Editor’s Note: Today’s post is our second guest post on the New Teen Titans (or one of them anyway). If you are interested in writing something for us, click the “Submit” button on top and contact us.

DC Comics’ Cyborg is my least favorite black character currently being published in comic books. He illustrates how the black body functions in a white supremacist framework and embodies so many different offensive stereotypes of black people that it is necessary to enumerate these characteristics as some of them may be missed by the casual reader, while others work as complicated dichotomies, masking the problematics beneath superficial attempts at “post-racial” inclusivity.

For the uninitiated, Cyborg (aka Victor Stone) was created by Marv Wolfman and George Pérez for their wildly successful 1980s revival The New Teen Titans. Back then, Cyborg was the black hero in a comic that mistook tokenism for diversity. He spent a great deal of time mourning his plight as an accident turned him from a star athlete into a human/machine hybrid. Even though this accident gave Cyborg powers beyond those of mere mortals, he considered himself a freak. All he wanted was to be a “regular” human being. The rest of his time was mostly spent secretly longing for a white woman, Sarah Simms, who teaches him how to love himself. During his emotional love affair with Simms, Stone was in a relationship with another woman, a black scientist by the name of Dr. Sarah Charles.

Batman and Catwoman delivering the ragged torso of Victor Stone to his father (from Forever Evil #2 – Dec 2013).

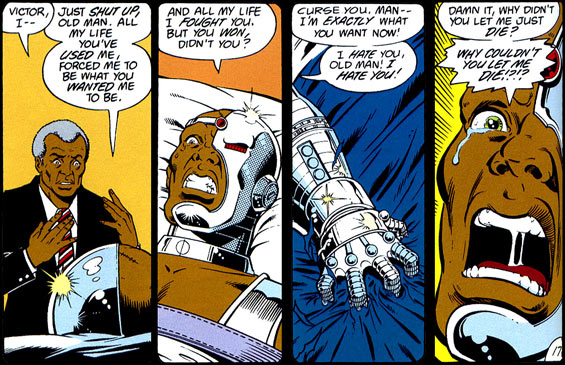

Victor Stone whined and complained and was possessed of a great deal of self-pity, which seemed to be some sort of subtextual commentary on how white people feel about black people’s complaints regarding structural and social anti-black racism and white supremacy. Through Cyborg, the white gaze was able to position black people and our grievances against our circumstances as not only invalid and pitiful, but also as self-inflicted (Victor’s mother and father, Drs. Silas and Elinore Stone, experimented on their son and Silas was essentially responsible for the accident that required his son’s transformation). It was always, to me, even reading these books as a teenager, a deeply problematic view of the plight of black people (it was white people, after all, who experimented on black people in this country). But this view of black people as the source of our own suffering was to be expected; these were the Reagan years after all. But, for the most part, Cyborg was all black kids had. So we ate the scraps we were given.

In the “New 52” retconning of the DC Universe, Cyborg is a founding member of the Justice League, the token minority replacing the former (imaginary) token minority, J’Onn J’Onzz, the Martian Manhunter, and sitting right alongside the token woman, Wonder Woman. This is no accident. For many white people, diversity and tokenism mean precisely the same thing, but beyond that, they are also looking for a particular brand of marginalized person to include; someone who will not disturb the existing state of affairs, who will operate, essentially, as a white, heterosexual, gender-conforming, middle-class man, but in slightly different drag. In his previous incarnation, it was unclear whether Cyborg was a fully functional, sexual being. In the New 52, it’s clear that Cyborg has no genitals. The accident that turned him into a cyborg has taken every bit of his flesh other than his torso, arms, neck, and head. Thus, it’s safe for him to be around Wonder Woman as he serves no sexual threat and no competition for Superman. (I should note that, at the same time, Wonder Woman loses her personhood to become the prize. Please watch the animated film Justice League: War if you don’t believe me. You’ll see the male members of the team, except Cyborg of course, each attempt to call “dibs” on her—including the pubescent Billy Batson/Shazam.) This, to me, is the comic book version of the historical castrations that white supremacists often enacted against black men, of whose sexuality (which they exaggerated and demonized) they were enormously envious and frightened of. Cities in this country were bombed to oblivion on the word of lying white women falsely accusing black men of rape.

At the same time, conversely, Cyborg serves in the racist mold of “the Buck.” So, of course he’s an athlete; of course he plays football. White supremacy must always find some “productive” use in black bodies, must always be able to capitalize off of our labor. Oftentimes, when white writers are attempting to write black characters, they rely on stereotypes because they can’t imagine black people as actual human beings. These are the creations of people who don’t know any/many black people, but have seen plenty of them at basketball games or on television, or maybe even had a beer with one once, and considers them a “friend.”

Cyborg is also the resident chauffeur, “Boom Tubing” the Justice League wherever they need to go—Hoke Colburn to the Justice League’s Miss Daisy. He is their digitized administrative assistant, interpreting and relaying data at their command, serving, actually, as their very means of communication—as much of a tool for the League as a cell phone or as enslaved black people were to the plantation owners of the American antebellum period. And the stereotypes don’t end there. He’s best friends with a young white boy (who transforms into the adult hero, Shazam), a relationship that is nothing more than an updated version of Jim and Huck from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, encompassing the same racist subtext that places black adults on the same emotional and psychological level as white children.

Could Cyborg be the comic book superhero representation of white supremacy’s effect on the black body? To have a black person transformed from a metaphorical machine to an actual one? Whose fantasy is this? Cyborg has the distinct textual feel of some white person’s answer to the question: What would it be like to bring a lynched black person back to life? The problem is they’ve gotten it entirely wrong and I think that’s on purpose. They’d imagine that person being compliant, thankful, eager to please white people, and not a disruptive and liberating figure of rage? Mary Turner, her husband, and her baby, shaking the rafters of every house in America for nearly 100 years now, tell us a great deal about the aggrieved souls of lynched black folk. Compliant is not in their ghostly vocabulary. These haints mean business.

Sufficiently neutered, Cyborg is DC Comics’ idea of a black character safe enough to be embraced by white people. So he’s leapt out of the comic books and onto television screens. On television, in Teen Titans Go!, Cyborg is the comic relief. To be fair, all of the characters are comic relief, though; it’s a comedy. But there’s a certain racially offensive tenor to Cyborg’s shenanigans. Like when he goes into stereotypical black woman pantomime: “Girl, that girl is bad girl news, girl!” and the like. And, since Billy Batson is unavailable in this version, he’s the best friend of the trickster white boy (who happens to be green) to keep that Huck and Jim vibe going.

Soon, Cyborg will have his own film (starring an actor that is at least three shades lighter than Cyborg’s color in the comic books) and his own comic book, written by a black writer, David Walker, and drawn by one of the best artists in the business, Ivan Reis, who hails from Brazil. That he’s being written by a black person and drawn by a person of color may prove to be meaningless and immaterial, however. People of color, including black people, are just as capable of perpetuating white supremacist ideals as anyone else (see Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas or CNN host Don Lemon). And the writer and artist are also subject to the whims of the corporation that owns Cyborg, a corporation that has proven itself to have neither the foresight nor the insight to produce anything but the most banal and unimaginative of material, catering, mostly, to the lowest common denominator, hoping that economic (and psychological) prosperity might be found there. Therefore, we cannot expect some radical shift in Cyborg’s depiction in Walker and Reis’ hands. He will not suddenly grow a penis. He will not refuse to be the mule for League business. He will likely not have any black friends of his own age to shoot the breeze with. He will likely not be in a healthy and loving relationship with a black woman. He won’t be saving the Aiyana Stanley-Joneses and Tamir Rices of the world from the police. He will likely continue his role as one of the police. And it is in this particular lost opportunity that I am most disappointed.

I’m not sure it’s fair to place such a heavy burden on Walker and Reis, as what they have to work with is 30 years of the problematic representation listed above. Nevertheless, this must be said: The mainstream comic book industry is afraid to tackle the notion of what a truly radicalized black person with superpowers would actually look like and what they do with those powers. They don’t want to discuss what they would tear down and who they would free, because to do so would be to frighten a great deal of the white people they believe to be their primary audience. So instead, we get a few of these token Negroes who are complicit with the status quo, who challenge nothing and who change nothing because, if we’re being honest, that’s just the way most white people fantasize about racial issues. White America wants black people either docile or caged. Or dead. (And I base that educated guess, as James Baldwin once said, on the state of American institutions and the performance of the country itself.) Isn’t that what the research reveals, that right alongside magical and impervious to harm, white people also see us as dangerous and scary? That is to say, White Americans see black people as both superhuman and quasi-human at the same damn time. Full ranges of humanity are reserved only for the people they consider full human beings.

If the Cyborg comic book and film do well, white supremacy will be fine with that since he was designed to be the epitome of black harmlessness and profiting off of blackness is something white supremacy has been doing so well for hundreds of years. If they don’t do well, however, it will be a…black mark on all attempts for a solo black character to have a franchise of their own. You know how it works in the world of white supremacy: If a product featuring a marginalized person does well, it’s a “fluke” (it is not as if the success of the Blade films, for example, led to a string of black superhero action movies); if it does badly, it’s because of their marginalized status. This, then, leaves black consumers once again deciding which is worse: bad representation or no representation at all. I don’t purport to have the answer to that quandary.

I was walking to the train station a few weeks ago and a black dad was having a conversation with his two elementary-school-aged sons. They were talking about Cyborg. The kids had so many questions and their father had so few answers. I wanted to intervene and share everything I knew and everything I thought, but there was no reason in the world for me to break those kids’ hearts. Those kids loved Cyborg. I could tell by the way their eyes lit up when they were talking about him. It reminded me of the first time I encountered Black Vulcan on The Super Friends. His appearances were few and far between, but I relished every one of them and in the schoolyard, all the black kids—boys AND girls (there were no black, female superheroes on television at the time; so the girls, too, had no choice)—fought over who would be Black Vulcan when we played superheroes because he was the closest thing to any of us that any of us had. So I walked on past the father and his children, but I still haven’t stopped thinking about those children. They’re me at their age and so they’re blissful and probably in their own schoolyards fighting over who is going to be Cyborg. They don’t yet have the gift of discernment that would enable them to recognize the not-so-surreptitious messages being sent to them via this particular piece of racist propaganda.

But I recognize it.

And so whenever I encounter Cyborg, I feel the same way I did when Condoleezza Rice went shoe shopping as thousands of black people suffered in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina—and didn’t, at first, understand what the big deal was. I feel how I do when Clarence Thomas co-signs on a ruling that penalizes marginalized people. I feel how I do when Don Lemon and Pharrell Williams talk about “respectability” and “new blackness.” I feel a deep, abiding shame, but more importantly, a rigorous distrust.

Whose heroes are these?

Not mine.

Robert Jones, Jr. is a writer and editor from Brooklyn, N.Y. He is the creator of the social justice media brand, Son of Baldwin. He is currently working on his first novel. Follow him on Twitter @sonofbaldwin.

Pingback: “Jimmy Olsen—SUPER Freak!” – Disability and Superman’s Pal | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: BFAP #73: Titans of Technology – LeMar McLean

Pingback: (Behold?) The Vision’s Penis: The Presence of Absence in Mutant Romance Tales | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: 500th Post: David F. Walker Syllabus – Interminable Rambling

Pingback: Micronauts #5 (May 1979) | garyhollingsbee.com

Marv Wolfman is Jewish, not white, and in that context this line of attack frankly gets dangerously close to old canards about Jewish slaveowners. What you call Cyborg’s “whining, complaining and self-pity” is hardly an attempt to castrate him, it situates him in a much larger tradition of pathos-ridden outsider characters that’s firmly rooted in the Jewish experience. Superman, Spider-Man, the FF, the X-Men (both original teams), the Doom Patrol, Martian Manhunter, Orion, Silver Surfer. All created by Jews. These are figures who are exiled from their true home (usually after its destruction) or who don’t have a home to begin with, who fight to improve a world they feel despised by and know they’ll never fit into (tikkun olam), and who stand completely outside the current of human existence which the majority occupies. That sort of altruism in the face of radical alienation and exile is profoundly Jewish and I’d go as far as to say that American superhero comics wouldn’t exist today without it. It’s a narrative tradition that stretches back further than comics themselves (or even pulps, penny dreadfuls, dime novels and so on) to old Jewish folklore about tragic outsiders such as the story of the Golem of Prague.

Which isn’t to say that Cyborg’s always been well handled or that there isn’t a racism problem in comics. In the 80s and 90s especially there was a hell of a lot of extremely blatant tokenism when it came to minority characters. You only have to look at how hackneyed and offensive books like the New Guardians or JL Detroit are today to see that. But I do think that even during the Wolfman era Cyborg was a lot more genuinely post-racial than you’re realizing (certainly much more than his contemporaries like Luke Cage or Black Lightning). And I think erasing the historical ethnic context of American superhero comics is not only disrespectful to the creators but a very perilous slippery slope. This is a genre that was nearly entirely built on the immigrant and Jewish experience and painting it as a tool of white supremacy in a simplistic POC/white divide is reductionist, false and lends itself to bad actors.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Jewish and White are not mutually exclusive identities. Nor does the former identity somehow automatically exempt Wolfman or any other comics creator from the problematic representation of Black characters common to their work (at least at that time). It is that view that seems reductionist.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s this one scene in “God Loves, Man Kills” by Jewish writer Chris Claremont that this comment reminded me of. Kitty Pryde/Shadowcat gets into an altercation with a classmate of hers at ballet class after he starts spouting anti-Mutant remarks at her, calling her ‘mutie-lover’. Her teacher, Stevie Hunter, a black woman, talks to her after the fight and is given the line “they’re only words”, for the sole purpose of allowing the Jewish Kitty to snap back with “suppose he’d called me nigger-lover”. We’re supposed to side with Kitty here.

This is in a comic that opens up with the lynching of an (African-American) mutant family, and has a bigoted right-wing bible-thumping evangelist as the villain. It’s safe to assume that Claremont wasn’t trying to be offensive; rather, he was trying to reflect the internal tensions in this fictional universe; trying to make the harm done to this fictional minority feel real, feel raw. But did he run this idea by any black person before writing it? When a black man confronts Kitty with the word ‘mutie’ in Secret Wars II and she shoots back with ‘nigger’, did he run that by a black person? Did anybody who looks like me condone our people being used as strawmen so a Jewish woman can throw slurs at us in order to put emphasis on fictional bigotry?

My point here is that, while I’m not arguing against your presumption that comics reflect a historical Jewish narrative as communicated by dozens of Jewish writers over the years, that doesn’t mean that it reflects the narratives and lived experiences of other minorities, and may even overwrite them. Intersectionality be like that sometimes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Doom Patrol’s Unfinished Second Season Deserves Praise – Matt The Catania

Pingback: #13: Todo Lo Que Sé Es Que No Sé Nada, Y Ni Siquiera Estoy Tan Seguro de Eso | Nuclear

Pingback: Year-End Meta 2022: “Escaping Total Nullification” | The Middle Spaces