This week’s post is a part of SUPER BLOG TEAM-UP. SBTU is a loose affiliation of comics-related blogs that all simultaneously post on a theme and link to each other’s work a few times a year as a way to build awareness about other blogs and demonstrate a variety of perspectives on our favorite medium. This the fourth time Super Blog Team-Up has happened and the first time The Middle Spaces was invited to take part. I was honored to be asked, especially since I already follow a number of the blogs that participate and because I think the perspective of this blog is fairly different from the others. Nostalgia has its place, but we here at The Middle Spaces aim for critical nostalgia. Be sure to check at the end of the post for links to the other participating blogs.

The theme for SBTU #4 is the team-up itself. Most folks went the way of the unusual or “wacky” team-up, but rather than examine a wacky or uncommon one, I’ve chosen a fairly common team-up (Spider-Man and Daredevil) that upon further scrutiny plays out in an unusual way—it uses two superheroes frequently thought of as “street level” (a designation that stands in opposition to the global, the cosmic or the occult) in a way that comments on the narrative of street crime and the criminal in the United States, and highlights a conservative turn in the social fabric that arrived with the Reagan Era.

Issue #107 begins with a flashback to Jean DeWolfe’s life, leading to this bloody panel. We learn about her potentially interesting backstory just before we learn she is dead (from PPTSSM #107).

“The Death of Jean DeWolfe” is a 4-issue arc of Peter Parker the Spectacular Spider-Man from 1985, written by Peter David, with pencils by Rich Buckler. Despite its name, the actual death of no-nonsense female police captain Jean DeWolfe is beside the point, except that she serves as yet another example of the all-too-common “women in refrigerators” trope in comics. While her death gets the action started, the popular supporting character was offed mostly as a way to make Spider-Man particularly motivated to find her killer (as if he really needs an excuse, seeing as he is a superhero who has been known to spend time tracking down the killers of people he doesn’t even know). In addition, in case their professional relationship (established since her first appearance in Marvel Team-Up #48 from 1976) was insufficient to motivate him, during the course of his investigation Spider-Man finds a bunch of photos and news clippings featuring him in her apartment. Is she doing detective work, trying to figure out who Spider-Man might be? Is it a scrapbook of cases she worked with help from the superhero? No. She is a secret Spider-Man fan-girl who is crushing on the superhero, a point reinforced by the fact that she cut the Black Cat out of some of those pics, like a jealous teenage girl wanting to get rid of Kristen Stewart’s mug in order to better imagine herself next to Robert Pattinson. Spider-Man is suddenly all the more driven to find her killer, touched by her secret obsession. It is a disappointing end for an interesting character. David claims her death was editorially mandated by Jim Owsley, but whoever’s idea it was, it sucks.

The plot of “The Death of Jean DeWolfe” is not that important to my examination here either. You can read a fairly good overview of it here, but essentially it involves the hunt for a hyper-violent vigilante called “Sin-Eater” who runs around with a shotgun and a green ski-mask killing people he accuses of being “soft on crime”—a motivation that doesn’t even hold up considering that Jean DeWolfe was anything but soft on crime. Some years later another writer would ret-con a romance between DeWolfe and Stan Carter, the police detective who would turn out to be the Sin-Eater, as a way to retroactively give him a motivation, but as far as anyone knew in 1985 he was just an ex-SHIELD agent driven mad and given bursts of inhuman strength by the side effects of being the subject of an experimental PCP derivative to make super soldiers.

The plot of “The Death of Jean DeWolfe” is not that important to my examination here either. You can read a fairly good overview of it here, but essentially it involves the hunt for a hyper-violent vigilante called “Sin-Eater” who runs around with a shotgun and a green ski-mask killing people he accuses of being “soft on crime”—a motivation that doesn’t even hold up considering that Jean DeWolfe was anything but soft on crime. Some years later another writer would ret-con a romance between DeWolfe and Stan Carter, the police detective who would turn out to be the Sin-Eater, as a way to retroactively give him a motivation, but as far as anyone knew in 1985 he was just an ex-SHIELD agent driven mad and given bursts of inhuman strength by the side effects of being the subject of an experimental PCP derivative to make super soldiers.

Damn, but do superhero comics get convoluted fast…and that is just the beginning—Peter David wrote a mess of a story. It might be considered a classic by many Spider-Man fans, but there is no arguing that David was an amateurish, if ambitious, writer at the time (this was only the second story he sold to Marvel). He threw in a mess of themes and characters in an attempt to create a sophisticated and dark Spider-Man story. And I will admit, at age 13-going-on-14, I was impressed. The grim and dark tone of the story appealed to my sense of what was adult and topical. The conflict between Spider-Man and Daredevil and their disagreement about the best way to deal with criminals was compelling at that age. I had never considered super-hero team-ups could work that way. In my experience up to that point, I knew of the common trope of superheroes mistakenly fighting before teaming up to tackle the real danger, or the occasional mind-control plot (as in their first meet-up back in 1964’s Amazing Spider-Man #16), but the idea that there could be an on-going conflict between two closely related heroes was new to me.

Re-reading it now, the most amateurish aspect to the story is how sloppily David curtails Spider-Man’s abilities to make sure that the non-superhuman Sin-Eater cannot be caught and to make the fights with Daredevil (as super-strength of any degree is not in his power set) more even. More than once, despite all his experience fighting bad guys, Spider-Man is so flustered he fights poorly. At another point both of his web-shooters happen to have been broken when he goes to web the Sin-Eater and halt his escape. Later, in the most ridiculous example of David not knowing how to best write the characters within their abilities, Spider-Man is so “emotionally worked up” while fighting Daredevil he collapses into unconsciousness like a child after a tantrum, giving ole hornhead a chance to escape. I guess, a generous reading would connect such a failure of Spider-Man to live up to his powers to the precedent set way back in Amazing Spider-Man Annual #1 (1967) when his powers seem to dry up when faced with the anxiety of facing the Sinister Six, but really that was the weakest part of that surprisingly weak issue, as well.

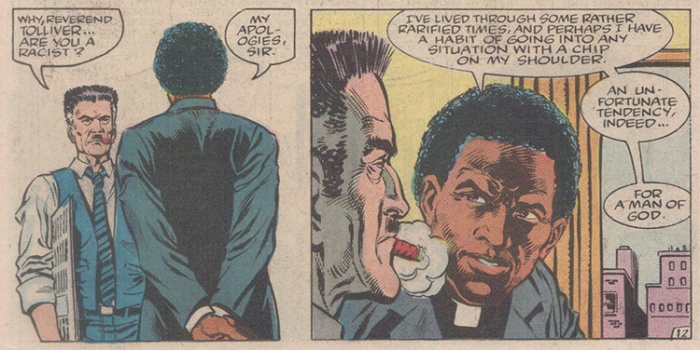

The mess of the Sin-Eater arc, however, emerges mostly from David’s attempt to squeeze in every possible reference and character he can in an attempt to explore the crime-ridden era. There is a sub-plot involving Ernie Popchik, a resident from Aunt May’s boarding house for the elderly. Outraged, that some random punks who robbed and beat him up were released on their own recognizance at the behest of star defense attorney Matt Murdock, he later shoots some teenagers on the train Bernie Goetz style. There is the death of Jean DeWolfe itself, which comes at the end of a two-page flashback of her whole life, and even a panel where Charles Bronson (of Death Wish film series fame) is depicted holding up a newspaper that reads, “Vigilante Strikes Again.” There is a Sin-Eater copycat who bursts into the Daily Bugle newsroom. And finally, there’s a recently arrived black clergyman from the Atlanta area, Reverend Jackson Tolliver, who makes frequent reference to the 1980 child-killings in that city and the failures of the police to do much when the victims of crimes are black. He is mostly depicted as a political rabble rouser—an Al Sharpton-type phony who lives for publicity and who in one panel is inexplicably depicted with a white blonde woman on his arm. The only role I really seem him playing in the narrative is to give J. Jonah Jameson a chance to accuse him of being racist. It is the classic attempt to make the activist who observes racial inequity seem like bad guy for pointing out the obvious ways that white supremacy works in our society. David goes so far as to make Tolliver apologize to Jameson for having “a chip on [his] shoulder.” This reference to race is particularly jarring because the story takes place in a Marvel Universe that never addresses the role of race in representations of criminality, where the problem of how superhero comics depict urban crime arises.

As I have obliquely suggested in past posts, superhero comics, and especially superhero comics of this era, inhabit this strange site where they most often visually represent criminals as white, but still use the coded language that suggests the equation of blackness to criminality. The first example in the “The Death of Jean DeWolfe” is probably the fact that while the rough youths that beat up Mr. Popchick are drawn to look like generic punks with cut-off sleeve vests, mohawks and bandannas, Peter Parker refers to them as “animals.” While this may be tenuous evidence, it is certain that bestial comparisons are a common form of racial encoding. Furthermore depicting them as some kind of punk rockers is an attempt to denote difference without resorting to the potentially offensive racial difference. The much more obvious example, however, is later, when Popchik shoots his would be muggers on the train. The scene is clearly meant to evoke Bernhard Goetz’s 1984 shooting of four black youths—to the degree where one of them very politely, if disingenuously, asks the man for money (echoing the claim by Goetz’s alleged would-be attackers that they were panhandling, not mugging). These three white shockingly flamboyant young men in tight pants and cut-off shirts are all white, and yet the real-life story the scene conjures is among the most racially charged in recent New York history. These punk rockers (or whatever they are supposed to be) become a way for superhero comics to attempt to remain relevant by addressing a contemporary issue—the problem of rampant crime in American urban centers in the 1980s—without becoming enmeshed in the mess of racial politics that comics have a notoriously awful track record in handling. I can understand Marvel Comics wanting to avoid the obvious reinforcement of some kind of essential black criminality, but through their whitewashing they nevertheless accomplish the same result through sleight-of-hand. Let us not forget that it was reported in New York Magazine that prior to the shooting Goetz made public comments along the lines of “The only way we’re going to clean up this street is to get rid of the spics and niggers,” and yet there were plenty in New York City who hailed him as a hero.

Let me put it as clearly as possible. The muggers in these Marvel Comics obsessed with urban crime of the 1980s may be drawn to appear white, but when the reader experiences a catharsis by reading about these street-level superheroes cleaning up the streets, what is being evoked is the narrative of black criminality echoed by white politicians and the media.

This notion is aided by the lack of nuance in comic book morality. The generic bad guys, from street muggers to super villain henchmen are just bad guys. They are people who have chosen to partake in criminal activity due to a moral failing. Period. While I am not arguing that people aren’t ultimately responsible for their choices, the reactionary basis for the superhero genre is that state power is insufficient to defend the populace against rampant crime. The failing of state power in this schema is not that state power fails to justly and fairly apply the law or to address the social and economic conditions that lead to crime (which for the most part is perpetrated by people in their own communities—both black and white), but not being tough enough on criminals. All the support Bernhard Goetz received after the shooting brings to light the conservative “tough on crime” turn in America. A turn undergirded in those years by the thinly-veiled racial politics of the Reagan Administration and its focus on “welfare queens” and the War on Drugs, even as the CIA was involved in cocaine-trafficking in Central America, smuggling it back into urban centers and fueling the depredations of the Crack Age. It’s as if Goetz were the living embodiment of that old joke that a Democrat is just a Republican that hasn’t been mugged yet.

And this finally brings us to the team-up of Spider-Man and Daredevil. It is actually not much of a team-up at first. The two never even cross paths in their superhero garb until the third issue. They meet as civilians in the first issue (#107), but this is the story that sets up their knowing each other’s secret identities, with Matt Murdock recognizing Peter Parker’s heartbeat as Spider-Man’s in the courtroom, but the latter not knowing that Daredevil and Murdock are one and the same until the end of the final issue of the arc (#110). What makes this team-up so unusual is that for over two and a half issues, Spider-Man is always one step behind Daredevil in investigating the Sin-Eater murders. When Spider-Man visits Kingpin to learn what he can from the underworld boss, he finds out Daredevil had already been there. When Daredevil goes to ask questions at a seedy bar patronized by shady characters in civilian guise knowing that as a superhero he is less likely to get information, he is interrupted by Spider-Man smashing through the window to intimidate and brutalize the patrons. Actually, throughout this story Spider-Man is a brutal and reactionary figure. He beats on muggers that surrender, humiliates a man in front of his young daughter, and argues vehemently against how “easy” the courts are on criminals, and has no respect for their rights. Peter David uses Spider-Man as the voice of the typical working class white American whose call for courts to be “tough on crime” resonates with a racial resentment. He has to be physically pulled off Sin-Eater by Daredevil when the killer is finally confronted to keep the friendly neighborhood Spider-Man from beating the man to death. This is a Spider-Man who is frighteningly a lot like the Doc Ock-possessed Superior Spider-Man I wrote about in August. Later, he even is willing to let an angry mob lynch the man, and only intervenes because Daredevil who is trying to protect him is overwhelmed and in danger of being badly beaten himself.

Daredevil’s coming to Sin-Eater’s defense is, of course, in line with Matt Murdock’s civilian job as a defense attorney. In those two final issues, David uses Daredevil to argue against Spider-Man’s vigilante tendencies and to make a connection between his disregard for due process and the Sin-Eater himself, whose crimes are extreme vigilante acts against those he deems sinners for their defense of criminals. The judge who is killed was the one who let Popchik’s attackers go on their own recognizance, and the priest who was killed was against the death penalty. He seeks to kill J. Jonah Jameson for his anti-Spider-Man editorials. Spider-Man’s argument against this comparison is essentially to say, “But I’m a good guy.”

Brought together in this story, Spider-Man and Daredevil demonstrate a hegemonic framework for understanding urban crime. They are the range of dominant cultural/political context for understanding “normal” (i.e. non-super-powered) crime in their comic book universe, as such reflect an acceptable range in our own world. Spider-Man is the violent reactionary; the working class type who wants cops to be tough on crime because he buys into a narrative of crime that divorces criminal acts from social and economic contexts, turning a blind eye to how that increasingly strident position can turn against him. In his role as superhero vigilante, Spider-Man toughens up his own approach. Daredevil, on the other hand, represent the bourgeoisie white liberal who believes in the system, and feels that everyone should get their fair day in court. The story even ends on that note, with Matt Murdock offering to find help for Mr. Popchik, who like Bernhard Goetz turns himself in, but faces criminal charges for shooting those kids on the train. As Murdock says to Aunt May, “I’d like to prove to your nephew here that the system works.”

And yet, Murdock’s need to go out at night in a horned cowl and red tights and beat on people in Hell’s Kitchen with a billy club is evidence that the system doesn’t work through his frequent violations of it, both inside and outside of the courtroom. He enacts the alternative to not submitting to sanctioned and organized state violence—implicitly sanctioned individual violence by members of the dominant culture. These two-sides, presented as if both are reasonable responses to the admittedly very high crime rate of 1980s New York City do not represent the breadth of perspectives on the issue. There is no suggestion here that the system does not work not only for the myriad ways that its legal protections are not applied fairly, but because of the social conditions that lead to the concentration of crime in marginalized and heavily policed communities. We are nearly 30 years on from “The Death of Jean DeWolfe” story, but Ferguson, Missouri, for example, is evidence that despite the national drop in crime rates, “the system” that Matt Murdock puts so much faith in does not work—or perhaps works too well when viewed as purposefully designed towards the goal of mass incarceration. To a kid reading that comic in 1985, or even an adult reading it now with nostalgic eyes, the story seems edgy for its willingness to present “both sides” and put these heroes in tension, but the very idea that there are “two sides’ is a lie—there are no sides, just a swarm. One of the most frequent truisms my students regurgitate into their essays and class comments is how “there are two sides to every story.” The notion of “two sides” is a framework that says you may only legitimately imagine the world between these poles, anything beyond is insanity, impractical, unimaginable.

At least in the current Daredevil series he struggles against the Sons of the Serpent, a white supremacist group that has deeply infiltrated and controls the justice system in New York. Yet even that is misleading, for while it may suggest injustice through a fictional cultish organization, in reality there is no need for the dominant culture to even believe it is participating in such a cult in order to be complicit in it. This series of events leads to the outing of Daredevil’s identity and his (well-deserved) disbarment in New York state, so I appreciate Mark Waid’s exploration of the problems inherent to Murdock’s dual role, yet Daredevil remaining “the hero” underscores the exceptionalism under which the superhero operates, the very premise of the character remains problematic.

Returning to “The Death of Jean DeWolfe,” it may be possible that Peter David’s inclusion of the Reverend Jackson Tolliver character serves to highlight the dissonance between the white-washed representation of urban crime in comics and the reality of the time. I mean, it certainly seems strange that for the first three issues of the arc Tolliver is making a stink about the treatment of black people when there are no black people whatsoever in the story aside from him, the priest that Sin-Eater kills, and the always respectable editor-in-chief of the Daily Bugle, Robbie Robertson (Tolliver does not appear in the fourth issue), but looked at in combination with his representation as a publicity-hound, all this does it reinforce the idea that activists and those concerned with social justice are just “seeing things as racial” when they really aren’t—conveniently ignoring the fact that what he says about police, the justice system and the criminalization of blackness are 100% true.

I also want to add, that as I look over this story-arc and what I have written, I may have been too quick in dismissing the role of Jean DeWolfe in this story named for her. As I have tried to argue about the absence of black criminals commenting on the fraught nature of the discussion of urban crime, so too does the absence of DeWolfe in the story of her death suggest something about who gets to determine what is important in this framework and how it will be important. In other words, there is a paternalism at work that not only resounds in how the white characters get to decide how the idea of criminal justice is framed, but the kinds of violations that represent the worst kinds of crime—those against women—not because of the victims themselves as people, but in their relationships to men.

As I mentioned before, Jean DeWolfe’s professional connection to Spider-Man is deemed insufficient for this story and so it is juiced up with the suggestion of a more personal desire for Spider-Man, as to make her death seem all the more tragic. It is not the loss of Jean herself that becomes central, but the loss of some future deeper connection to the male protector, who having failed at protecting, becomes the instrument of justice. Similarly, the cliffhanger between issues #109 and #110 (the 3rd and 4th issues of the arc) hinges on the possibility of Sin-Eater having killed Betty Brant. Marla Madison (J. Jonah’s wife) is also in peril. Issue #110 opens with Peter Parker/Spider-Man rushing to the scene of Sin-Eater’s attack but replaying his relationship with Betty in his head. We the loyal reader of two decades of Spider-Man (at that point) are reminded why Betty is important through her importance to the story of Peter Parker. She is able to fight off Sin-Eater long enough for Spider-Man to arrive, but once he does she only serves to react voicelessly to Spider-Man’s brutality. She is just an instrument of the plot, not a character.

Betty Brandt made Peter Parker feel like a man. It sure is a shame she might be dead! (from PPTSSM #110 – click on image to see more)

Later, Betty is interviewed by a TV journalist in order to set up the portion of the plot where the news gets out that Sin-Eater is a cop and a mob forms to dish out vigilante justice and make up for the apparent shortfall of state power. They are meant to demonstrate the potential dangers of the vigilante superhero in their attempt to do what Daredevil kept Spider-Man from doing. This mob forms without even knowing that it is likely that Sin-Eater will get off with an insanity plea and not do any jail time due to his having been the subject of SHIELD experiments—something the cops express will underscore their ostensible impotence even more (even as it suggests that people that suffer from mental illness are somehow “getting away with something”). As such, Daredevil’s trust in the system is put on shaky ground and the reader is left to wonder, who is right between these poles of street level heroes? The answer must be “somewhere in the middle,” without considering that hegemony controls where the goalposts go. It is a theme notable in a run of Spider-Man comics of the era, including the introduction of the anti-heroes Cloak & Dagger, who track down and kill those responsible for making and selling the drugs that killed dozens of runaways like them, the “Gang War” arc that also features a conflict between Spidey and Daredevil about how to handle the criminal underworld, and multiple appearances of the Punisher, Spider-Man occupying whatever necessary moral position to maintain the status quo.

Ultimately, these four issues of Peter Parker, the Spectacular Spider-Man are not “All-New All-Daring,” as their covers claim, but rather they reinforce how the mainstream is so limited as to partition reality into a box—to call it “real” and still ignore the obvious. It is the manipulation of a cognitive dissonance. “We allude to the real as to give our stories gravity, but when challenged on the implications of that ‘realness’ we can still claim it is a made up story.” Here is the great trick: the allusion to the grim and gritty aspects of life—the stuff that supposedly lends these comics a sense of “reality”—to create a race-neutral fantasy that allows narratives of crime to appear politically neutral. The story remains “balanced.” They have told “both sides.” We, the readers, can work it out to reach a safe conclusion from there. Meanwhile, the discourse shifts right, increasingly perniciousness, so that even ostensibly liberal figures whether they are fictional like Daredevil or historical like Bill Clinton, are mere stand-ins for a “moderate” stance that is anything but. . . Consider the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, signed into law by Clinton (dubbed by the overly-credulous as “our first Black president”), which enacted policies built on Reagan Era narratives of criminality that not only over-incarcerate black and brown citizens, but make sure it is as difficult as possible to work towards rehabilitation or foster prevention. By its very nature, a frame not only encloses what is included, it chooses what to exclude in its representation, and as such can claim ignorance of how addressing what is in the frame affects what only appears to be absent.

Super Blog Team-Up #4 Round-Up!

1. Super-Hero Satellite: Super Man and The Masters Of the Universe

2. LongBox GraveYard: Thing / Thing

3. Superior Spider-talk: Spider-Man and the Coming of Razorback!?

4. The Daily Rios: New Teen Titans/DNAgents

5. Chasing Amazing: Spider-man/Spider-man 2099 Across the Spider-Verse

6. Vic Sage/Retroist: Doctor Doom/Doctor Strange

7. Fantastiverse: Superman/Spider-Man

8. Mystery V-Log: The Avengers #1

9. In My Not So Humble Opinion: Conan /Solomon Kane

10. The Unspoken Decade: Punisher/Archie!!

11. Flodos Page: Green Lantern and the Little Green Man

12. Between The Pages: World’s Finest Couple: Lois Lane and Bruce Wayne

13. Bronze Age Babies: When Friends Like These ARE Your Enemies

Note: These blogs update at different times, so if you click on one of these links and they lead to a 404 error or an un-updated site, try again in a few hours.

Pingback: Thing Vs. Thing! | Longbox Graveyard

This was a very interesting, thoughtful analysis. You definitely raised some very valid point and gave me a totally different way of looking at this story.

I think a somewhat better attempt to analyze the question of due process vs vigilantism was done by Ann Nocenti a couple of years later when she wrote Daredevil #249, which saw DD arguing out the question with Wolverine. DD wants to bring in the anti-mutant assassin Bushwacker to face trial for his crimes, and possibly to get help for his psychological problems. Wolverine, not surprisingly, wants to kill Bushwacker. The two of them quickly come to blows over their very different ideologies. It is a bit heavy-handed, but I think Nocenti did a fair job with it.

LikeLike

I think these stories are the result of when comics companies try to be “relevant” but remain uncontroversial – they end up failing at both.

Thanks for commenting!

LikeLike

It is the rare comic that can impress the same way today as it did when we were kids — at my own blog, my very first post was about how the “Golden Age” of EVERYTHING is, “twelve” — but comic stories earnestly trying to tackle burning issues of their day usually age worse than others. The Adams/O’Neil Green Lantern/Green Arrow run is rightly remembered for tackling taboo subject matter but I find it tough sledding as a re-read. Would like to see you place that series under the same lens you’ve applied here!

(And likewise for Steve Gerber’s work at Marvel in the early 1970s).

LikeLike

Maybe one day I will get my hands on those GL/GA issues – I would LOVE to (every book of comics scholarship that even touches on superheroes mentions that infamous, “yellow people, blue people, but not the black people” speech – or however it goes), but right not they are out of my price range for what I spend on comics.

At least they tried to address race in a direct way, though yes, I am sure it is cringeworthy.

Thanks for commenting! I haven’t gotten a chance to read your contribution to SBTU #4 yet (starting a new job is kicking my ass), but it is on deck for the weekend.

LikeLike

DC reprinted the whole O’Neil/Adams Green Lantern/Green Arrow run in 1983 (imaginatively titled, “Green Lantern/Green Arrow”) — you can scare up those reprints on the back issue for less than five bucks each. It was seven issues total, each (I think) reprinting two books from the run. They’re worth having.

(And don’t expect much from my SBTU entry aside from a couple lumpy dudes hollaring, “It’s Clobberin’ Time!”)

LikeLike

Pingback: Spider-Man and the Coming of Razorback!? | Superior Spider-Talk: A Spider-Man Website

Pingback: Two Wrongs Making a Right-SBTU-Punisher Meets Archie! | The Unspoken Decade: 90's Comic Book Blog Extraordinaire

Sorry for not commenting sooner – I’ve been working through a bunch of these “team-up” posts, and well, hell, I have a life outside of reading and commenting on comic blogs.

Never read this particular story, because by the time 1985 had rolled around I was in a phase where I had pretty much dropped all of my comics reading, except for a lingering loyalty to the X-men.

Judging by your summary, it sounds like a hot mess; personally, I always thought Jean DeWolfe was a really cool character that should have eventually become something like Spidey’s Commissioner Gordon. It’s really too bad that she was killed off. Also, the idea that she was secretly pining for Spider-man? Uggh.

Anyway, great post – and much food for thought – as usual. And man, I so agree with your critique of that “two sides to every story” cliche…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, I had forgotten about the secret Spider-Man scrapbook before re-reading this and it really was a WHAT? moment. . . Soon after this, Scourge kills Jean DeWolffe’s brother.

Currently in Spider-Man there is a police captain woman who is also the Wraith that strikes me as an attempt to “recreate” Jean DeWolffe (she was friends with her). I really like her character and would love for her to have her own series.

Thanks for commenting!

LikeLike

Very interesting and thought-provoking analysis. I’m not as bullish on the Jean DeWolf story as other Spider-Man fans are, but for different reasons that you list here. My critique comes from the fact that Peter David in one of his first stories was trying too hard to ape Frank Miller’s Daredevil in terms of its noir-ish sensibilities (which was a big problem for Spectacular Spider-Man in general, especially under Owsley who felt like each Spider-book had to be “different” thematically). As a result, we get a foreign version of the Spider-Man character and the whole plot is set into place by the death of a character that was very vanilla and unmemorable to begin with. And the crush angle just felt silly.

With that said, the story is unquestionably different for Spider-Man in a way that I can at least understand why fans love it so much.

LikeLike

I think you are right that David was trying to ape Miller and failing, esp. since he was new to writing comic books, but MOST esp. b/c Spidey just isn’t that kind of character – he can visit that world, but he should never be OF it – if you get my meaning.

Thanks for commenting,

LikeLike

Pingback: Super Blog Team-Up 4: Conan the Barbarian and Solomon Kane | In My Not So Humble Opinion

Great post! (I was directed here thru Longbox Graveyard.) I have those issues, and I remember reading and enjoying them, although now I am disappointed that I did not read them more critically. This brings me to my first point: what age group should read (these kinds of) comics? Let me say off the bat, I agree 100% with your analysis. Spot on. As a young man, I read these comix and they functioned as escapist literature, something to read into between reading heavier works and writing papers, but I should have asked for more. I remember asking in the 80s why US comix couldn’t be more like the Japanese: huge variety: different genres, different interests, different age groups, different genders, etc. So, if we could magically re-write these issues with great writing taking precedence of course, but correcting these egregious errors in “reality”: i.e. having Spidey and DD contend with actual issues of racism and injustice at the hands of state power, who would/could read them? We older well-read putatively cultured and civilized men (women?) might and might enjoy them, but could we give such a book to say an eight year old? Ten year old? Etc. How much grit and realism can be loaded into a comic written for a twelve year old? It seems that the American Superhero comix–the mainstream ones–are growing up for their graying readership and I hope slowly approaching the point where they become actual Literature (with capital L), but I lament that there are not more “in-between” stories, gripping relevant stories for kids who are not mature enough to deal with those important topics in such vivid manner. My point is that this issue (race and crime and law) would be treated differently knowing that your readership is older/younger–and no, it doesn’t excuse these particular books for being cowards or wrong or being misinformed. Next point: your critique is important because it points out how Marvel in this case and in many others tried to assume the mantle of maturity (realism) without actually laying out the racial facets of the problem, thereby only serving to reinforce false norms and beliefs or eventually only supporting one end of the political spectrum. I think the inherent problem in all of this is the superhero genre itself. I mean, I do enjoy it, but at my age I realize it’s totally flawed: you can’t go around beating people up. DD is a lawyer and as you point out, he goes “vigilante-ing” at night? Obviously he’s a criminal or deeply disturbed or both. (He’s both.) So, if we continue to bring reality into these books, they eventually implode. At some point Batman/DD has to realize the best way to fight crime is by fighting poverty and a corrupt or unjust political system, not punching out street-corner drug dealers. This realization makes me appreciate what I think is Kurt Busiek’s approach to the genre in Astro City: if superheroes actually existed, the world would be altogether different and we could definitely apply mature sensibilities to the genre but without danger of the fictional world collapsing under the weight of its own illogic. Discrimination is treated, but through the eyes of people who have become accustomed to people who fly. The average citizens in Astro-City seem to have different sensibilities (and this is a credit to his writing), but they are all of a piece. When Spiderman or whoever has realism injected into his world, it often comes off wrong. The writers have trouble juggling the tropes, the reality, the dictates of their bosses, and this may cause bad writing and cognitive dissonance, at the very least. I think as writers/artists grapple with these topics, however, it also creates great opportunities to craft great stories. I’ve said too much already. Thanks for the essay. Loved it and I’ll follow.

LikeLike

Welcome!

I think you hit the nail on the head when you mentioned (as i tried to) that when writers/artists/editors go to the well of ‘real world’ stuff, whether they mean to or not they bring a lot of stuff with them that remains invisible but is simultaneously glaring.

I also think you are right that the superhero genre itself has a problematic relationship to social problems and narratives of crime. That being said, I prefer “the friendly neighborhood Spider-Man” who fights mob goons or wack-jobs in animal costumes and makes some quips and has an adventure, than the revenge-minded Spider-Man who beats the shit out of guys and doesn’t accept surrender. It is easier for me to suspend disbelief.

I am not saying it is impossible to have a comic title that explore the grim world of crime and social tensions, but Spider-Man is not that comic. Furthermore, i am even more against the 90s penchant to make that “grittiness” into a cartoon in a way that is really offensive, not just clueless.

Ultimately, I think kids are a lot more sophisticated than we often give them credit for, and can handle some dark themes and complex motivations, but still not quite sophisticated enough to closely read and interpret what they are being given (then again, a lot of adults aren’t either), such that when it is “dumbed down” for them it is even more potentially harmful.

LikeLike

First off welcome to the team! Your analysis and writing style was missing from our offerings and boy did you bring it full force!

I am officially a fan! Love the use of panel in this post..the perfect balance of Words to picture to keep the reader into the story without feeling content bloated! (Like my blog at times LOL!!)

Love the Charles Bronson appearance..this story has a very real Death Wish vibe to it and it is clear that the writers were not only using current events of the day in mind but their love of Bronson films as well!

Plus any excuse to use the Black Costume is fine with me!!

Bottom Line..you rocked this thing and we are honored to have you on-board!

Great Work!

Hero Out!

LikeLike

So happy to take part.

I feel a little guilty that I haven’t had much chance to read the other posts and pass on their links individually (though I did tweet the round up I put on tumblr a couple of times) because I have been so busy. But my plan for tomorrow is to alternate reading my new comics with reading SBTU posts as my reward for completing chunks of commenting on the stack of student papers I have.

Cheers!

LikeLike

Awesome man..let us know what you think!!

LikeLike

Pingback: The Comic-Verse: Awesome Art & The Top 15 Featured Links (09/19/14-09/25/14) | The Speech Bubble

Pingback: SUPER-BLOG TEAM Up 4 : Masters Of The DC Universe? | The SuperHero Satellite

Pingback: Forget the Year that Was. . . Imagine the Year that Could Be | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Robocop: Representation By Erasure & The White-Washing of Detroit. | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Power Pack Says Crack is Wack! | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Additions, Corrections, Retractions | The Middle Spaces

I am dredging up this post because of Peter David’s comments at a NYCC panel this weekend (David is the author of “The Death of Jean DeWolfe”), in which he broadly characterized Romani people are child abusing criminals, thus justifying any misrepresentation of them.

You can read about it here: http://www.comicsbeat.com/nycc-16-anti-romani-statements-made-at-x-men-lgbtq-panel/

But in discussing the topic on Facebook, I came across someone linking to a 20009 entry on PAD’s blog, in which in addition to the typical clueless moaning about white people not being able to use the “N-word” while Black people use it “all the time,” and usual “reverse racism” BS, expressed opinions about Al Sharpton that in my eyes confirm my suspicions about how he wrote the Reverend Tolliver character in the “Jean DeWolfe” story. (See post above)

He wrote:

I wish I had seen this back in 2014 when I wrote this post. I would have included it and spent some time with it. Oh well, better late than never.

Oh, and BTW, today on his blog, PAD doubled down on his antiziganism using a specious “think of the children argument.” Sad.

LikeLike

It’s very disappointing what Peter David ranted about at NYCC, as he has been a very good writer over the course of his career. But re-reading this essay was great as well, I feel like I’ve taken it in a lot better than I did maybe two years ago.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Alpha & Omega #3: School of Hard Knocks | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: “Am I Black Enough For You?” The Respectability of CW’s Black Lightning | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Digging Up Ghosts: Teen Titans’ Mal Duncan & His Token Power | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: “I AM (not) FROM BEYOND!” – Situating Scholarship & the Writing “I” | The Middle Spaces