This is Part Two of a two-part series of posts on the classic X-Men comics arc, “Days of Future Past.” Like the first, this part is in a kind of hybrid essay/dialogue format co-written and conceptualized by me and my long-time friend and erstwhile historian, Eric G. While Part One explored our own experiences with reading/collecting X-Men comics in the first half of the 1980s and our feelings about the “Days of Future Past” story arc and its influence on comics in the decades that followed, this part dives into some of the political connotations of the dark future it depicts, especially as it relates to the glaring problem of the X-Men as a generic stand-in for people who are marginalized due to race or ethnicity.

Rather than give another detailed recap of the “Days of Future Past” story from issues #141 and #142 of X-Men, we’ll point you back to Part One of this post, “Days of Future Then” (or you can check out Bronze Age Babies‘ recap/reviews of issues #141 and #142). It became clear to us as we discussed these two issues that the Cold War anxieties obvious in this story point to how our own contemporary moment is a dark future that emerges from the Reagan Era. The metaphor of racial/ethnic persecution is enmeshed in how two white world powers vied for global supremacy through brown bodies, echoing attitudes already present in the national body. It probably bears mentioning, however, that the original story was meant to underscore the very negative consequences of persecuting a particular sector of the population in pursuit of “security,” when there is a belief that some or all of those people are by their very nature a threat to the government and the stability of the nation—there is a direct comparison to the historical events leading up to the Holocaust. To that end, the Senate hearings that the story features as the setting of the action in the “present-day” portion of the story (and remember, that present-day was October 1980) were meant to explore the issue of what to do with these mutant people. As such, it probably makes sense to start our analysis of “Days of Future Past” by exploring the depiction of Senator Robert Kelly, the sponsor for the “Mutant Registration Act,” whose murder was said to precipitate the dark future of 2013 from whence Kate Pryde’s consciousness came.

Osvaldo: It interests me how Senator Kelly is depicted as being a somewhat reasonable figure—with a reason to fear mutant “terrorist” capabilities. He seems earnest in his concern. Not just a villain.

Eric: The specious argument is that X-Men are proof there are some good ones and thus Senator Kelly is wrong, but the “some good ones” argument does not hold water—despite that being the “moral” argument Claremont seems to be making. It suggests that there is some credence to the idea that there are “bad ones,” whose badness is a result of their identity. I could never support laws/illegal action against a group of people no matter what the provocation from some portion of that group. It seems like a big moral leap to go from earnest investigation and considering the possibility of introducing legislation restricting mutants to the last scene which depicts the beginning of the implementation of a secret plan to create giant robots to enforce control over mutants—robots that are known to be dangerous and have turned against their creator at least once.

Osvaldo: I think twice at this point, in X-Men #14 and #57—though I am not sure to what degree the occurrences in those issues were public knowledge. But what I mean by “reasonable” is that Professor X—who as readers I believe, we are supposed to trust and think of as a wise and benevolent custodian of both mutant and human kind—gives Kelly the benefit of the doubt when he is depicted telling Moira MacTaggert to “be charitable…He’s scared. We must teach him his fear is unfounded.” In other words, even the advocate for mutant-kind thinks it is reasonable for humans to be scared of mutants. Now that might work if we are talking about people who can shoot lasers out of their eyes, but when considered in terms of the metaphor of the X-Men series as analog to racial and ethnic hatred and bigotry, it is highly problematic.

Eric: Right. Taken in that light then there is a parallel between the depiction of reasonable fear of humans toward mutants and white liberal fear of minorities—that is not a fear to be charitable about. In fact, considering that there are literally hundreds of super powered beings on Earth in the Marvel Universe the argument for a solution to the “mutant menace” is either ridiculously biased or a cover for the real intention of the Sentinel program, pacifying/retiring all super-powered beings. Given the context of the X-Men metaphor, I would lean towards the former, though in the dark future most of the other superheroes are dead, too. . . so the latter is also a possibility.

Osvaldo: Yes. That bias reinforces the idea that dangerous people of the dominant culture (in this case, non-mutant superheroes) are deemed to be dangerous or not on an individual level, not as members of an identity group. Fear of the minority is coded as reasonable, while fear of the dominant culture is “ridiculous.” It makes me think of Barack Obama’s speech about race when he was running for president the first time. I am no fan of Obama and I was never fooled by his faux-progressivism while running, but at the time I remember being impressed by that speech for its frank and nuanced talk about race as a result of calls for him to renounce Reverend Jeremiah Wright for comments he made in his sermons. In the end, however, Obama had to repudiate Wright anyway. He had to give in to the fear of association white folk have about black folks and other minorities. The obvious “scariness” of one stands in for the “scariness” of all of them. The thing is, looking back now and thinking about that part of the speech where Obama says that his white grandmother was “a woman who once confessed her fear of black men who passed her by on the street, and who on more than one occasion has uttered racial or ethnic stereotypes that made me cringe,” I, myself, cringe a bit. Even though I can sympathize with his claim that he cannot disown her for those views and attitudes because of how devoted she was to him, it plays on the fears of whites when he equates her unreasonable fear—her unwillingness to connect the humanity of her flesh and blood with the humanity of other black men that she might not know—with the comments of Reverend Wright, whose assertions are based on the undeniable material history of white America’s treatment of black and brown people that still goes on to this day. Reverend Wright’s fiery rhetoric in its relation to Obama’s identity as a Black-American is a lot less frightening than Obama as a representative of the establishment with his Kill List and his drones.

Eric: If we are to accept the metaphor as a direct one, and putting into the context of the time period (1980), then at the heart of it, Chris Claremont is just another Democratic liberal who saw Reagan as scary, but also saw minorities as scary; though he doesn’t blame them for their scariness.

Osvaldo: I think the most workable X-Men metaphor is for adolescence—at least, that sense of persecution that often comes with that liminal space between childhood and adulthood, but that doesn’t really consistently work either since, a) the X-Men metaphor is so amorphous that it can be used for a variety of groups, and b) Claremont and other writers have used that ambiguity to get more specifically political when it suits their story needs, like in “Days of Future Past.”

Much like fragmenting alternate futures of X-Men continuity, we saw themes in “Days of Future Past” echoing both the politics of the contemporary moment and the politics of the coming Reagan Era of 1980 when these two issues were released. The 1980 portion of “Days of Future Past” takes place the Friday before what Claremont calls “one of the closest hardest-fought presidential elections in recent memory.” While Marvel Comics used fictional analogues for politicians (most of the time), Claremont would have been writing this right before the Carter-Reagan election. The issues are cover dated January 1981, but were on the newsstand in October 1980, which means they were likely written weeks, if not months before. Clearly, the timing of the “present-day” portion of the story is meant to echo some anxiety regarding the upcoming presidential election.

However, while the “present-day” portion of “Days of Future Past” is often the section of the story that is focused on in terms of the action that matters, as it can ostensibly change the future, the plan that Storm, Colossus, Rachel, Franklin and Logan are attempting in that future is equally as important and resonates with Cold War fears. Sending Kate/Kitty back in time is a shot in the dark. In 2013, it is stopping the Sentinel incursion to Europe and the rest of the world that matters, however unlikely they are to succeed, as it would precipitate an all-out nuclear strike against North America. Essentially, it would lead to the end of the world, and is evocative of fear of a Reagan presidency, which in fact precipitated things like the Euro-Missile Crisis of 1983 almost leading to nuclear war.

Osvaldo: The closeness of the coming election was wishful thinking on Claremont’s part—that it could be or should be hard fought as opposed to the landslide it would turn out to be. The equation of one president winning over the other with the eventual possibility of nuclear war as a result of the actions of the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants seems like a fear of Reagan and the Cold War thing, right?

Eric: We have no way of knowing if Claremont was a Reagan Democrat—probably not—but plenty of supposedly liberal people abandoned the ideals of the Democratic party represented by Jimmy Carter and bought into the fear, both foreign and domestic, that Ronald Reagan was peddling.

Osvaldo: In some ways, I see “Days of Future Past” as a warning about the dark possibilities of a Reagan America. Hell, in some ways I think we are living in the dark future that resulted from Reagan America. So the story could be arguing, “I know these people are made to seem scary, but the cure is more deadly than the symptoms.”

Eric: The separation of people into three categories of citizens—H for human, A for Anomalous Human, and M for Mutant—is at the heart of the dark future projected in issues #141 and #142. Everyone suffers, but the hatred remains focused on the outsider group. It is like those thugs who attack Kate Pryde at the opening of #141. They hate the Sentinels, but they hate mutants more. They blame the mutants for what is happening in the country, even though their current state is a result of the policies of those in power ostensibly enacted to control or restrict the “dangerous minority.” That hatred, like the racism, anti-Semitism, anti-immigrant attitudes it represents, is a convenient distraction from who is really to blame. Fear of the Other is rotting us inside out, causing us to give up whatever tentative freedoms we have, justifying more openly than ever racial profiling and police brutality and making the rest of the world fear us.

“Sentinels are just the glam version of drones.”

Osvaldo: Thus my Obama comparison. Sentinels are just the glam version of drones. The kind of policies that drive the increased use of drones are not all that different from the political stakes in an X-Men comic from 33+ years ago. Clearly it would be hyperbole to say that we are living that dark future that Claremont and Byrne described, but some part of me wants to say that we really are living in that dark future…

Eric: In a way, our future is darker. There is no comeuppance for the racism/xenophobia that comes anywhere near giant killer robots. In the past, we had the Soviet Union as the general threat to U.S. hegemony, which almost leads to U.S. (and everyone else’s) destruction, but instead it just resulted in millions dying in Southeast Asia as well as death squads in Latin America, and dictatorships supported around the world. Our resistance to the USSR in Afghanistan may have led to our modern “war on terror,” but we attack brown people, blame them for the war as well as the rights we lose as a result when it is actually our policies then and now that cause these problems. This way of engaging with the world hasn’t really turned around and bitten us on the ass, yet. Sure, Islamic terrorism could be seen that way, but even 9/11 does not come close to the level of murder and mayhem caused by the Cold War in the so-called Third World. We have yet to deal with our Sentinels.

Osvaldo: The fear of the future is really a fear of some people’s present made national or global. Think about it; that “dark future” with burned out buildings in the New York City that Claremont and Byrne depict was plenty of people’s present in 1980. It’s like Reagan’s use of the Welfare Queen image in his 1976 presidential campaign. He used the racial specter of welfare fraud and freeloaders to distract from the material reality of income disparity that leads to people needing welfare. There is an echo in this story with the irony of Reagan using the fear of the urban to gut the programs that might do something about it, thus making sure his dark future comes to pass. Income inequality is worse than it has ever been. Let’s not forget that the welfare queen/welfare fraud discourse was also part of the Clinton Administration’s “successes” at welfare reform in the 1990s. Democrats are not off the hook for this. The Reagan way of thinking infected all of American politics. The dark future of DoFP is really the tension of the “always present.” Even when Kate stops Destiny from killing Senator Kelly, it doesn’t change the future, because the real precipitating event wasn’t Kelly’s actions, but the ideological systems of state that shape his thinking.

How different is this picture of the burned out Bronx of the late 70s from the dark future depicted in Claremont & Byrne’s 2013 Sentinel dystopia?

The only difference, and the fear that difference highlights, is that rather than the South Bronx, the urban decline has reached Park Avenue.

While it quickly comes to fisticuffs, the X-Men and the Brotherhood are really engaged in a political conflict and both are performing in a political theatre wherein the actions they take resonate with meaning within the existing governing system. Mystique is using her Brotherhood to make a point. They are quite literally terrorists because they seek to enact political change by terrorizing a population. As she says when they smash through the Capitol wall, “As an example of our dread power—as an object lesson to those who would oppose us—we intend to kill him.” The X-Men on the other hand participate in a superheroic version of respectability politics. For example, after Storm uses her powers to blow Wolverine back from using his claws on Pyro, Angel says, “Nice move, Storm. With the country’s growing anti-mutant sentiment, the last thing we need is Wolvie carving someone up—even if it is a villain.” The line depicts his concern with publicity and political expediency. The X-Men are willing to defend those who would enact policies that might lead to their incarceration and death to prove they are the good ones. In the end, however, this effort at respectability does not help their cause. Storm’s conflict with Wolverine (which we discussed in Part One) is depicted as an ethical one—she is opposed to killing—but it is that ethical position that leads to her being in the leadership position, allowing her to dictate a political stance of the X-Men that is in line with Professor X’s philosophy of mutant assimilation.

“With the country’s growing anti-mutant sentiment, the last thing we need is Wolvie carving someone up”

Eric: Based on the ending of the second issue, we can conclude the Brotherhood was right in a way.

Osvaldo: Right. Playing by the rules doesn’t help when the rules are constantly rewritten or selectively enforced against you, especially when no matter how “good” you try to be some other person’s actions are going to be used to judge you happen to belong to the same broad identity group. I think in current continuity some of the X-Men have come to learn that, though I still don’t think murder is the best course of action. The policies that are ostensibly supposed to protect Americans actually actively turn people against America.

Eric: As such, much more widespread and dangerous doomsday scenarios are ignored, or at least become part of a sideshow debate that stall action. For example, catastrophic climate change, which will hurt those causing it the most the least/last. In place of this, those in power want us to think the source of danger really is Islam, undocumented immigrants, Iran getting a nuke, what-have-you.

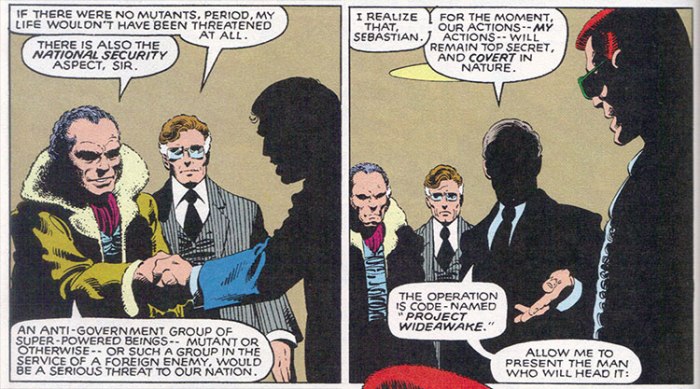

Osvaldo: And let’s not forget, capitalist ideology has learned to maximize its profit and power from war, not from more nebulous global concerns like climate change. Industry sees the concern about climate change as an obstacle to its continued undeterred growth and global reach. It is only an obstacle so long as no one has of yet figured out way to commodify it (and Lord knows those efforts are already underway). Instead, capitalism is presented as a solution instead of the problem. The ending of DoFP really cements it. We see Sebastian Shaw in his role as industrialist getting those orders for more giant robots (i.e. drones or factories, or whatever). As Slajov Zizek reminds us, crisis is not the obstacle to capitalism. Rather, crisis is what pushes capitalism towards permanent extended self-reproduction. It is for this reason that it seems indestructible. It seems that capitalism is like a Sentinel Master Mold, which in the words of Rachel Edidin, is a giant killer robot that poops out more giant killer robots.

Eric: Lockheed-Martin, or whoever, profits from the more obvious and thus more exploitative conflict—so what is the motivation for that conflict to really end?

Osvaldo: Sebastian Shaw can make a profit from building Sentinels…

Eric: And as a member of the Hellfire Club (or the 1%) put himself in a position to snatch power in the ensuing instability.

Osvaldo: And unknown to Senator Kelly and the President as they sign up for the sentinel program, Shaw is a mutant himself…

Eric: Right. We are living in an age of a kind of corporate terror, but the status quo is so entrenched that we seek out corporations to provide solutions. Do you think that at the end Senator Kelly knows what he is doing by backing the super-secret Sentinel plan?

Osvaldo: It’s unclear. I think he sees it as a necessary evil.

Eric: A form of exceptionalism…

Osvaldo: Right. Presidential extra-judicial powers… Kill lists. Sentinels = Drones. Bush/Obama shit. Maybe you’re right, maybe this really is the darker future…

Sebastian Shaw, secret mutant and well-know industrialist. He knows extra-judicial powers are good for business.

In the end, all the X-Men futures remain uncertain, because the only result of all their actions and time-traveling and what-have-you is the creation of more alternate timelines, meaning that the consequences of their actions and inaction, the schemes of foes whether foiled or successful are always shunted off to some parallel world that doesn’t really count. Comic continuity and American politics are both hegemonic systems that seek to delimit and define choices within a set system. Everything else is unthinkable. As a result, both are operating in a state of exception in which the ethics of their actions and that of their foes remain unfixed and unmeasurable. Everything goes, because it is the narrative built around them that matters more than the actions themselves. Reality is forever re-written. Everything done can be undone, and everything undone in some way remains always done. Comics posit that the choice to destroy a world, for example, has no moral weight, if it turns out that destruction was undone. “Days of Future Past” is an apt name, because ultimately the story is about the manipulation of an ever-present fear of a distinctly different future that is clearly much worse than our present and that represents a change from an idealized past. In reality, the incremental nature of change—even change that seems sudden and harsh and monumental like the 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, for example—means there can never be the kind of point of comparison that the Claremont/Byrne narrative allows us to make so clearly. Fear of the future is really fear of the present, because whether that imagined future is a one where mutants rule over humans, humans build giant robots to hunt down and kill all mutants, the vast majority of Americans are of African and/or Latino descent, or Muslim people are put into internment camps, we are really shaping one long living present. There is no future and we are in it.

—————————————————————————————————

Eric G. is a native New Yorker who earned a BA in History from Brooklyn College. A passionate vegan who ran his restaurant Foodswings until it closed earlier this year, he is seeking a suitable focus for the next chapter of his life. After about a 30-year gap in reading comics, he is again reading recent comics recommended by friends with a mix of great pleasure and concern.

Solid post, gentlemen with far-reaching examinations beyond the four-colors that greet the eyes. You guys did some serious delving into basic and not-so-basic elements of this story. Very thought-provoking, and a post I’ll read again. I don’t think I’ll view DoFP past the same way whenever I read it again.

Thanks for your efforts on both posts in this series.

Doug

LikeLike

Thanks, Doug. It was an interesting process of throwing out stray observations and making myriad connections. Once we got going it really was a rabbit hole we had to navigate to keep the topic manageable. Definitely a lot of fun.

LikeLike

Pingback: Days of Future Then: Reflections on X-Men Comics & “Days of Future Past” (Part One of Two) | The Middle Spaces

Agreeing with Doug; very fascinating and thought-provoking post. I really don’t have anything intelligent to add to your overall discussion – other than to nod my head and say, “yep, that’s right.”

One point I would like to make is that I think that all-too-often analyses of these X-stories make a little too much of the mutants as metaphor for various real-world minority groups, in the sense that the various writers like, first Lee, Thomas and Claremont/Byrne, and then later many others, really put that much thought into the metaphor when crafting stories about spandex-clad heroes that were still – until the mid-1980s at least – being written for an audience that consisted mostly of children and adolescents.

So, for example, when Osvaldo says “…even the advocate for mutant-kind thinks it is reasonable for humans to be scared of mutants. Now that might work if we are talking about people who can shoot lasers out of their eyes, but when considered in terms of the metaphor of the X-Men series as analog to racial and ethnic hatred and bigotry, it is highly problematic.”

Yes, in the real world, that kind of thinking is problematic to say the least. But remember, the story is set in a world where there are super-powered beings, some of whom indeed shoot lasers from their eyes. Professor X’s statement seems sensible in that context, in that world, and not necessarily some form of accommodationism.

Also, I have to say I totally agree with Eric in the following paragraph, as he touches on something I found illogical even as a preteen and then teen X-fan: why are mutants so feared and hated, when other super-powered beings aren’t (not as much, at least)? So yeah, there’s definitely something to the idea that the Sentinel program is a cover for the “normals” to keep all of the super-powered types under control.

Anyway, hope that all makes sense: I’m writing this during my break at work, and my brain’s still muggy from a lack of sleep. Osvaldo, last night I ended up reading both of R.S. Martin’s pieces at Hooded Utilitarian (i.e., the 2nd part his Shooter series that I missed, and the latest one on Gerber). I was up until about one in the morning…

LikeLike

Hi Edo! Thanks for commenting.

I think you are kind of just re-iterating what we said about the X-Men metaphor, except I would argue that you can’t use that kind of metaphor (one that has been there since day one and has frequently taken the form of comparison to Nazi Germany and the Holocaust – which makes sense given Lee & Kirby’s heritage and the latter’s involvement in WW2) and when a inconsistency or problem is pointed out, just say oh these are just stories about superheroes for kids! 1) Kids should be given more credit, and 2) they need to start somewhere. (though I am not saying they need to didactic about it).

Anyway, glad you enjoyed our piece – and also glad you got to read those pieces over at HU.

LikeLike

Oh, I’m not trying to say it’s beyond criticism, or that I even disagree with your criticisms here (just the opposite in fact).

I think my main point is that the story is functioning at two levels at least: the metaphorical aspect (which, yes, I even caught as a kid of pretty average intelligence) and on its own terms as something taking place in a fantasy world where there are, in fact, super-powered and potentially dangerous beings, and the dialogue used by Claremont in this specific instance functioned within that context. That is, despite the overarching metaphorical aspects of mutants, maybe not everything uttered by Prof. X or whoever else could or should be extrapolated to our own real world circumstances.

LikeLike

Once again, excellent work at examining particular aspects of this story that I had not previously considered, such as its relation to 21st Century political, economic, social and racial issues in the United States, within both the Bush and Obama presidencies.

Was the Mutant Brotherhood right? If they were, and (as you argue) they didn’t go far enough, then that points to a much larger problem. If the only way to prevent the persecution & extermination of mutants is to overthrow the entire government, that’s indicative of a society & system that is irreparably bigoted. This seems to be a zero sum scenario; either mutants do nothing and are exterminated, or they insure their survival by a bloody coup, meaning the subjugation of humanity.

And where does Sebastian Shaw fit into this? He seems to care nothing for either cause. Shaw is ready to pit the two sides against the other, to exploit human fears and put mutants in grave danger to ensure his own personal power, both economic & poitical.

Which shows why the Brotherhood’s ideology is flawed, because it doesn’t take into account the selfish self-interest of other mutants. Even if mutants did seize control of the world, the next step would probably be the victors splitting into various factions and turning against one another. Rather than the mutant paradise, the “golden age” that Magneto loves to proclaim he will herald, I suspect that a mutant-controlled world would eventually fall into civil war.

LikeLike

Well, I think when Eric suggested that the Brotherhood was “right” (and he can come speak for himself, but since I agreed with him I figured I’d respond), I don’t think he was advocating the violent terroristic attacks they undertake, but the idea that YES, the system is irreparably bigoted, and as such finding out how to undo that system w/o resorting to counter-productive violence is difficult.

I don’t know about Eric, but “not going far” enough doesn’t necessarily mean violence to me, but then again that is part of the problem with politics, its logical extension always seems to be violence and war – and we have a hard time imagining otherwise.

Thanks for your thoughtful comments!

LikeLike

You could probably argue that ANY political system is irreparably bigoted, because human beings are irreparably bigoted. It seems like nearly every society throughot all of human history has had some form of racism or xenophobia or religious sectarianism or nationalistic zeal or political clashes. Maybe it is a part of human nature that we find some sort of random line to divide up “us” and “them.” And if that’s the case, well, like I said, maybe that could justiful a complete worldwide revolution by mutant-kind… but even if mutants won, I still think their “utopia” would be short-lived. In the end, despite their physical differences & amazing powers, mutants are really no more spiritually or intellectually advanced than “normal” humans. Once mutants ruled the would, inevitably they would divide up along some types of ideologial lines, and there would once again be the oppressors and the oppressed.

LikeLike

I guess I don’t adhere to the idea that just because the system a current system will be replaced with will also be flawed is a sufficient reason not work toward fundamentally changing the present one. The Brotherhood of Evil Mutants may or may not have envisioned a utopia (does Mystique use this language? She might, but I don’t recall – if she did and we didn’t bring it up and critique it I count that as a big oversight on our parts), but utopia is way too high a bar to set for determining the value of whatever replaces the system we know is flawed now (as opposed to how it may be flawed later).

Furthermore, I am not concerned with “every society throughout history,” whose issue were specific to their time, politics, economics, geography, etc. . . I am concerned with the American Cold War politics this story seems to be most directly addressing (and that, as we point out, to a large degree we are still dealing with the consequences of today).

One thing I liked about how Quicksilver used to be depict is that, while he did not agree with the methods of the original Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, he did agree with them that humans were dangerous and out to get them and not to be trusted. I liked that he showed there were more than two places to stand on the issue.

Thanks for replying!

LikeLike

My apologies, I didn’t mean to go so far beyond the boundaries of your discussion, and your focus on 20th Century Cold War politics & society. I’m just not terribly fond of the notion that you have to raise a system of government completely to the ground in order to bring about positive change. That’s the sort of thinking that is simultaneously extremist and horribly naïve. Certainly that’s the type of wooly thinking that apparently plagued the Bush / Cheney administration, the idea that U.S. could invade Iraq and overthrow Saddam Hussain’s government, the population would welcome us with open arms, and they’re be a stable, American-friendly democracy in place within a few months.

As for my “utopia” comments, again, I apologize, I was bringing in some of Claremont’s other stories, namely his use of Magneto in Uncanny X-Men #150 and the “God Loves, Man Kills” graphic novel. Magneto is genuinely convinced in both of those stories that if only he can seize control of the world, he will be able to “offer a golden age, the like of which humanity has never imagined!” Cyclops’ response is to say “Magneto’s way is wrong. The peace he offers is illusory. His golden age will last until he dies, if that long. And it’ll end as it as it began — in blood.”

Hmmm, perhaps I should write my own blog post on these controversies. In any case, thanks for listening. Keep up the great work.

LikeLike

You know, I’ve never read “God Loves, Man Kills” – I need to correct that!

I could argue the details of the changes to our system of government or basic policies and priorities it should be based on until the cows come home, but I think we agree that a sudden change of government by force of arms (or superpowers) is a dangerous thing, and it is not often that the results will be stable. “Bloodless” revolutions have happened, and can happen again – except for those that would insist on meeting such a change with violence or the death throes of unchecked state power.

Can we blame reformers and/or revolutionaries if the powers that be respond to their changes with violence, and if so if the counter-response is violent in turn?

LikeLike

Oh, I also meant to say, that I discuss some of these issues in my post about The Beatles’ “Revolution” – https://themiddlespaces.wordpress.com/2014/06/03/so-you-say-you-want-a-revolution-its-gonna-be-alright-just-buy-something/

LikeLike