From a back-up story in Strange Tales #169, in which a white American businessman returns from Haiti with the knowledge of voodoo! And uses voodoo dolls to climb his way to the top of the corporate ladder. . . Or does he?

This the fourth in a series of posts about black superheroes that I started a couple of years ago. I’ve written about Marvel’s Black Goliath and DC’s Black Lightning, here on The Middle Spaces, and for Apex Magazine I wrote at length about Tyroc of DC’s Legion of Superheroes in the context of what afro-futures tell us about the present. This time I am exploring Marvel Comics’ Brother Voodoo—a character I feel really conflicted about. However, like all of these problematic examples, there is also something that makes me want to like him, to desire a way for the character to work without potentially offending a religious tradition and reinforcing stereotypes.

I should probably preempt this entire post to make the qualifier that I know very little about actual vodoun tradition, and am probably too familiar with its representation as Hollywoodized “voodoo”—stuff like The Serpent and the Rainbow horror movie (1988), and Roger Moore’s first go at being Bond, in Live and Let Die (1973). Len Wein and Gene Colan certainly worked to flip the usual script by making the voodoo practitioner the hero, but nevertheless, too much of the tension in the narratives that introduce Brother Voodoo is built upon the dark exotic danger of the “backwards” culture and its evil magic. The comic uses “voudoun” and “voodoo” interchangeably (mostly using the latter). I will be using “voodoo” to refer to the comic’s representation of magic and powers and spirits, and “vodou” to refer to the real-world practice of faith.

Brother Voodoo made his first appearance in a 5-issue arc in Strange Tales #169 to #174 in 1973 (an arc that found its conclusion in the magazine-format comic, Tales of the Zombie). His origin is told in the first two issues, and while on the surface the story may resemble that of Doctor Strange—skeptical doctor is forced to confront the magical and is trained by an old man who dies soon after training him to be the most powerful sorcerer ever—the story is complicated by the fact that Jericho Drumm, who is to become Brother Voodoo, is returning to Haiti after establishing his psychology practice in New Orleans. He has left behind the “superstitious customs” of his homeland. His brother, the supreme houdan (voodoo priest) of Haiti—are there even supreme Houdon, is there a national hierarchy?— is dying, the victim of a curse cast by Damballah, a self-proclaimed Loa (divine spirit) named for an actual one. From what I can tell, the comic book version of Damballah has little aside from the superficial in common with the Damballah of the vodou faith, and it is never made clear if he is supposed to really be one of these divine spirits, or as in the case of Mama Limbo—later in the series—is a fraud. One of the tensions in that first story is the suggestion that Jericho’s having left Haiti has undermined his racial/ethnic authenticity, and when they battle, Damballah mocks Jericho for having left to go to college and become a doctor, calling him a coward unwilling to face the cultural legacy of his family. By going through his ritual trials and having his dead brother’s soul inhabit his body to become Brother Voodoo, the comic doubles down on Jericho’s authenticity. It sutures two identities together. As Stuart Hall tells us, difference is constitutive of identity. In this case such constitutive difference is embodied by the superimposing the spirit of the brother who remained behind to follow a tradition frequently mocked and scorned beyond Haiti’s borders upon of the prodigal Haitian who left for America’s promise of betterment. There is possibility there—the character even inhabits a transnational space, moving frequently between New Orleans and Haiti, and in his later adventures in Brazil, tracing an Afro-Diasporic cartography—but the character never comes close to that potential. He even spits back Damballah’s mockery by sarcastically performing the patois the comic uses for all the Haitian characters (something that sounds more like fake Jamaican patois than anything like Haitian Creole), reinforcing his superiority to the “uneducated” around him despite having just been educated about his own ignorance of a very real spirit world his journey through higher ed never taught him about.

Brother Voodoo made his first appearance in a 5-issue arc in Strange Tales #169 to #174 in 1973 (an arc that found its conclusion in the magazine-format comic, Tales of the Zombie). His origin is told in the first two issues, and while on the surface the story may resemble that of Doctor Strange—skeptical doctor is forced to confront the magical and is trained by an old man who dies soon after training him to be the most powerful sorcerer ever—the story is complicated by the fact that Jericho Drumm, who is to become Brother Voodoo, is returning to Haiti after establishing his psychology practice in New Orleans. He has left behind the “superstitious customs” of his homeland. His brother, the supreme houdan (voodoo priest) of Haiti—are there even supreme Houdon, is there a national hierarchy?— is dying, the victim of a curse cast by Damballah, a self-proclaimed Loa (divine spirit) named for an actual one. From what I can tell, the comic book version of Damballah has little aside from the superficial in common with the Damballah of the vodou faith, and it is never made clear if he is supposed to really be one of these divine spirits, or as in the case of Mama Limbo—later in the series—is a fraud. One of the tensions in that first story is the suggestion that Jericho’s having left Haiti has undermined his racial/ethnic authenticity, and when they battle, Damballah mocks Jericho for having left to go to college and become a doctor, calling him a coward unwilling to face the cultural legacy of his family. By going through his ritual trials and having his dead brother’s soul inhabit his body to become Brother Voodoo, the comic doubles down on Jericho’s authenticity. It sutures two identities together. As Stuart Hall tells us, difference is constitutive of identity. In this case such constitutive difference is embodied by the superimposing the spirit of the brother who remained behind to follow a tradition frequently mocked and scorned beyond Haiti’s borders upon of the prodigal Haitian who left for America’s promise of betterment. There is possibility there—the character even inhabits a transnational space, moving frequently between New Orleans and Haiti, and in his later adventures in Brazil, tracing an Afro-Diasporic cartography—but the character never comes close to that potential. He even spits back Damballah’s mockery by sarcastically performing the patois the comic uses for all the Haitian characters (something that sounds more like fake Jamaican patois than anything like Haitian Creole), reinforcing his superiority to the “uneducated” around him despite having just been educated about his own ignorance of a very real spirit world his journey through higher ed never taught him about.

Damballah mocking Jericho Drumm as he beats him, thus motivating him to take on the training to become Brother Voodoo (from Strange Tales #169 – Sept 1973)

Vodou’s Damballah is one of the most important of the loa, associated with creation and with water and the rain. He is sometimes syncretized with St. Patrick (who drove out the snakes) and with Moses (who transformed his staff into a snake), and he himself is sometimes depicted as a snake. Most importantly, however, Damballah is a loving father figure. The Damballah of the Marvel Universe, on the other hand, is the black prototype for G.I. Joe’s Serpentor. Draped in snake cowl, he is physically strong and able to manipulate unspecified magical forces based on faith that lead to his enemies—in one example—to believe he has summoned a dragon to breathe flame on them, and thus they actually burn up! In fact, according to the Marvel way of things, vodou’s “magic” functions on belief. In order to defeat Damballah Jericho must do what his brother Daniel could not do, believe he could actually do it.

Marvel’s Damballah (left) and G.I.JOE’s Serpentor (right), cloned leader of Cobra, they have the same tailor.

I have no idea if this kind of system of belief is a part of actual vodou—a weakness of will leading to another’s beliefs superseding our own becoming a physical manifestation of the collapse of the ego and thus death—but there was nothing I could find in my admittedly limited reading on vodou that suggested such a thing. Furthermore, there is something about this characterization that I can’t help but connect to a prejudiced view of black people as superstitious and easily spooked by ”ghosts.” While magic in the world of Doctor Strange has its own weight and reality, the “magic” of the “voodoo” world as imagined by the House of Ideas remains ambiguous, if not right out fraudulent trickery.

Drumm’s power as Brother Voodoo, however, does manifest itself in concrete ways. His twin brother’s spirit is grafted to his body, giving him the strength of two men, and also allowing him to project that spirit to possess others and come to his aid. He is finally able to defeat Damballah by having Daniel’s spirit possess one of the would-be Loa’s henchmen to pluck the amulet that he uses to control snakes off his chest. Brother Voodoo then takes the wangal (a term that I assume is supposed to evoke “wanga,” a charm) and adds that power to his abilities, which also include the ability to remain unburned by fire. As the Strange Tales arc develops, he is depicted being able to control fire, and later to create it, but like a lot of depictions of powers in superhero comic books, the needs of the story determine the degree of power, rather than adhering to any consistent framework. In later appearances he is depicted being able to summon a mystic mist that he uses to teleport himself and others long distances, while in those first five appearances he simply appears mysteriously out of such a mist, always to unironic voodoo drum accompaniment. I don’t know if that last detail is the character’s most obvious and absurd racially caricatured feature, or if I should just admire Wein and Colan for their tone-deaf dedication to their troublesome representation.

Brother Voodoo’s comings and goings are accompanied by “voodoo drums” (from Strange Tales #173 – April 1974)

Much like Black Goliath and Black Lightning, there are things about the short-lived series that I enjoy and wish had been more developed. Brother Voodoo inhabits a world and community of black people, and these stories are among the few I can remember in mainstream superhero comics that had over 90% brown faces. The hero is black, the people he saves are black, the villains are black, and even when they aren’t black they are not all white—as Len Wein and Gene Colan imagined a global voodoo council that includes people from all over the world (including what looks like a Chinese Mandarin dressed in yellow) that had very few white faces, and none that stood out as more than background filler. In other words, to their credit, these stories in Strange Tales remain focused on the people from which the elements of the story arise, even if vodou itself is treated as just another set of myths from which to poach superheroic characters and concepts. And maybe it is just a source of mythic stories, I don’t know. I am not much of a religious person and take no issue when a comic incorporates elements of Judeo-Christian mythology—whether it is Lucifer in DC comics, or God and Jesus in Garth Ennis’s wildly overrated Preacher—so why should it bother me when it is just some other religion? I guess the difference is the difference between religious faiths with a huge influence in the world, and those that have been represented in ways that reinforce a project of hostile racialized dehumanization. And yet, I cannot help but like the idea of incorporating syncretic cosmological figures of incredibly adaptable and creative belief systems like Haitian and Louisiana Voodoo (and Santeria and whatever else) into the colorful superhero world. Why can’t we have Shango challenge Thor for mastery of thunder? Or Papa Legba join the ranks of the In-Betweener and the Living Tribunal. The challenge is how to accomplish such a thing without disrespecting a whole segment of people, who both earnestly practice these faiths and others who are associated with it through their ethnicity and blackness, and rarely to their benefit.

And yet, despite my own desire for something better, what is actually present in this comic is notably dim, especially the representation of Haiti. Whenever Brother Voodoo is called back to his homeland there is no sense of community or civic presence, just generic villages and nameless people, cultists, innocent villagers and villains. New Orleans is hardly any better, but at least there is some sense of civilization besides shacks and squalor. I understand that Haiti is an impoverished nation with a lot of problems, but it is too often represented as a kind of no-place—a vortex of disaster. I don’t know much about Haitian literature, though I have read a translation from French of Love, Anger, Madness: A Haitian Triptych by Marie Vieux-Chauvet, and a few books by Edwidge Danticat, like The Farming of Bones. Most of Farming of Bones takes place in the neighboring Dominican Republic, but even it evokes Haiti and Haitian identity as tragedy. It deals with the kind of anti-Haitian sentiment in the DR that Dominicans of Haitian descent are still dealing with. It seems that Haiti is still be being made to pay for having the audacity of overturning the slave state that once held it in bondage. And in a way, it is. Its history of external debt, for example, which fuels its ongoing struggle with poverty, began with France’s acceptance of reparations from Haiti to pay for the loss of property suffered by the French plantation owners when the slaves revolted. And yet, I resist that univocal narrative of Haiti as unending tragedy, even if I don’t know any other and cannot speak to them. For too many people, Haiti is synonymous with occult disaster, a darkness that implicates the blackness of its citizens for bringing it on themselves. The Brother Voodoo stories in Strange Tales do nothing to upset that.

When I think of Brother Voodoo’s diasporic possibilities, I can’t help but think of Fela Kuti’s fantastic song, “Zombie,” which uses the figures of the walking dead to critique the military power of his home Nigeria. In other words, it is possible to use the images of vodou to make a political statement that concerns the African Diaspora. Afrobeat injected Black American funk and jazz into Ghanaian/Nigerian High-life, and traditional West African chants and rhythms to create something that remained African while resounding in the Black Atlantic, echoing with a black identity rooted in what Paul Gilroy calls anti-anti-essentialism—“not simply a social and political category to be used or abandoned according to the extent to which the rhetoric that supports and legitimizes it is persuasive or institutionally powerful (see Spivak’s strategic essentialism)… [But] a coherent (if not always stable) experiential sense of self. Though it is often felt to be natural and spontaneous, it remains the outcome of [social construction].” The use of voudou in superhero comics, however, is essentially just exotic flavoring, elements of heterogeneous diasporic black culture as gimmick—kind of like Sam Wilson, the former Falcon’s recent transformation into Captain America. It is not just that white guys wrote and draw this stuff, but that they created something which is a mercenary sales ploy that ignores the subversive possibilities of re-envisioning American promise through the eyes of a black man (in the case of the Falcon) or an Afro-Diasporic consciousness that rejects a colonial mentality (in the case of Brother Voodoo).

It may be possible that whatever generosity I felt towards the character of Brother Voodoo emerges from the fact that by coincidence I also watched season three of American Horror Story, which in part dealt with voodoo, as I was reading these issues of Strange Tales. The show takes place in New Orleans and features a very weak story that also manages to not give a shit about the underlying belief structure they are representing. To the point of conflating Papa Legba with Baron Samedi (taking the former’s name for the latter’s likeness), which would be kind of like making a film version of the life of Jesus, but calling him John the Baptist because that name sounds cooler. The arc of Strange Tales that introduces Brother Voodoo doesn’t take quite the same kind of mix-and-match liberties, but has its own problems in that these stories repeatedly cast into doubt the reality of these figures within the comic book universe. Take for example, Marvel’s version of Baron Samedi.

Season 3 of American Horror Story’s Papa Legba is basically Baron Samedi by the name of a different Loa.

Baron Samedi is probably the most recognizable figure of voodoo. He is a Loa who is concerned with the dead and frequently depicted in a tuxedo coat with tails, a top hat, smoking a cigar and with his face painted like a white skull (or sometimes actually a skull). He dwells at the crossroads between the realms of the living and the dead, and is responsible for digging up the dead to transport them to the afterlife, and perhaps for leaving them trapped as walking corpses—the zombies of Haitian folklore who serve as slaves, sometimes depicted as serving bokor sorcerers. Baron Samedi is a disruptive figure. Lecherous and profane and has a love of rum. He is one of the most powerful of the loa and is married to Maman Brigette, a powerful Loa in her own right.

In Strange Tales # 171, Baron Samadi is drawn to wear a red military jacket with epaulets. He has a bald crown bordered by long white hair, and carries a staff topped with a skull. His face is drawn and colored to be marked by wrinkles and a bit desiccated, but is not skull-like—gone is his top hat and cigar. Rather than the more complex figure of vodoun faith, this version is a clear villain, responsible for a plague of zuvembies that have been reported in some local cemeteries on the outskirts of New Orleans where Brother Voodoo lives in a mansion helping those who seek him out, or when he notices disturbances in the world of the spirits.

But wait! Zuvembies? What the hell are those?

When the Comics Code Authority revised that code in 1971, they generally loosened up the restrictions on references to the supernatural, allowing for the depiction of vampires, werewolves and golems. At least part of the reasoning was that these creatures of folklore have a long European literary tradition, and thus if they are good enough for Bram Stoker or Mary Shelley they had to be good enough for comic books. However, the restriction was not lifted on the word “zombie” (which didn’t happen until 1989), because even as recently the late 80s as the mainstream comics industry was unconcerned with making their white supremacy blatant through obvious Eurocentrism. As a way to get around this, Marvel introduced “zuvembies,” creatures that appeared to be the walking dead, but that often have their origins not in the supernatural but in science fantasy. The absurdity of this banning of “zombie” is highlighted by the fact that since magazine format comics did not fall under the jurisdiction of the CCA, Marvel could print Tales of the Zombie in that format, so in theory the Brother Voodoo story that appeared in the magazine could have used the term “zombie,” but as it was no zombies or zuvembies appear in the Brother Voodoo stories in that mag.

Anyway, as the demands of the industry’s self-inflicted censor board required, Brother Voodoo’s face-off with Baron Samedi reveals that these are not true zombies, but rather living people put into a zombie-like state via technology supplied by A.I.M (Advanced Idea Mechanics). Brother Voodoo knew something was up when he tried to use the spirit of his brother to possess one of the walking “dead” and found he could not (I guess “science” is proof against possession). This plot point is fascinating for two reasons. Firstly, it is the first time that Brother Voodoo is explicitly tied to the rest of the Marvel universe through the Hydra-affiliated yellow bee-keeper outfit-wearing frequent Avengers foes A.I.M. (they are also referenced in Iron Man 3), and secondly how it puts contradictory forces to work in unison. A.I.M is a symbol of imperialist capital exploiting black bodies in a direct way with the help of old world stereotypes of voodoo blackness. What this plot also serves to do is to once again cast doubt on the actual divine power of yet another Loa (as was the case with Damballah and with later Mama Limbo).

The original Brother Voodoo arc was finished in the aforementioned black and white magazine Tales of the Zombie #6, wherein he defeats Black Talon, the son of the fake Loa Mama Limbo. He dons an out-of-this world black rooster costume, that is equal parts amazingly over-the-top superhero get-up and Richard Pryor in Stir Crazy. The black rooster is associated with a loa called Baron Kriminel, for whom they are sacrificed, but he is not mentioned in the comic magazine. The magazine itself is strange, since in order to qualify for magazine postal regulations, it had to include a certain amount of text. As such, Tale of the Zombie includes, in addition to other zombie-themed comics, articles like an overview of literature on voodoo in the form of a fictional conversation written by future X-Men scribe Chris Claremont and decorated with art re-purposed from the Brother Voodoo Strange Tales issues. There is also a feature called “The Voodoo Beat” which provides an overview of upcoming and (then) currently released voodoo-themed horror films and books, and claims, “Voodoo is alive and thriving (emphasis theirs) in the United States. Partially as a result of the growing number of immigrants from the Caribbean Islands…voodoo is spreading rapidly from household to household across the country.” The tone of the article is strange mix of alarmism about the influence of the occult, condemnation of the film industry’s “cashing in” on occult interest, and attempt to inform the consumer about the best of such fare to seek out. Regardless of the obscure location of the last episode of the Strange Tales arc, this is the end of the stories featuring Brother Voodoo as his own man, undertaking his own adventures, and not a guest star or sidekick to someone else.

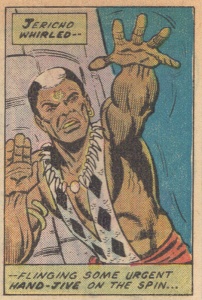

The thing is, that however problematic the original Brother Voodoo stories by Wein and Colan might be, the character was even more poorly served once he entered the stable of b-list characters available to make guest appearances in other titles. After Strange Tales (and Tales of the Zombie), Brother Voodoo next appears in four issues of Tomb of Dracula. He never gets to meet the Count, but essentially is part of the C-plot, where he plays magical Negro to Frank Drake to help him get his courage back fighting zuvembies in Brazil. Jericho Drumm would also appear in a four-issue arc of Werewolf By Night a couple of years later in 1976, helping the titular hero—aka Jack Russel—fight zuvembies commanded by Dr. Glitternight, a bald sorcerer in an inflated suit, floating around like a magic version of Baron Harkonnen from David Lynch’s Dune. Doug Moench writes Jack Russell as the kind of guy who makes casual racialized remarks in his narration of events in the panel captions. At one point he says something like “I hoped Brother Voodoo wasn’t talking through his afro,” when he doubts Drumm’s ability to take on the villain, and even more cringe-inducing, when he describes Brother Voodoo as “flinging some urgent hand-jive on the spin…” and later “mumbo-jumbo hand jive,” because nothing says evenhanded portrayal of a black character like a comparing his actions to his skill at dancing, or worse yet (given its origins) “mumbo-jumbo”—Ishmael Reed this ain’t. Still, the story is really out there and the few issues I bought just to read more Brother Voodoo stories have whet my appetite for more stories of Werewolf By Night. Before that, Brother Voodoo also made an appearance in a 1974 issue of Marvel Team-Up (featuring Spider-Man), which isn’t noteworthy save for the fact that Spidey takes to calling Jericho a very undignified “B.V.” and the fact that the cover depicts a white woman in jeopardy by the loa-possesed villain Moondog, but in the story itself the victim is a black woman.

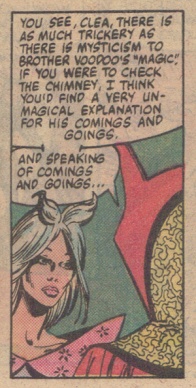

The most notable appearance of Brother Voodoo in the comics I own, is his appearance in Dr. Strange vol.2 #48 from 1981. Unfortunately, once again Jericho Drumm plays second fiddle to a white character. I mean, I understand that it is Dr. Strange’s title, and thus he is supposed to be the focus of his own stories, but to have Brother Voodoo show up just so that the ever-arrogant “Sorcerer Supreme” can defeat a returned Damballah who has possessed the spirit of Jericho’s brother and thus Jericho himself, through the “wangal” Brother Voodoo took from him way back in Strange Tales #170 is a severe injustice to the character. Brother Voodoo doesn’t even get to team-up to defeat his nemesis, but waits behind in Strange’s Greenwich Village home watched over by Clea and a servile Wong. Worst of all, at story’s end, Dr. Strange claims that Brother Voodoo’s powers are “as much trickery as they are mysticism.” In other words, he declares Brother Voodoo’s magic inferior to Strange’s powers, despite the fact that they have their origins in Orientalized notion of Far East mysticism.

According to Stephen Strange, Brother Voodoo’s magic (note the use of scare quotes in the panel) is “as much trickery as. . .mysticism.” (from Doctor Strange vol.2 #48)

After this Brother Voodoo made a handful of appearances in the late 80s and early 90s, but wouldn’t return as a recurring character until the middle of the 2000s, when as part of Tony Stark’s sell-outs he is pitted against The New Avengers, and eventually becomes Sorcerer Supreme and wielder of the Eye of Agamotto—changing his name to Doctor Voodoo. I haven’t read these, but the idea that Brother Voodoo would register with the government to chase down renegade superheroes is one that does not sit right with me. It seems like yet another injustice. I am happy to own his appearances through the 80s and ignore his being written to collude with colonial powers.

I guess it is probably also worth noting that Brother Voodoo appears in 2009’s Marvel Divas as an ex-boyfriend of Monica Rambeau (aka the former Captain Marvel and currently known as Spectrum), because I guess that being the only two black people of note in all of the Louisiana of the Marvel Universe, they have to date, much like Storm and the Black Panther had to marry because, you know, Africa. I haven’t read this series either, but I am increasingly curious about how bad they are, especially given my recent interest in romance comics.

“ONE OF THESE AVENGERS WILL DIE!” (I’ll give you a hint, it is one of the two black ones, and he’s not really an Avenger)

The last appearance of Brother Voodoo that I’ve read—I later got rid of the issues—is one of the most recent: 2010’s second volume of The New Avengers title, by Brian Michael Bendis. Drumm appears in the first six issues, but never joins the team, rather his sacrifice serves as a plot device to return to Doctor Strange the Eye of Agamotto and the mantle of Sorcerer Supreme. The most noteworthy part of this arc is that my wife, who knows very little about superheroes and nothing about comics correctly identified who would die based solely on the cover of issue #6—well, that and the fact that I informed her that Luke Cage was too important a character to die. The “black guy dies” trope resounds beyond comics.

I heard that recently he was revived somehow and is appearing in Rick Remender’s second volume of Uncanny Avengers, but uh…no thanks.

As much as I would love the version of Brother Voodoo I can imagine—one engaged with an Afro-Diasporic world of superheroes and mystic figures, enmeshed in a hyperbolic mythology that is developed as to not disrespect the belief systems of living people or give credence to stereotypes of threatening and savage blackness in the form of evil magic—I am not sure that character can exist. It just seems that the potential for Brother Voodoo to not feed into the fever dreams of the dominant culture is so limited as to be difficult to imagine it lasting even if such a series could ever get off the ground. Furthermore, it doesn’t help that Brother Voodoo has played second-fiddle to everyone since his introduction in the Marvel Universe, being mostly ineffectual or simply a method by which to bring in occult elements. As I’ve suggested before (and others have suggested more adamantly) the very idea of black superheroes is problematic given the genre’s white supremacist underpinnings, but I hold out hope that we, as discerning readers, especially readers of color, can transform our disidentifications into stories and characters of some depth and difference, as more of us are allowed to wedge our way into the industry, characters made noteworthy for more reasons than simply their pernicious racial encoding.

I really enjoyed reading your take on this Osvaldo. I read all of the original Brother Voodoo stories from the early ’70s (as collected in Essential Marvel Horror v2) sometime last year. I didn’t put as much thought into as you did, but I also got the overriding impression of a great deal of unused potential (and of course, the inevitable cringe-worthy moments).

Additionally, while nowhere near an expert on vodun/vodou and the related mythology, I also knew from somewhere that Damballah, or more correctly, Damballa, is generally considered a positive figure, roughly equivalent to Odin in many ways. Which is why I just have to give you a link to this: http://robmdavis.com/Airship27Hangar/index.airshipHangar.html#damballa

(Saunders is one of my favorite fantasy writers, and he really went to town with this story).

Also, I just can’t tell you how much I love that you linked Fela’s “Zombie.” That’s the first song by Fela I ever heard, and it’s still by far my favorite.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the link and for the response! My biggest wish for this blog, aside from guest posts, is for more discussion in the comments section!

LikeLike

Osvaldo, I appreciated your comments about the Brother Voodoo strip (and Hero for Hire, too, I suppose), specifically mentioning that it didn’t shy from having a cast of Black characters. But that leads me to wonder, in regard to many of the short-lived series you mentioned, such as Black Goliath, if Marvel had demographics to go along with their sales figures of the time. So when deciding to cancel a book, my guess is that it was only the overall bottom line that was considered, with little regard to percentages of sales in traditionally African-American communities, etc. It would be interesting to research those conversations, were they ever had. Did anyone care if a comic about Black heroes was catching fire among Black consumers, or was the only consideration of any importance the overall revenues or lack thereof?

Doug

LikeLike

Good questions! I don’t think Brother Voodoo or any of the other black superheroes were really meant to appeal to black readers specifically or draw that readership, but rather to appeal to white audiences for which stuff like blaxploitation and films like Live and Let Die had crossed-over/been appealing. This is not to say that there weren’t black comics readers, there were probably tons, but I doubt Marvel ever cared about fostering that market share in that era – nor did they care for sub-par stories and characters if they already were drawn to superheroes if they were white. To this day, I don’t think Marvel or DC has made the proper amount of effort for their black-led titles – drawing a big name artist/writer combo to do something interesting and actually give them the time to let it develop, like they have for other both big name and small-time niche titles.

LikeLike

I only had a couple of issues of Strange Tales that Brother Voodoo appeared in, and Tales of the Zombie magazine scared the crap out of me as a youngster, so I never saw him there. I dimly recall an occasional guest star role (one of which might have been that Dr. Strange tale you point out). My take on him as a kid, I think, was that he was a third-rate Dr. Strange, and I never warmed to him. Over time, I’ve come to be more interested in him, primarily from the angle of why was he created and how? It seems like it was purely to cash in on yet another perceived craze, the way Iron Fist was supposed to cash in on the kung fu craze, and Luke Cage was supposed to pull in fans of blaxsploitation -but do you think there was any serious effort to really develop a book for Black readers? I’m also curious if the portrayal of Vodou got any better when the character was revived recently and made an Avenger.

LikeLike

I think the answer to your two questions are no and no – unfortunately. I think only DC made an effort by backing/distributing Milestone in the 90s – but even that was a mostly failed experiment. See my response to Doug on my feelings about how the Big Two have handled black characters. I mean, they have never really looked to give the kind of support of a big name and big marketing push for a black character – even the new Sam Wilson Captain America is being written by a comic writer with a history of poor idea about representations and poor reactions to critiques

LikeLike

Since I have the complete run of Tales of the Zombie as well (yep, Marvel Essentials again), I can confirm the point Osvaldo made about stuff like Brother Voodoo or Zombie/Zuvembie stories being published mainly to appeal to white audiences interested in the subject from other media (i.e., the movies). The text pieces definitely confirm this – I don’t feel like pulling the book out right now, but as I recall there was an article in the first or second issue that “explains” voodoo, by renowned anthropologist, ethnographer and religious studies expert Chris Claremont (o.k. maybe I’m being a little too mean; as I recall, he read up on the subject and did shine a hard light on the Atlantic slave trade and hardships suffered by the Haitians before and after they gained independence), while in most of the other issues the text pieces, sometimes also written by Tony Isabella, mainly dealt with the various movies that featured voodoo and/or zombies.

And Karen, I can relate to your fear of horror comics as a kid: I hardly ever touched them back then – they also scared me. Before I hit my teens, I think the only horror comics I ever read were two or three issues of Swamp Thing and an issue of Tomb of Dracula, both belonging to friends. Funny, though, when I did read a bunch of those “horror” titles as teen, and much later as an adult, I realized the stories are all pretty tame, i.e., not every horrifying at all. In the aforementioned Essential Marvel Horror book, the stories featuring Gabriel the Devil Hunter were the only ones I found somewhat unsettling (and they probably would have really freaked me out if I had read them as a preteen attending a Catholic school). And the art, by Sonny Trinidad, captures the macabre feel of the stories perfectly.

LikeLike

Thoroughly enjoyed reading the post.

One of the text pieces Edo referred to – in this case a behind the scenes about creating Brother Voodoo – has been posted at

http://www.diversionsofthegroovykind.blogspot.co.uk/2012/10/black-and-white-wednesday-introducing.html

Inauthenticity isn’t too much of a difficulty – I don’t know that Fela needs to demonstrate a nuanced understanding of Haitian myth for Zombie to be pretty great – but those remarks about “poor mans magic” are, to say the least, unfortunate and give a pretty good insight into why the comic was going to have problems. Which you sum up well.

On the other hand though…. I recently read the first couple of Strange Tales appearances for the first time since I was a kid, and was surprised they weren’t a lot worse (maybe I just want to like them too). The credit for the extent to which they do work must surely go to Gene Colan. I’m not trying to make a “nice art” excuse, but rather argue that the images carry meaning as well as and alongside the writer’s text. And sometimes work in a different way…?

You’re right about how Brother Voodoo inhabited a world of black people (the only other superhero comic I recall like it from that time is Jungle Action/ Black Panther) and Colan really brings that to life in a way that few Marvel artists of the time could. Romita’s cover for ST 169 for instance, screams Blaxploitation formula whereas Colan’s more subtle realism works against that (although he still has to work inside the editorial brief so can’t escape it of course)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi sean!

Oh man! That is a great resource! I need to add that to my list of things to pick up – I can’t believe I missed it in my research.

I think you are right that Fela did not need (and probably did not have) a nuanced understanding of Voudon to write “Zombie,” but just by virtue of his using the idea of zombies to critique his own nation’s institutions of power (the military), rather than as something resulting from a representation of blackness tied to evil and primal occult forces speaks to the degree to which simple framing can deeply influence attitudes.

I agree that Colan’s art is great.

One of these days I should write about what I find to be an overrated run on Jungle Action. . but you are right, it too depicts a black world -I just take issue with the depictions of the average Wakandan in relation to the supposedly technologically advanced state the nation is supposed to have. More than once it makes it seem like the “natural disposition” to superstition makes African people reject the possibility of progress.

LikeLike

Pingback: “I Know It When I See It”- Race, Relatability, and Reading Practice | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Do Zombie Lives Matter? Fear the Walking Dead & Zombie Politics | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Recommended: Adilifu Nama’s Super Black | the becoming radical

Pingback: Additions, Corrections, Retractions | The Middle Spaces

Brother/Doctor Voodoo has long been a character that interested me, which is what eventually led to me buying and reading the trade paperback for “Doctor Voodoo: Avenger of the Supernatural”, penned by Rick Remender. While your dislike for him is well-documented it is worth noting that the writer has strongly championed for the character, pitching the aforementioned limited series, resurrecting him near the tail-end of his “Axis” event [undoing his demise at Bendis’s hands], and then choosing to include him in his “Uncanny Avengers” [which consequently led to him continuing to be a part of the team currently written by Gerry Duggan].

Speaking of Bendis, it’s also interesting to consider that one of the reasons Luke Cage has risen to prominence in the comics [prior to him being slated to receive his own show on Netflix] is due to the attention he paid the character. That of course also connects back to what Colan and Wein were doing with “Brother Voodoo”. While the comic book landscape is currently changing, particularly in regards to creators, I think there’s a conversation worth having about the White creators and the characters of colour [big ups to Moench for all he did for Shang-Chi] that they were truly passionate about.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Evan! Thanks for stopping by and extra thanks for commenting (as I said above, one of the things I want more of for this blog is more conversation in the comments).

I made a conscious choice to stop my collecting of Brother Voodoo comics with his appearances in the 80s b/c after reading his treatment in New Avengers (vol. 2) I was just not interested. And I will admit that my feelings about Rick “Hobo Piss” Remender didn’t make me reconsider that when I heard he’d been revived. That said, I would still read those books, but need to find them in the library or grab them from a friend, as I’m not willing to pay for what I fear I would be disappointed in.

I think you make an noteworthy point about the black (and other PoC) characters who have had a success/revivals because of the efforts of white writers, and I think it is one worth looking into. However, I remain skeptical about the results regardless of the intent. I think Bendis’ rebirth of Spider-Woman (Jessica Drew) is a perfect example of the dissonance btwn intent and result (I bring it up in a post about the new SW series), because I had the yucky feeling he was bringing her back b/c she was sex fantasy-favorite of his youth. I finally find SW interesting in the current series for the first time since her original series. I also mention a bit about the way white readers identify with fave PoC characters in my post entitled, “Race Relatability and Reading Practice.” That said, I am all for writers of any ethnicity pushing and supporting more characters of color as long as they are represented beyond a stereotype.

I plan to read more of your Culture War Reporter site, and I hope to see you around here more as well. Cheers!

LikeLike

Pingback: The International Comics Art Forum 2016 | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Report on ICAF 2016 | Comics Studies Society

Pingback: Marvel Five-in-One: Prominent, Notorious and Invisible Black Lives of the Marvel Universe | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Mo’ Meta News: How Collecting Shapes The Middle Spaces | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: On Collecting Comics & Critical Nostalgia | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: The (re)Collection Agency #13: A Conversation with Anna Peppard | The Middle Spaces