly be called “sub-” at all. The parallels are many. Andrew’s original robot duties are that of house negro, I mean, butler. And when the topic of his freedom is debated it is done in front of Andrew. As Asimov writes, “For thirty years no one had ever hesitated to talk in front of Andrew, whether or not the matter involved Andrew. He was only a robot,” which should remind any educated person of the social invisibility of blackness in the American South. Furthermore, Little Miss reassures her father that Andrew will remain “loyal,” and that his desire for freedom is not a personal affront to the master. He just wants to be called free, even if in practice his life will not change. “Making him free would be a trick of words only, but it would mean much to him. It would give him everything and cost us nothing.” But it hurt the master that his servant should want to be free. It is better for the master to stew in his feelings than to consider what it means to be even a good and tolerant master, which is ultimately no different than an evil and abusive one.

Andrew is awarded his freedom fairly quickly and easily, all things considered, though he is still the responsibility of his (former) master, but the “trick of words” works. There is no Dred Scott v. Sanford for robots. Andrew is unique, an aberration. All other robots are not only slaves, but they are built purposefully to never develop the abilities and desires manifested in Andrew. As such, as a true metaphor for slavery, The Bicentennial Man fails—for while the institution of American slavery was designed to eliminate the desire and even conception of freedom from black slaves, it could never quite accomplish that across the board. The story, while ostensibly set in the the U.S. of the future, does not makes one reference to the history of American slavery, African Americans or the history of civil rights, eliding an important and ugly historical context. In addition, the story has a sentimental attitude towards servitude. Even when the robot dies (for over the years he has his body parts replaced with parts that work more like humans, and thus by design will eventually fail), all he can think about is his “Little Miss,” like a slave mammy conditioned to love her little white charges more than her own children, and so never leaves the plantation even after 1865.

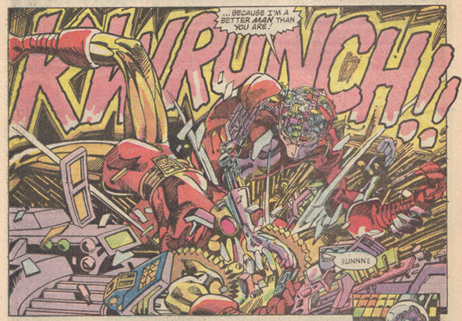

from Machine Man vol 2, #1 – 1984

Machine Man represents a different kind of assimilationist approach.

Machine Man is the creation of “King” Jack Kirby, first appearing the comic series based on 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1977 and then moving on to his own title after that. As my early comic collecting days were before easy access to comic specialty shops, I got my most of comics one of two ways: new comics came from the drug store or newsstand, and older comics came from garage sales and flea markets. It was in the latter way that I got my hands on a lot of issues from that original Machine Man run (comics that I have long ago lost) and fell in love with his quirky attempts at humanity. He even had a day job as an insurance salesman, taking the name Aaron Stack. If anything screams banality of the modern condition, it is insurance salesman. Even in their civilian guises most other superheroes have sexy professions. They are journalists, doctors, newspaper photographers, billionaire playboys or test pilots, but Machine Man was an insurance salesman. I love that.

But what I think I was identifying with back then was his pining for a “regular life,” and to me back then, “a regular life” meant the life I saw depicted in mass media—a life lived predominantly by white people. It is a life implicitly representing “the best life”—a life that reinforces the unspoken white supremacy written into depictions of “the normal.”

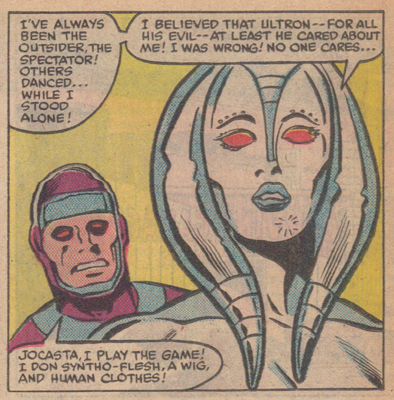

Machine Man’s desires takes on a whole new depth if, instead of a robot, you imagine him being black or Latino. Like Black Goliath, MM’s title didn’t last long (only 19 issues), and thus was later relegated to guest appearances in other books. In a two-part story that appeared in Marvel Two-in-One issues #92 and #93 (in 1982), we see him pining for a blonde blue-eyed co-worker, at least until he meets the female robot Jocasta, and falls in love with her in part because of her own position as outsider and other. In the panel below, Machine Man’s response to Jocasta’s robotic angst is to explain his own way to overcome that feeling is not by trying to live among humans as a robot, but to “pass” by donning “syntho-flesh, a wig and human clothes!” He plays “the game.”

Of course, these two approaches (Machine Man’s assimilation and Jocasta’s resistance) to living among (white) humans are measured against Ultron, the evil robot who wants to destroy all life and replace it with a machine world free of individual autonomy. Like a caricature of a Marxist Black militant, Ultron’s violent solution to the position of robots is predicated on a explicit robot supremacy that obfuscates the more implicit ways that human (white) supremacy pervades society. The good robots must fight the bad robots in order to prove themselves worthy of joining humanity. Sound familiar?

However, Jocasta’s position is still too radical and she has to pay for her outsider position with her life. She can’t assimilate (though she was designed with a curvacious sexualized woman’s body), so she must die. Machine Man is left without a potential partner. However, he would not have to deal with her absence and his assimilating troubles for much longer, because when we next see him he is being reassembled in the distant future of 2020 in a eponymous limited series that came out in 1984.

The world of 2020 is one that developed after the “Robot Riots” of 1999. A poor man’s cyberpunk wasteland where one of Machine Man’s former foes runs a corporation with a cheaply made robot monopoly in a society done under by addictive virtual reality video games. It seems like in this world most people are passive consuming “vidiots,” while those who challenge the the capital-driven welfare economy are outlaws and “Midnight Wreckers” who salvage robot parts in a black market economy that doesn’t seem any more ethical than the corporation they fight against.

[Of course, this makes the limited series sound a lot more interesting than it really is. It is kind of poorly plotted and the conclusion lacks any kind of satisfaction (or even sense), but I think those problems arise from the fact that there were only four issues in which to develop this setting, since the setting is the most interesting part. That said, more happens in one issue of this series than happens in entire multi-issue event series like the terrible Age of Ultron going on right now.]

Jocasta chooses to stay with her evil mistress rather than go with a free Machine Man. (Machine Man vol. 2 #4)

Ultimately, Marvel decided that this was an alternate future, which makes sense especially since we are now closer to 2020 than we are to 1984, but there is something to else be noted about this series that would also make it a world apart from the real one. There are no black or brown people in it! The dark future is white complected and provided with a robotic slave labor force, of which Machine Man and Jocasta, like Andrew Martin in Asimov’s story, are aberrations. In the conclusion, Jocasta (who has also been rebuilt to serve Machine Man’s foe Sunset Bain) chooses to remain with her villainous mistress in a move that is inadequately explained and makes no sense, but that MM claims to understand. It seems that she has given up her desire to be free in the guise of “freely choosing” to serve.

In 1999 (the real 1999) Marvel tried another Machine Man series, called X-51, The Machine Man, but it only lasted nine issues. I can’t comment on it as I’ve never read it, but from what I understand they drastically changed his look and powers, and the changes led to how he’d be portrayed in the comedic comic series NEXTwave by Warren Ellis. In that series Aaron Stack embraces his robot nature, but is also made to avow his hatred of “fleshy ones” and reprograms himself to love beer and feel its effects. He is a drunk lecherous angry robot. This is the version of Machine Man that seems to be most popular and well-known among comics fans these days, and it’s a shame because he was made into a joke. I have no issue with his being made to develop an attitude that leads to his rejecting his assimilationist project or even there being humor added to his character (he was always quick with the snappy patter), but in terms of the subtext I am exploring here the jokiness strikes me as another example of the plight of “the other” only being good for comic relief. It does not help that later still, Machine Man gets his hands on a Monica Rambeau LMD (life-model decoy), essentially a robot black woman, that he keeps as a kind of sex slave that he made sure was programmed to cry. This kind of twisted “humor” mocks Rambeau’s achievements as a black superheroine and transforms MM into something closer to what Ultron was in terms of his creation of and relationship with Jocasta as depicted in those old Marvel Two-in-One issues. I can’t help but wonder if Marvel would ever dare doing such a thing to a white woman character, but then again, they had Ms. Marvel raped by Marcus while she was his prisoner in another dimension, impregnating her with himself so she might give birth to him when she returned to Earth, and then had her go off with him to be his bride.

Machine Man and his Monica Rambeau slave robot (from Ms. Marvel #26, 2008)

I haven’t lost my soft spot for those robotic characters, even if I am a lot more critical of how they are portrayed and recognize the social and historical context such outsider characters exist in and my own relationship to that experience. I am still experiencing/practicing a form of disidentification, but I am more conscious of it. Disidentification, for those who don’t know is a term from queer theory coined by José Esteban Muñoz:

Disidentification is about recycling and rethinking encoded meaning. The process of disidentification scrambles and reconstructs the encoded message of a cultural text in a fashion that both exposes the encoded message’s universalizing and exclusionary machinations and recircuits its workings to account for, include, and empower minority identities and identifications. Thus, disidentification is a step further than cracking open the code of the majority; it proceeds to use this code as raw material for representing a disempowered politics or positionality that has been rendered unthinkable by the dominant culture.

The sympathy I now feel for characters like Machine Man does not only emerge from the difficulty or impossibility of belonging, but also for developing that desire to belong to begin with, rather than being able to exist in their difference and even use their outside position to critique that which is considered normal, default, unquestioningly desirable. “I AM A MAN!” cried signs in the era of the American Civil Rights movement carried by black men who wanted their humanity recognized, and Machine Man inadvertently depicts the compromises expected of the other if he is to be allowed to claim that manhood. Aaron Stack or Andrew Martin or Data or even Warlock from the New Mutants, can be “a man,” because there is no such thing except in being it. They don’t have to change to become human, rather we have to admit that what is “human” is always changing—defined not by what it is, but rather what a dominant group wants to make sure it is not.

Wow. While the connection between robots, civil rights, and slavery is hard to ignore (if I remember correctly, Robot is Czech for slave), the detail to which you brought this is staggering.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on casandersdotnet and commented:

Another great article from Mr. Oyola about Comics, Slavery, and Racial Assimilation

LikeLike

My biggest memory of Machine Man is from Marvel Zombies 3. I just looked it up and he says he has “modeled myself after the fleshies now. I look out for Number One, just like them.”

LikeLike

That is on my list of things to pick up.

LikeLike

Pingback: On Collecting Comics & Critical Nostalgia | The Middle Spaces

you wrote: [ In that series Aaron Stack embraces his robot nature, but is also made to avow his hatred of “fleshy ones” and reprograms himself to love beer and feel its effects. … and it’s a shame because he was made into a joke. … but in terms of the subtext I am exploring here the jokiness strikes me as another example of the plight of “the other” only being good for comic relief.]

I disagree, I think that the current portrayal of Aaron Stack appeals to his fanbase because they sympathize with the subject-position of the politically-dejected intoxicated bohemian dropout. it’s not necessarily a position to aspire towards, but it is a mental-space that plenty of people find themselves (whatever their racial, sexual, socioeconomic status) in these more-overtly fascist times. It is a space of resistance – albeit, an ineffectual passive-aggressive space.

Your blog is great!

LikeLike

Thanks for commenting and I’m glad you are finding the blog a fun and hopefully thoughtful read!

As for this specific comment, I think there is room for both of us to be right. I think your analysis of the character resonates, but you can’t deny that he is meant to be funny. There is a bit of cognitive dissonance in how he simultaneously is a subject for identification and ridicule because of his alienation and his inebriated reaction to it.

Of course, I wrote this piece from the perspective of my personal identification with robot and cyborg characters – so that influenced my interpretation of the current Machine Man, who I find so disappointing.

LikeLike

This is great stuff.

Out of curiosity, have you read Kirby’s original Machine Man introductory story in 2001: A Space Odyssey issues #8-10? It emphasizes the despair and existential angst of the character in a way that was almost entirely erased when Kirby translated him into a monthly series to replace the cancelled 2001. (For hardcore Kirby fans, it has much in common with his use of cloning in Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen a few years earlier.)

That 2008 scene from Ms. Marvel is just…ugh. Ugly and wrong.

LikeLike

You know, I had a chance to pick up those 2001 issues for very cheap not too long ago and I skipped on them and now I regret it.

I thought the change in personality happened when Kirby left the series and they stuck him in the Insurance company (which, btw, was overrun with Dire Wraiths if you read Rom, w/o them ever meeting) – which is awesome b/c I like to think of a robot learning to be a human from being among e il space aliens. :)

Yeah, I can’t get over those plot line either.

LikeLike

Pingback: “I Know It When I See It”- Race, Relatability, and Reading Practice | The Middle Spaces