N.B: In undertaking this project, I soon came to realize how complex and far-ranging it really is, and for every aspect I got to explore, it seemed that there were about five others I didn’t have time/room to excavate to the degree I would have liked. In reality, this would be a book length project, so I am sure readers will have plenty to point out that could be developed further, or that I did not get to address, and I look forward to hopefully discussing some of that in the comments.

Storm of the X-Men is arguably the most prominent and visible black female superhero of any medium—whether it be comics, TV, or movies. Despite this, there hasn’t been much written about her on her own, and this post (first in a three-part series) is meant to address that a bit by closely exploring three comic book issues that focus on Storm and the construction of her identity as a superheroic black African mutant woman. I was inspired to examine these particular issues by Jay Edidin and Miles Stokes of the Jay & Miles X-Plain the X-Men podcast, who not only took the time to have an entire episode about one of these issues, but made the suggestion in that episode that the issue and the character had rich possibilities for a postcolonial reading. As writers like Junot Diaz and scholars like John Rieder have suggested, the colonial imagination has laid a foundational trajectory for the shape and direction of popular culture. As such, having read my fair share of postcolonial thinkers like Edward Said, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Homi K. Bahba, among others, I have returned to Uncanny X-Men #186 (1984) and #198 (1985), and Storm volume 3, #3 (2014) to read them through that lens.

Storm of the X-Men is arguably the most prominent and visible black female superhero of any medium—whether it be comics, TV, or movies. Despite this, there hasn’t been much written about her on her own, and this post (first in a three-part series) is meant to address that a bit by closely exploring three comic book issues that focus on Storm and the construction of her identity as a superheroic black African mutant woman. I was inspired to examine these particular issues by Jay Edidin and Miles Stokes of the Jay & Miles X-Plain the X-Men podcast, who not only took the time to have an entire episode about one of these issues, but made the suggestion in that episode that the issue and the character had rich possibilities for a postcolonial reading. As writers like Junot Diaz and scholars like John Rieder have suggested, the colonial imagination has laid a foundational trajectory for the shape and direction of popular culture. As such, having read my fair share of postcolonial thinkers like Edward Said, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Homi K. Bahba, among others, I have returned to Uncanny X-Men #186 (1984) and #198 (1985), and Storm volume 3, #3 (2014) to read them through that lens.

Colonialism and the “Textual Attitude”

In order to begin, I want to establish my theory that continuity is especially strident against characters of color. Readers accept the problematic racial attitudes and assumptions embedded in American superhero comics as a form of canonical truth that if addressed at all, must be dealt with in a way that cannot change the fundamental white supremacist status quo, or even admit that it is present. Inquiries into entrenched institutional racism within the world represented by these comic stories (one that is meant to reflect our own to a significant degree) must fit the demands of a continuity with a checkered history in regards to representations of blackness. Racism, in order to fit the atomized notion of justice purported by superhero comics, must be something performed by ignorant and/or evil individuals, and any ongoing racial injustice needs to be the work of a conspiratorial cabal run by the Red Skull or Baron Zemo. It’s for this reason that back in the early 70s writer Don McGregor had the Black Panther fight the Ku Klux Klan and not a police department or the board of education. The nostalgia of the comic-continuity pedant insures the recapitulation of racial ideas about characters of color making it very difficult for writers to change that status quo because any effort is subsumed by the ongoing problematic narratives of race in the genre.

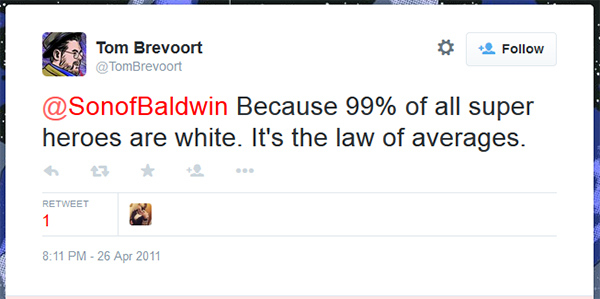

In “Crisis” from 1978’s Orientalism, Edward Said warns us about orientalism’s “textual attitude.” He writes, “It seems a common human failing to prefer the schematic authority of a text to the disorientations of direct encounters with the human.” He goes further, suggesting that “the experience of readers in reality are determined by what they have read,” and of course we “read” not just written texts, but all forms of representation. The authority of the text (in this specific case, the text being Marvel superhero stories serialized over scores and scores of titles since at least 1961) makes the reader look for what appears authentic to that universe, and failing that ways of reading that never fail to reinforce the veracity of the text. “This is how it’s always been” is a frequent justification for maintaining problematic characterizations and skewed demographics, as a way of forestalling alternate possibilities. It’s Marvel editor Tom Brevoort’s old “99% of all superheroes are white” canard. Thus, introducing new POC characters or re-imaging existing characters as people of color becomes “diversity for diversity’s sake,” because the “unerring” text already shows us the “proper” racial and ethnic breakdown of a superhero community. The mindset of the pedantic reader is not all that far from that which undergirds orientalist thinking. Orientalism assumes an unchanging orient—an attitude that assigns an essential character to an arbitrarily defined geographical place that does not change with historical circumstances. We see the world not only in relation to what we “read,” but what we read can frame a complex reality in terms of categories of knowledge that favor Eurocentric and white supremacist ideas, even when a particular story is supposed to be a “positive” representation. At their worst these three stories featuring Storm are recapitulations of that power/knowledge framework. At their worst these stories are a manifestation of a recursive ahistoricity that narrates away the disjunctions between an inaccessible immediacy of a place and the texts that seek to (for better or worse) represent those places and their people. And yet, these issues of Uncanny X-Men and Storm’s recent solo book seem to simultaneously try to explore and make use of those disjunctions, even as they reinforce a stereotypical African narrative of poverty and mysticism.

Marvel editor Tom Brevoort’s now notorious tweet is the perfect example of how a reading of comic canon is confused with a reality to be emulated, all in justifying unequal representation.

The violent condescension that underwrites the colonial project in Africa finds its justification in the results of its own legacy. In other words, whether it is bringing “enlightenment” to superstitious African “savages” that worship non-Judeo-Christian gods, advancing their “backwards” technological capabilities in order to better exploit the continent’s resources, or “stabilizing” political entities frequently established by outsiders redrawing maps to their economic benefit, there is always “a reason” for European intervention (or not intervening in the case of things like South African apartheid) in Africa. Storm provides a site for thinking through the way these orientalist traditions that Said warns us of inform the American superhero tradition, but also illuminates possibilities for reading against the grain to find spaces in the disjunctures these narratives are supposed to paper over to wedge open the “schematic authority” of both historical and comic book continuity and imagine stories for subaltern identities that are obscured through their imbrication with the dominant colonial mindset.

Black Panther & Afro-Futurism

I should probably stop a minute to address the Black Panther and his home nation of Wakanda. Certainly, he is the most prominent black superhero, being the first and the Platonic ideal of the independent, strong-willed leader of his people. However, despite the recent intertwining of Storm and Black Panther through their marriage (and subsequent divorce), he is not the subject of this exploration for a few reasons. The most obvious is that he does not appear in the issues I will be examining—his relationship to Storm was something retconned into a back-up story in Marvel Team-Up #100 (1980), but I do not recall any interactions between these two characters in the time period of my reading X-Men comics. More importantly, Black Panther’s connection to the technologically advanced fictional nation of Wakanda, which has been able to resist colonial forces for hundreds of years, puts him into an Afro-futurist tradition that while in part is a reaction to colonialism, is a distinct kind of representation that is in many ways very distant from Storm’s emergence from a real named country (Kenya) and her participation in an on-going title that ostensibly serves as a metaphor for the struggle of racial, gendered and sexual identity politics. The X-Men occupy cultural hybrid zones. This is clearly by design. The international make up of 1974’s All-New All-Different X-Men in Giant Size X-Men #1 (wherein Storm made her first appearance) is purposefully putting representatives of different nations and cultures together to occupy a marginalized place within the Marvel on-going superhero narrative where their difference is put to use in feeding and revitalizing that narrative. Black Panther’s representation has had its problems (and one day I will get around to writing about Don McGregor’s lauded but problematic run on Jungle Action), but his cultural hybridity only exists on the meta-narrative level (a comic about Africa written and drawn by white American men), while Storm’s is a part of her ongoing story and sense of self (later, it’d be revealed that Ororo is African-American, but was orphaned in Africa, leading to her childhood as a thief and her teen years as a weather goddess).

I should probably stop a minute to address the Black Panther and his home nation of Wakanda. Certainly, he is the most prominent black superhero, being the first and the Platonic ideal of the independent, strong-willed leader of his people. However, despite the recent intertwining of Storm and Black Panther through their marriage (and subsequent divorce), he is not the subject of this exploration for a few reasons. The most obvious is that he does not appear in the issues I will be examining—his relationship to Storm was something retconned into a back-up story in Marvel Team-Up #100 (1980), but I do not recall any interactions between these two characters in the time period of my reading X-Men comics. More importantly, Black Panther’s connection to the technologically advanced fictional nation of Wakanda, which has been able to resist colonial forces for hundreds of years, puts him into an Afro-futurist tradition that while in part is a reaction to colonialism, is a distinct kind of representation that is in many ways very distant from Storm’s emergence from a real named country (Kenya) and her participation in an on-going title that ostensibly serves as a metaphor for the struggle of racial, gendered and sexual identity politics. The X-Men occupy cultural hybrid zones. This is clearly by design. The international make up of 1974’s All-New All-Different X-Men in Giant Size X-Men #1 (wherein Storm made her first appearance) is purposefully putting representatives of different nations and cultures together to occupy a marginalized place within the Marvel on-going superhero narrative where their difference is put to use in feeding and revitalizing that narrative. Black Panther’s representation has had its problems (and one day I will get around to writing about Don McGregor’s lauded but problematic run on Jungle Action), but his cultural hybridity only exists on the meta-narrative level (a comic about Africa written and drawn by white American men), while Storm’s is a part of her ongoing story and sense of self (later, it’d be revealed that Ororo is African-American, but was orphaned in Africa, leading to her childhood as a thief and her teen years as a weather goddess).

It is also worth noting that Storm and Black Panther are our only choices. There may be other African superheroes, but none of them has the same visibility as either Ororo or T’challa. Two characters are meant to stand in for all of “Africa”—at least in the Marvel Universe. There is Batwing over at DC comics, but I know very little about him. It is important to keep this limit in mind as we examine these comic book issues/stories and consider their power to define and reinforce ideas about “Africa” and its diverse peoples.

“Lifedeath”

Uncanny X-Men #186 is a special double-sized issue that came out in 1984 featuring a story entitled “Lifedeath.” Written by Chris Claremont, the issue is penciled by Barry Windsor-Smith with inks by Terry Austin—an artist team in comics that is hard to match. The story follows up with the immediate aftermath of Storm having lost her powers in the previous issue as a result of a government weapon designed by Forge, her current host and care-taker. In issue #185 when Forge shows up to stop government agents from using the technology he designed for them (what did he think would happen?) he ends up rescuing a depowered Storm from drowning in a river and brings her to his technologically advanced home. This is actually rather an odd situation, because as far as I could determine Ororo and Forge had never met before that issue, and yet, as readers we must accept that something’s happened between them since that unconscious rescue. Ororo awakens in Forge’s home at the outset of “Lifedeath,” but appears to know who he is and despite her (or perhaps because of) despondent condition, she appears to trust him well enough and have a warm feeling towards him. She does not question him about who he is, why he was present at the scene when shifty SHIELD agents arrived or why he is helping her. She won’t even know that he is a mutant too until near the end of the issue. Let’s call this acceptance of their familiarity macro-closure, an important reader-provided practice that makes serials cohere. Accepting this unseen development is crucial for this story to make sense given not only the emotional reaction to Forge’s unintended betrayal of Storm that comes later in the story, and its subtitle, “a love story,” provides a frame for understanding the relationship between these two characters. The emotional connection they share is a narrative device to explore the intimacy of identity.

Uncanny X-Men #186 is a special double-sized issue that came out in 1984 featuring a story entitled “Lifedeath.” Written by Chris Claremont, the issue is penciled by Barry Windsor-Smith with inks by Terry Austin—an artist team in comics that is hard to match. The story follows up with the immediate aftermath of Storm having lost her powers in the previous issue as a result of a government weapon designed by Forge, her current host and care-taker. In issue #185 when Forge shows up to stop government agents from using the technology he designed for them (what did he think would happen?) he ends up rescuing a depowered Storm from drowning in a river and brings her to his technologically advanced home. This is actually rather an odd situation, because as far as I could determine Ororo and Forge had never met before that issue, and yet, as readers we must accept that something’s happened between them since that unconscious rescue. Ororo awakens in Forge’s home at the outset of “Lifedeath,” but appears to know who he is and despite her (or perhaps because of) despondent condition, she appears to trust him well enough and have a warm feeling towards him. She does not question him about who he is, why he was present at the scene when shifty SHIELD agents arrived or why he is helping her. She won’t even know that he is a mutant too until near the end of the issue. Let’s call this acceptance of their familiarity macro-closure, an important reader-provided practice that makes serials cohere. Accepting this unseen development is crucial for this story to make sense given not only the emotional reaction to Forge’s unintended betrayal of Storm that comes later in the story, and its subtitle, “a love story,” provides a frame for understanding the relationship between these two characters. The emotional connection they share is a narrative device to explore the intimacy of identity.

Understanding the relationship between Ororo’s powers and her identity requires going back to her first appearance in Giant Size X-Men #1. In that issue, Professor Charles Xavier seeks out Ororo in Kenya, where she is playing weather goddess to a tribe of African people. Xavier offers her a “real” world as opposed to the “fantasy” she’s been living in her role as storm goddess. In the vein of comics of the time, in order to move the main plot along, Ororo agrees to the professor’s offer, taking on her “mutant responsibilities” in America, without writer Len Wein having her spend a moment to consider her responsibility to her people in Kenya, or to other mutants of her race. Furthermore, Storm’s depiction implies a primal connection to the elements and to an apparently “primitive” tribe that offers her animal sacrifices for her help with a drought. This brief scene establishes a mythical Africa as the foundation for Storm’s identity, combining her powers with her racial and geographic origins. In other words, there is a sense of primitive African mysticism overlaid on her mutant origins. Her powers continue to be written with an “Earth Mother” vibe—a deep connection to the earth and its environments, that these days is written to be near-god-like with her ability to effect the weather.

Understanding the relationship between Ororo’s powers and her identity requires going back to her first appearance in Giant Size X-Men #1. In that issue, Professor Charles Xavier seeks out Ororo in Kenya, where she is playing weather goddess to a tribe of African people. Xavier offers her a “real” world as opposed to the “fantasy” she’s been living in her role as storm goddess. In the vein of comics of the time, in order to move the main plot along, Ororo agrees to the professor’s offer, taking on her “mutant responsibilities” in America, without writer Len Wein having her spend a moment to consider her responsibility to her people in Kenya, or to other mutants of her race. Furthermore, Storm’s depiction implies a primal connection to the elements and to an apparently “primitive” tribe that offers her animal sacrifices for her help with a drought. This brief scene establishes a mythical Africa as the foundation for Storm’s identity, combining her powers with her racial and geographic origins. In other words, there is a sense of primitive African mysticism overlaid on her mutant origins. Her powers continue to be written with an “Earth Mother” vibe—a deep connection to the earth and its environments, that these days is written to be near-god-like with her ability to effect the weather.

Storm’s first interaction with Professor X in Giant Size X-Men #1 (1974). Click on image to a larger version.

I should also note that not too soon before the events of Uncanny X-Men #186, Storm went through a visual transformation, cutting her hair into a mohawk and donning leather pants and vest—a No Future kind of look that emerged from her association with the Morlocks (sewer-dwelling outcast mutants that cannot or do not want to “pass” in human society). This change from goddess-garb to punk rock duds represented a severe change in reader understanding of Storm’s relation to the world. Here she is, a black African woman navigating American culture as a way to express something about herself that wants to break free of the pedestal that godhood puts her on. Yet, her powers, and through them her role in X-Men, help maintain the continuity of her sense of self. When Ororo loses her powers the identity narrative that coheres through them collapses. Suddenly, both her connection to her roots (as the reader is to understand them) and what makes her part of the mutant community are in peril, and Claremont and Windsor-Smith take a substantial part of two issues of a comic that is mostly about giant robots, space adventures and soapy teen angst to explore this.

Three-fourths of the issue in which “Lifedeath” appears is dedicated to the ongoing conversation and interactions between Storm and Forge. The remaining 11 pages of the comic are mostly devoted to following Rogue and the SHIELD agents from the previous issue and the introduction of dire wraiths from the ROM comic series. As the antagonists in this (and the next) issue of X-Men the dire wraiths seem pretty superfluous, though as someone who followed both titles at the time I loved it, and I think the wraith scenes are well plotted and full of tension and a sense of real peril. The art and writing is sharp. Yet, the dire wraiths’ project of expansion and assimilation/destruction provides a compelling resonance with the colonial legacy that are part of both Storm and Forge’s backgrounds (he’s Cheyenne Native American), as the dominant American culture faces its own invading force. As much as I love the ROM comic, if you go back and count the number of black characters in that invasion of the body-snatchers type sci-fi horror comic, it is not hard to come to the conclusion that its vision of the America to be defended from the alien infiltration was lily-white. The alien invasion narrative provides a way for Euro-Americans to vent their fear of coming under a colonial power, and as such is both evidence of the awareness of the destructiveness of such power and a means to for it remain at a level of remove from the actual history of colonialism. The latter is necessary or else such stories would serve to justify whatever means the colonized undertakes to fight off and resist the colonizer.

Claremont crafted a complex exploration of identity in these story lines. Storm is only in the position to lose her powers because she is trying to help Rogue, who is having her own identity crisis at that time, unable to always distinguish between her own feelings and memories and those of Carol Danvers whose personality and powers she absorbed back in Avengers Annual #10 (1981). The identity shattering violence that Rogue perpetrated against Carol Danvers at the behest of Mystique may seem like typical comic book superhero shenanigans (though as a teenager, I identified deeply with Rogue’s confusion and anomie), but when that trope is extended to Storm, suddenly the echoes of how colonial oppression is also a kind of identity-shattering violence begin to resonate. Uncanny X-Men #186 opens with Storm in bed at Forge’s house, nearly catatonic and trying to decide if she should even go on living without her powers since they are so fundamental to how she defines herself.

While Storm’s powers and identity are the focus of this story, it is Forge’s own history and role in creating the technology that robbed Storm of her powers that provides context for a postcolonial reading. As a Native American employee of the United States government he is already in a precarious position of working for the institution that robbed his people of their sovereignty, but his time fighting in the Vietnam War and his resulting disfigurement (losing his leg and hand and suffering from a lot of other bodily scars) is a physical manifestation of imperial violence that can shatter the sense of identity. He explains to Storm that like her, he felt like dying after losing his limbs, but that he had to keep on going. “With life, there are always options, possibilities—hope.” It seems that for Forge, however, a prerequisite of that hope is a lack of consideration of the systems that lead to that loss.

While he would in time become a member of the X-Men and other X-related super teams, Forge is something of the villain here (though a sympathetic one). He is responsible for Storm’s loss of her powers and seems to not understand (or willingly ignores) the historical context of his choices aiding in the persecution of a minority group that he is a part of (mutants), while also being part of an actual real world marginalized group that has its own confusing history of resistance, capitulation and even aiding the dominating cultural and national force that worked towards destroying them. Forge is no Muhammed Ali when it comes to feeling solidarity and responsibility with other marginalized groups, that’s for sure. The betrayal Storm feels when she discovers that this man she has just started a romance with (seemingly out of nowhere) is the one who designed the gun that left her powerless and that he has been keeping the truth from her has a double valence, in that the betrayal is also against a sense of shared subaltern identity.

Forge is somehow proud of his heritage while not thinking it has anything to do with who he is. Sounds like lip-service to me.

This is made apparent in a scene where Storm and Forge are sharing champagne and awkwardly flirting. She asks, “Forge, you are an Indian?” And he replies that while he is “proud of [his] heritage” it “has nothing to do with who I am or the life I lead.” He even uses the past tense “was” to describe his Cheyenne identity. For later, when confronting Forge about what he has done (and failed to do) Storm asks, “What else did you sacrifice along with your heritage: honor, decency–humanity?!” She makes a direct connection between his untrustworthiness and his relation to his racial identity. In other words, she calls him a race traitor.

The scene proceeding this reinforces the degree to which Forge is capable of ignoring the historicity of his relationship to colonial power. When Storm tries to escape Forge’s futuristic home, the house’s ability to generate three dimensional images of past experiences accidentally transforms the scene into the very battle in Vietnam where Forge lost his leg, revealing that it was not a Viet Cong bomb that disfigured him, but an American one—“friendly fire” from a B-52 bomber. The manifestation (and details) of his wartime trauma makes Storm’s accusation all the more biting. Forge does not even seem to have the dignity to consider his relationship to the cost of the Pax Americana, even though his arm and leg were literally a part of that cost.

While Forge is trying to use his own example as someone who persevered despite his loss to inspire Storm to go on without her powers and not give in to a suicidal depression, he also provides an example of how such individual success is meaningless without understanding the social context for the obstacles an individual faces as a member of an oppressed minority. Forge’s equivocation to state power and the dominant culture in the face of his own bodily destruction emerges from a colonial condition. In Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon explores the psychological effects of the dehumanization on the colonial subject, and here Forge is literally dehumanized, replaced in part by robot parts made possible by his mutant power to invent things. One of these psychological effects is acquiescence to and internalizing of the master/slave narrative. Fanon goes on to advocate violence as the cathartic requirement of the liberation of the colonized, but while X-Men can evoke the affect of resistance, it cannot actually even obliquely follow through with the possibilities of such resistance without undermining the genre as it is understood by most of its readers. Sure, X-Men comics have the team fight elements of the U.S. government at various times, but they are always depicted as loose cannons working independently of the “basically reasonable” central government.

Seeing the source of Forge’s disability after discovering his involvement with the agents seeking Rogue and that cost Storm her powers, it is easy to see why she accuses him of not caring about anything but himself—and perhaps not even that much. There can be no understanding of a self outside of the contexts he seems to want to deny. Storm calls Forge “a me that might have been,” having realized that her loss of powers does not rob her of her relations to her origins, nor does it relieve her of the responsibilities she has taken on in life. If anything, it is this sense of loss that increasingly defines the shared identity of subaltern people.

What that means now that she does not have powers, however is something she still needs to figure out, so over a year later (who knows exactly how long in comic book time) she makes a pilgrimage back to East Africa to re-connect and find her “self.” This is the story of “Lifedeath II” (which I cover in two weeks in part two).

The Art

Both Chris Claremont and Barry Windsor-Smith are credited under “Story” for “Lifedeath.” I wonder if this simply because the nature of comics means that all artists are contributing to the story by virtue of how they draw what the writer dictates (and this is especially true in the old “Marvel Method”), or if he had input on the content of the comic in a more fundamental way. I ask this because so much of what works in this issue (and its sequel 12 issues later) comes from Windsor-Smith’s art. He draws Storm in a way that makes her more real. She is less a voluptuous superheroine in bathing suit and cape, and a more sinewy, lean, strong-looking one. She is still attractive, but the depictions of her, even in the nude, while beautiful, are never overtly sexualized. She is not infantilized either, despite her vulnerable state. Instead, she contains an impressive maturity and authority, even when she is unsure of how to go on. Windsor-Smith’s art provides a necessary intimacy to make Storm evince a palpable complexity and depth.

Forge seems to want to establish his bond with Storm through their elite positions despite being members of a racial minority in America. He has a complex attitude towards his position, but it seems to veer towards self-hatred.

This is not to say that Windsor-Smith’s representations are perfect—though in the case I about to bring up, it may be more accurate to lay this at the feet of the colorists, Glynis Wein and Christie Scheele—because Forge’s skin tone looks weird to me. It is as if they struggled to represent him as a “red Indian” without resorting to a feathered headband. Some panels are worse than others. It is not as bad as it could be I guess, but it is a bit glaring in a comic that is otherwise visually detailed and amazing, and that I would hold up with any of the classic stories of the 1980s that worked to shift our understanding of superhero comics.

Cruel Seriality

The problem is that “Lifedeath” and its sequel gets kind of lost in the X-Men comics’ convolution, but the more time I spend with this story the more I really like it and am impressed by how it is woven into the Claremontian farrago of 1980s X-Men. That being said, by the very next issue (#187) anything interesting being done with the representation of these two characters is quickly undone, swallowed back into the continuity urtext that requires a character like Forge to have a “spirit-sight” and a “soul-link” with his feathered-headband wearing mentor Naze, and for the contemplative mood of “Lifedeath” to crumble so that the X-Men narrative can get back on track with its involvement with the licensed comic based on a defunct toy line. The “textual attitude” of writers, editors and readers insures that whatever momentary space is created to explore the trajectory of colonial thought in comics is swallowed back up into the narrative that has very limited understandings of the colonized subject because each example becomes part of a schema whose meanings come pre-determined by dominant Eurocentric ideology.

Still, I still think we need to highlight strong stories with strong possibilities when we find them.

In part two of “Imperfect Storm: Exploring Lifedeath II,” I will look closely at Uncanny X-Men #198, which follows Storm in her sojourn back to East Africa in search of something that helps her understand her self and her role in the world more clearly.

Excellent piece! Can’t wait to read part 2!

LikeLike

Yes, excellent piece.

Have you read Barry Windsor-Smith’s Adastra in Africa, Osvaldo? Apologies if I’m telling you something you already know, but he reworked pages originally done for a third Lifedeath in the late 80s by changing Storm into one of his own creator owned characters (which suggests his input into the writing side of things was more than just “Marvel method”) Theres a short excerpt at

http://www.barrywindsor-smith.com/studio/adastranews.html

Seems like it might be relevant….

Can’t really comment on Lifedeath itself as I haven’t read the first two for ages (never read the more recent one) but I’ll catch up soon as I can, because Storm is an interesting (but often poorly used) character. Definitely worth writing about.

On a more general point, about the way racism is personified in evil individuals – I don’t disagree with what you say about continuity and nostalgia, but theres also the limitations of the genre. The Black Panther also fights the Ku Klux Klan because superheroes are a personification too, and…. well, its guys in masks hitting each other. Fighting the board of education is something different isn’t it? I mean, social change is achieved by social groups rather than single individuals.

LikeLike

I had heard of Adastra but never saw any of it until now. Looks beautiful. Sometimes I wonder if BWS’s works is just better sans color. Thanks for the link.

As for the limitations of the genre. . . well, sure there are limits, but it can also explore those limits. I actually think a Black Lightning series where he “fights” the board of education would be awesome. I’d like to see people use their powers for something other than punching, like for civil disobedience.

LikeLike

Pingback: Imperfect Storm (Part Two): Exploring “Lifedeath II” | The Middle Spaces

Really enjoyed reading your critical essay. I too have a deep fondness for these issues. Back then I remember being thrilled by this quiet introspective story that probed racial identities. I love the superhero genre too and any time something like this occurred, it was cause for celebration. A sign that the medium was maturing, reflecting the other populations buying and reading these products. And you’re right, we should note “strong stories with strong possibilities” when found. Claremont was breaking ground back then and even young naive readers like I was back in the day felt it and were aware of it. Back then, it felt like I was always watching the white kids play with their neat toys and such stories were “gifts”; they opened a fissure in that immense wall. I think such “daybreaks” as these stories have lead (perhaps too slowly) to new realities.

So definitely, today, we can and should and need to push for better stories where, as you envisioned, superheroes not only fly into the stratosphere to fight the Monster of the Week, but also stop by the local primary school to solve non-violently an issue of discrimination, prejudice, etc. The reader is more sophisticated (probably always was more sophisticated) and the reading population is more diverse. Rather than being “swallowed back into the continuity urtext” such stories/perspectives/attitudes should become the norm.

I never got the chance to read Postcolonialism other than to identify it as a critical theory, so I really enjoy seeing the practical implementation of it in your essays. Look forward to Part Two!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey! Thanks for commenting and I’m glad you found this post informative and thought-provoking. I only just scratch the surface with postcolonial theory here (and in the next two parts), but I couldn’t recommend reading Edward Said’s work (at least “Crisis”) enough,

LikeLike

Pingback: Imperfect Storm (Part Three): “Return of the Goddess” | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Additions, Corrections, Retractions | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Marvel Five-in-One: Prominent, Notorious and Invisible Black Lives of the Marvel Universe | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Girl, You’ll Be an Invisible Woman Soon: Defining Serial Characters | The Middle Spaces

I have been reading your blogs for the last couple of weeks with enjoyment. This was an interesting first part I will look forward to read the other parts as well. I have recently brought but not yet read Don McGregor’s Panther Rage. It seems like you haven’t made any blogs about it. I made a search for Don McGregor and this was the only hit I got. I have heard good thinks from the run including Dwayne McDuffie so my hopes I quite high. I think is was kind of interesting it should be problematic and would would love your to know your reasons. Sidenote I’m currently reading Deathlok by Dwayne McDuffie an interesting read especially after having read your blog about cyborgs and how it relates to being a black person. I’m only four issues in and the theme is already very present there.

Moving on to address this topic more directly or at least it is related to the X-Men and them as a representation of minority/stigmatised groups in society. A problem I have with mutants as metaphor for minority groups and why I find it problematic is the fear of mutants is a real threat and legitimate fear. Fear of people controlling weather, shooting laser beams out of their eyes or controlling peoples mind would be something a society would have to deal with (just like a society would be expected to deal with gun violence). Their powers could (and in the Marvel universe they have) cause major havoc and destabilisation of a society. Hence it is their powers which can actively do something which is feared. Fear of a skin color, sexual orientation, gender or gender identity is illegitimate fears since those characteristic can’t actively do anything to threat the wellbeing of a society more than anybody else. I don’t neglect how it has been used and it can work (one of my favourite X-Men stories is God Loves, Man Kills). I just don’t think it is a analogy with its own problems.

LikeLike

Tobias! Thanks for commenting.

I hope to write about Don McGregor’s Black Panther one of these days, but probably not until way after the movie comes out (I don’t want to come off as raining on the parade of joy people seem to be having in anticipation of the film). My biggest issue with it is the disconnect in how it portrays the common people of Wakanda as backwards and superstitious jungle people, in comparison to what I imagine Wakanda should be like and even how Kirby portrayed it in Fantastic Four. I think I need to read more of Kirby’s own 70s run before I write more about Black Panther, period (but I did write about the first collected trade of Coates’s run for the Los Angeles Review of Books)

As for the mutant metaphor problem, you are not the only one to have brought up this issue. That being said, I think there are two issues to consider about this perspective. 1) Non-mutant superheroes are just as dangerous as mutants, so narrowly identifying one identity as particularly “dangerous” is wrong, 2) Singling out an identity group because of the potential dangerous actions of a subset of them is still not okay. It is that reasoning (for both earnest and cynical reason) that has justified the horrendous treatment of lots of people historically.

All that being said, I still think instead of the mutancy metaphor standing in for other kinds of difference, it is much better if used in ways that intersect with existing forms of difference like race, gender, ability and sexuality.

I hope you keep reading, Tobias, and will comment again.

Oh, and P.S. I didn’t write the Cyborg post, that was guest post by Robert Jones, Jr.

LikeLike

Hey Osvaldo! Thanks for replying

I know it isn’t a revolutionary or new standpoint however it isn’t one I see discuss or address very often. Maybe I have just not be at the right places on the internet. As to the first point clearly anybody with supernatural powers is a potential threat whatever that person is a mutant, mutate, alien, god, demigod or something else. The threat is the same no matter who it is. However there is a difference between mutants and all the other groups of superheroes. An important factor is mutants power is often discovered if not in public places then with an audience. I do ascribe this more to have been done to add some drama to the story. It then overtime just became a part of the mythos. Maybe I’m wrong here. Anyway getting the mutant powers is often embarrassing just like puberty is for many teenagers. Most superheroes have their powers concealed and have a secret identity. A mutant is in many cases outed from the start. Mutants would because of this be easier to discover not to mention making test for the X-Gene in it self would be easy. It would also be easier to make a vaccine/cure against the X-Gene. It would be harder to treat gods, aliens or mutates unless the radiation worked in the same manner in all cases. If a society can partly control a problem or threat be regulation it would be expected to act on it. A solution to the threats from mutants would not eliminated the “threat” from Spider-man and others like him. However it at least it would fix or reduced one aspect of the problem. As for the second point I would ask what horrendous treatment treatment of mutants would be. Would requiring taking a vaccine/cure be wrong? Would a registration be wrong? As I like to say all people have human rights however we don’t have mutants rights

P.S. A sincere apology to you Robert Jones, Jr. it was not meant to discredited him in any way or form. I remembered it as being Osvaldo being the author. Should have check it, I didn’t. My mistake.

P.P.S As I said I have yet to read it however this first page from issue 53 for me seems to dwell in stereotypical portrayal of Africa. http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-v-2dcuuCqHI/UQzIIfbw8VI/AAAAAAAAFLY/RosVRTxY6zQ/s1600/09%2BFantastic%2BFour%2B53%2B%28julio%2Bde%2B1966%29.jpg

LikeLike

I think your observations about the discovery of mutant powers are on point, in that if the mutant metaphor makes sense, it makes most sense as a metaphor for adolescence, not necessarily race or sexuality. Or maybe it is the flexbility of the metaphor that makes it both useful and limited.

As for Kirby’s Wakanda, it certainly is not free of stereotype, and I think that panel is troubling, but in terms of his vision of Wakanda itself, and its blending of advanced technology and natural environments – and a sense of the people itself being educated and capable, no matter what they dress like or what their customs are, is better than what has been represented in other BP books, like MacGregor’s.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Like a Phoenix: On Selective Completion & Re-Collecting X-Men | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Epic Disasters: Revisiting Marvel & DC’s 1980s Famine Relief Comics | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: “Say It Loud!” Tyroc and the Trajectory of the Black Superhero (part 2) | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Year-End Meta 2022: “Escaping Total Nullification” | The Middle Spaces