This is Part One of a two-part series of posts on the classic X-Men comics arc, “Days of Future Past,” which originally appeared in X-Men issues #141 and #142. They are both in a hybrid essay/dialogue format co-written and conceptualized by me and my long-time friend and erstwhile historian, Eric G. The second part will be diving into some of the political connotations of the dark future the story depicts, both in terms of the anxieties of the late 1970s/early 1980s when the series was published, and in regards to the current moment that comic’s dark future was supposed to represent. This part however is a bit of a departure from the usual themes explored on this blog and more about our own experience with Uncanny X-Men, the “Days of Future Past” story arc more specifically, and our thoughts about the influence of “Days of Future Past” on the Marvel Comics that followed it.

This is Part One of a two-part series of posts on the classic X-Men comics arc, “Days of Future Past,” which originally appeared in X-Men issues #141 and #142. They are both in a hybrid essay/dialogue format co-written and conceptualized by me and my long-time friend and erstwhile historian, Eric G. The second part will be diving into some of the political connotations of the dark future the story depicts, both in terms of the anxieties of the late 1970s/early 1980s when the series was published, and in regards to the current moment that comic’s dark future was supposed to represent. This part however is a bit of a departure from the usual themes explored on this blog and more about our own experience with Uncanny X-Men, the “Days of Future Past” story arc more specifically, and our thoughts about the influence of “Days of Future Past” on the Marvel Comics that followed it.

Originally, the plan was to post something about “Days of Future Past” last year, in 2013—the year that the two-issue story depicts as a dark era in which giant robot Sentinels have taken over North America in their unending mission to destroy and/or contain the super-powered mutant threat, controlling every aspect of human life in order to do so and having killed off the vast majority of superheroes, mutant or not, who might try to stop them. However, it never made it into the 2013 schedule of posts, and instead, now that a film adaptation of this story is making it to the big screen on May 23rd, it seemed like a good time to re-read the original issues and examine the story that started it all.

“Days of Future Past” is the story of how the surviving X-Men in a dark future 33 years from 1980—where Sentinels rule North America and most mutants and superheroes have been killed—work to send adult Kitty Pryde’s mind back in time to inhabit her 1980 teenaged body and stop the murder of Senator Robert Kelly, Professor Charles Xavier and Moira MacTaggert at a Senate hearing about the mutant threat. It is supposedly the precipitating event that led to the creation of the Sentinel program. While Kitty (now called Kate) is in the past, getting the X-Men to travel to Washington D.C. to stop the assassination, her friends in the future are undertaking the nearly impossible task of infiltrating the Sentinel headquarters (the former Baxter Building) to make one last ditch effort to stop Sentinel incursion to the rest of the world, which Europe and the Soviet Union will react to by nuking all of North America. This story is rife with Cold War tensions, and there is a sense of a lot being at stake both in the future and present aspects to the action.

One of the interesting aspects to our respective experiences with “Days of Future Past” is that for Eric it marks the beginning of the end of his time reading/collecting X-Men comics, while for Osvaldo the story was from before he even saw his first X-Men comic.

Eric: I think it was with the issue following the death of Phoenix that I began to get issues regularly every month. So, that was what? Issue #138? The last issue of the Uncanny X-Men I remember actually reading all the way through was #183 (July 1984)—the classic issue where Peter (aka Colossus), Wolverine and Nightcrawler run into Caine Marko (aka Juggernaut) at a bar and have a big bar fight—but by then I was already reading sporadically. I lost interest somewhere in the #160s, but to me the series was never the same after John Byrne stopped doing the art, which was the issue after “Days of Future Past.” I did love #183, but wanted to end on a high note, so that was basically it. It’s not like I never looked at other X-Men issues, I browsed, but I think that is the last one I bought.

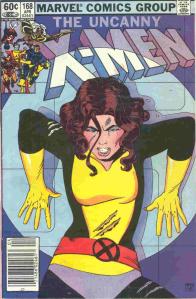

Osvaldo: I had nearly the opposite experience. I started reading on the regular with #168. It was not my first X-Men—that was #144. But #168’s focus on Kitty really struck me. She was my identificatory character. Let no one say that young men can’t identify with heroic young women. In fact, they should. The last Claremont era X-Men I remember getting was some bullshit where they have been brought back to life in Australia and were fighting Mad Max rejects after being killed in the Fall of the Mutants crossover or something. I still don’t know the details and don’t want to know. I don’t care. Issue #226 was the last one I got from the era where I got them on the regular. I remember picking up #231 and maybe a sporadic handful after that and realizing I just didn’t give a shit.

Eric: Nightcrawler and Wolverine were my favorite X-Men. I identified with Nightcrawler because he was the ultimate outcast, but fairly well-adjusted. While Wolverine’s claws were bad-ass and I could imagine his claws being useful for dealing with some school bullies. It was issue #133, when Wolverine is on his own in the Hellfire Club while the other X-Men are held captive, that cemented for me that he was the coolest thing ever, but looking back now, Nightcrawler and Wolverine’s friendship was probably the best example I had at the time–their different perspectives and attitudes complimented each other in ways that appealed to me at that age.

Osvaldo: You were able to quit reading X-Men comics when it was still cool to like Wolverine. ;)

Eric: Back in 1980 Wolverine was almost a completely different character from how I hear he is portrayed these days.

On “Days of Future Past” itself:

Osvaldo: “Days of Future Past” was recent history for me. I was able to borrow the issues from a friend, but they felt to me like from some indeterminate past—evidence of the greatness of a title I would obsessively collect for the next 5 or 6 years, and then only sporadically after that. Only the infamous Phoenix Saga was more apocryphal, mythic. Whether it was ever going to happen or not (and I don’t think it ever did), that kind of apocrypha gave weight to the promise of X-Men continuity providing that kind of pay off once again.

Eric: I loved this comic and I had deep attachment to the characters. Thus, when “Days of Future Past” came out, it broke my mind. First, a cover showing most of the X-Men dead, and then the bleak dystopia so starkly presented happening to a group of people I had come to know—to see these characters eventually all die and to be told at the end that the X-Men’s plan hadn’t worked was thrilling, terrifying and really difficult to hold in my 12-year old head. This was my first exposure to dystopian future. Before The Terminator, The Road Warrior or Brave New World, I experienced “Days of Future Past” and nothing could compare to it. I had not seen anything like it in comics, film or television, and it was profoundly affecting.

Looking back, one of the most amazing things about “Days of Future Past” is that the two-part story is almost like a message sent back from the dark future of superhero comics itself. It is simultaneously representative of the best of the late Bronze Age and a portent of what was to come in the Copper/Dark Age. It is tight and well-paced (if not entirely internally consistent) two-issue arc that serves as an indictment of the decompressed structure in what passes for “events” in Marvel Comics today.

Osvaldo: I cannot help but think that these days the four panels between when Kate (aka Kitty) claims she is from the future and Storm agrees to bring her to Washington DC (FOUR PANELS! WOW!) would be an entire issue of superheroes arguing about whether or not to believe her. The recent Age of Ultron series is an example of that kind of pointless decompression at its worst. It took two whole issues for Captain America to stand up and say something, and what he says is, “I have a plan!”

Eric: “Days of Future Past” tempers the “dark future” stuff with the action in the present. What makes the story work is that despite being compressed into two issues there is some very strong paralleling between the past and the future in terms of character relationships.

Osvaldo: You’re right. I think whether the reader is aware of it or not, it is the echo between interactions in the comic’s present as opposed to the future that give the comic its emotional weight. I don’t know that I ever realized that that was what was making “Days of Future Past” work until you pointed it out. Now I see it all over those two issues—like the relationship between Wolverine and Storm.

Parallel scenes from the future and the present in X-Men #142 that help to inform Storm and Wolverine’s relationship.

We’ll be getting more into the political conflict that informs Wolverine and Storm’s disagreement in the second part of this post, but the conflict itself tells us something about the characters and what is at stake for them in terms of their development. In the present, Wolverine threatens Storm when, in her role as leader of the X-Men, she forbids him from using his claws on Pyro. He second guesses her call in the field. In this still relatively new iteration of the X-Men, Storm is still coming into her leadership position and the rest of her team are coming to terms with it. In the future, on the other hand, when the remaining X-Men are sneaking into the Sentinel headquarters, Storm says to Wolverine, “Let me take the lead,” and all he says is “Okay, ‘Roro. Good luck.”

Eric: Bickering is an X-Men specialty, but there’s none of that shit in the future, which shows both how their relationships have developed and the seriousness of what they are undertaking.

Osvaldo: In the context of the story, this simple, but un-telegraphed paralleling really helps to make the action in both time periods seem like it matters.

Eric: It is a small thing to have Logan defer to Storm so easily in that future scene, but in terms of how Wolverine was depicted back then I think it was a big deal.

There are several examples of these narrative parallels: Kitty and Peter’s relationship in the past and future, the limit to Wolverine’s healing factor with nearly being burned to death by Pyro in the present and having the flesh seared off his adamantium-laced bones in the future, and Kitty’s discomfort with Nightcrawler’s demonic appearance in her present neophyte X-Men version as opposed to her clear love for Nightcrawler once her brain is switched with her future self.

Osvaldo: The sense of change between time periods matters, since at least in 1980 readers could believe that these characters might still be allowed to grow old and change. This dark future was a real potential future. It was not yet an “alternate” future.

Eric: It’s interesting because in a way it is less bleak of a story because we feel like there is a chance to change it, but those future deaths hurt more because we are looking those younger characters in the face as we see the horrible fate potentially awaiting them.

Osvaldo: Right. When all futures became alternate futures and thus alternate universes, there was less at stake. I love What Ifs and alternate worlds, but Uncanny X-Men became a victim of its success in depicting its future. Eventually they went to the well one time too many. As Louise Simonson who edited X-Men at the time says in an interview in Sequart’s documentary Comics in Focus: Chris Claremont’s X-Men, the success of things like “Days of Future Past” and self-contained crossover stuff like “The Mutant Massacre” led to editorial’s demand for yearly “big event” crossover stories. They not only lost their specialness. It became impossible to ignore their absurdity.

It is for this reason that 10 issues of something like the recent Age of Ultron can never have the pathos of two issues of X-Men from 1980—from the beginning it was clear that none of what was happening in Ultron going to matter or stick, to the point where even within the context of its own story there was never a sense that anything was really at stake. “Days of Future Past” is a synecdoche for the dark tone and surfeit of “event comics” that followed in the 80s and 90s and even current mainstream superhero comics. It has everything those later comics have: death, graphic violence, doom, a sense of no clear victory, inter-team conflict, alternate worlds and time travel. It is because of what “Days of Future Past” establishes that the unwieldy continuity of X-Men comics is even possible, and yet it is Claremont and Byrne’s ability to succinctly include all of these aspects that makes these two issues shine. It feels both complete and open-ended in that the particular plot of the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants is thwarted in the present, but the future is still uncertain as the last scene in the comic reinforces (a scene we cover in detail in part two). And yet that uncertainty allowed for room for endless riffing on the dark future as origin.

X-Men Annual #14 was part of the “Days of Future Present” crossover from 1990, that also included Fantastic Four Annual #23, X-Factor Annual #5, and New Mutants Annual #6.

Osvaldo: The first real sequel to “Days of Future Past” was the crossover event “Days of Future Present.” I have never read it.

Eric: Neither have I. But then again, Mutant Massacre, Fall of the Mutants, Inferno, I’ve never read any of that.

Osvaldo: But I feel like “Days of Future Past” became the blueprint for every major X-Men event that came after it. Even when a story arc did not include an alternate future (and many of them seem to, whenever I try to bolster my X-knowledge online I run into references to shit I have no idea about, like the “Apocalypse timeline,” whatever that is), they still involve characters that are to a great degree informed by that stuff. Later the coolness of these alternate futures was just an excuse to depict grizzly deaths of our favorite characters.

“Days of Future Past” also marked the introduction of the New Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, led by Mystique. They have an important role in moving the action along in the “present” portions of the story.

Eric: The new Brotherhood of Evil Mutants are against the government, but operate inside of it–or at least literally hide within it.

Osvaldo: While the older version of the Brotherhood (the one led by Magneto) was meant to be the “evil” counterpart to the X-Men, I think this new version of the group fulfilled that role in a more interesting way.

Eric: There was the parallel in Storm and Mystique as leaders—both women. I love that one woman is leading a “brotherhood” and the other leading the “X-Men.”

Osvaldo: Both dealing with volatile personalities—Wolverine and the Blob respectively. But I also think that there is an echo between the groups politically. While Professor X was not a shape-shifter he had more than one identity. On the one hand he works as a public political advocate for mutants, appearing before a Senate sub-committee and giving testimony, etc… On the other hand, he runs a mutant paramilitary organization that takes it on themselves to police the mutant population towards an assimilationist agenda. Mystique is doing something similar. In her Raven Darkholme guise, she works for the Pentagon and manipulates the powers that be, while also running a kind of mutant terrorist cell bent on domination of humans.

Eric: If Magneto were still leading the Brotherhood you would have a simple juxtaposition between the groups trying to kill one another in the present and being allies in the future–but he isn’t. Instead, we can assume that none of the villains ostensibly responsible for precipitating the future events survived. So perhaps, based on the ending of the second issue, we can conclude the brotherhood was right in a way, but should have been more aggressive in killing off US leadership.

Later (Uncanny X-Men #199), this incarnation of the Brotherhood would become the government-sanctioned group Freedom Force—the irony being that the government was willing to hire mutant villains to bring the “hero” mutants to justice. This is a bizarre articulation of power, collapsing the “evil” mutants with the well-intentioned, but over-zealous, anti-mutant sentiment of the government.

Later (Uncanny X-Men #199), this incarnation of the Brotherhood would become the government-sanctioned group Freedom Force—the irony being that the government was willing to hire mutant villains to bring the “hero” mutants to justice. This is a bizarre articulation of power, collapsing the “evil” mutants with the well-intentioned, but over-zealous, anti-mutant sentiment of the government.

Eric: DoFP is also less than a year before in introduction of the more complex Magneto (X-Men #150), with his revealed origin as a survivor of the Holocaust. It makes sense to have him disassociated with the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants.

Osvaldo: True, and returning to the paralleling we talked about before—Magneto of the future is an ally of the X-Men, just as he would eventually become an ally of the X-Men in the present time-period (or at least the near future). In fact, in the future, he is in a wheelchair like Professor X—a little echo of his being headmaster of the school one day? There was a strong sense of Claremont having long term plans for his X-Men run, even if eventually those plans would get away from him in a way that would make the title suffer. I wish comics would go back to the pacing of two-issue arcs, with one-shots thrown in-between and the very occasional three-to-five issue story.

And what about the art in “Days of Future Past”?

Eric: John Byrne’s takes on the X-Men are iconic for me, like a bug perfectly preserved in amber, those characters are locked in my head as they appear in those issues. Terry Austin’s inking certainly helped, too. I know it’s been noted before, but Austin’s inks lifted Byrne’s art to heights he never reached with other inkers.

Osvaldo: I am big fan of Byrne’s art and writing. I love his Fantastic Four and his She-Hulk. So, for me while I love his art in these two issues and other X-Men of this era, it is probably John Romita, Jr’s pencils that stick in my mind.

Eric: I do think Byrne’s drawings and Austin’s painfully detailed inking brings a deep, gritty realism to the dystopian future (the details of the derelict buildings, the sewers, etc.). I think his depictions of Wolverine being burned to death and Colossus crying when Storm is killed, drives the emotional depth as much as the words on the page.

Osvaldo: I agree. I also love his paneling and the movement it suggests, especially in the Washington D.C. fight. Pyro’s flame constructs look great, too—though that is also because of the coloring (by Glynnis Oliver, though I think the coloring was touched up in the collected edition I own).

It is pretty clear that “Days of Future Past” is about as important an X-Men story as there is. It is the seed from which so much of X-Men history would grow from, including all the late 80s and 90s stuff that neither of us have much interest in. It is so jam packed that having spent a lot of time with these two-issues has given us a new appreciation of it, but also it also became clear how it is informed by problematic political assumptions, and that the dynamics it portrays in terms of the title’s on-going metaphor as plight of the racial/ethnic Other. It is this aspect that we will be focusing on in part two of this post, “Days of Future Now.”

—————————————————————————————————-

Eric G. is a native New Yorker who earned a BA in History from Brooklyn College. A passionate vegan who ran his restaurant Foodswings until it closed earlier this year, he is seeking a suitable focus for the next chapter of his life. After about a 30-year gap in reading comics, he is again reading recent comics recommended by friends with a mix of great pleasure and concern.

Well done, gentlemen! I enjoyed your take on this classic story, and you nailed the “conversational” element if I do say so!

Doug

LikeLike

Glad you liked it, Doug. Part Two is coming next Tuesday. Hope you’ll come back.

Thanks for commenting!

LikeLike

Thanks. It was fun to work on once we figured out a suitable presentation.

LikeLike

Pingback: Days of Future Then: Reflections on X-Men Comics & “Days of Future Past” (Part One of Two) | That Dark Alley

Really great stuff. Great point about Wolverine’s temperament being so different. The wanted poster cover will always be one of my all-time favorites; it cemented Wolverine as not just a, but THE, badass. Great job, y’all!

LikeLike

Yeah, great job guys, and a very interesting and thought-provoking post. However, I think I’ll save any further comments until the second part goes up.

LikeLike

Pingback: Days of Future Now: Reflections on X-Men Comics & “Days of Future Past” (Part Two of Two) | The Middle Spaces

These issues went on sale immediately after I started college — at which point I had been reading X-Men comics for twelve years, starting with issue #50 or thereabouts — so it’s fascinating to see how readers with such different histories and entry points into the series can arrive at much the same place. That you still feel the impact of these issues even coming at them almost from the opposite direction, chronologically speaking, says a lot about the overall effectiveness of the story.

There’s one thing you don’t really focus on here that could use a closer look. In previous issues we got to know Kitty Pryde, a precocious and sometimes insufferably precious thirteen year old. We open the first page of this story and with no warning (apart from the cover, apparent only in retrospect) suddenly we’re with a grim, haggard Kate Pryde in her late forties, looking back at the misery her life has become. Nothing like that had been done in comics before. The closest parallel I can think of is the occasional “imaginary story” at DC where Superman has an adventure with a now-grown Adult Legion of Super-Heroes, or Robin has grown up to become the new Batman, with Burce Wayne’s son as the second Robin. We certainly never saw a teenager grown and crushed by the sorrows of middle age.

For me, that’s what Days of Future Past was really about: the horrible feeling of an adult that it all went wrong, this wasn’t the way the future was supposed to happen, and if only you could go back and undo that one terrible mistake and do it right, things could be the way they were supposed to be. When Kate goes back into her past, it’s an apt metaphor for what we actually do: relive that moment over and over in our thoughts, wanting to step back and be there again. That image of a middle-aged Kate, full of bitterness and regret, hit me like a fist in the gut when that comic came out. And if it meant that much to a teenager, it means even more to read it again now in my fifties.

Incidentally, this is why I lost any interest in seeing the film version. I have no great desire to see what should have been Kate’s story now that it was turned into Yet Another Wolverine Film. (But I might just rent Peggy Sue Got Married and watch that again instead.)

LikeLike

That’s really a great point about Kitty/Kate. I had not considered that, but it makes perfect sense (and dovetails nicely with my point in Part Two where I say that adolescence might be the best of the many-fold X-Men metaphors).

I saw the film today and was distressed that so much of the political subtext was stripped from it. I mean it is still there as a kind of vague suggestion, but unlike Captain America: The Winter Soldier, for example, it does not even attempt to engage with the broader political implications of its story.

LikeLike

That really is a huge part of the pathos of the arc. I remember almost tearing up after Kate’s embrace of Nightcrawler, which of course was a great, simple way to show how much Kate missed all she lost.

I’ll be watching this movie on free cable some day.

Thanks for the insightful comments.

LikeLike

Wow, really insightful analysis. It’s great that a story that was written three decades ago is still open to interpretation. I never really considered the parallels between Xavier and Mystique (dual identities, with each masquerading as a non-mutant) and Ororo and Mstique (forceful women leading a group made up mostly of men which contains a stubborn, macho type who refuses to take orders).

Mystique is a seemingly perplexing character. She is ready to commit casual, brutal murder on a regular basis. Yet she genuinely loves Destiny, whom she has been with for decades (years later Claremont was finally able to come right out and state Raven and Irene were romantically involved). Mystique also starts out ostensibly fighting for the cause of mutant rights. But at the first chance, given an offer of amnesty if she comes to work for the federal government, she does a complete & total 180 turn and works to hunt down “unregistered” mutants. After pondering the character for some time, I came to the conclusion that Mystique’s primary motivation is her own personal survival. She will embrace whatever ideology or methodology that is most likely to ensure her safety & security, and she’ll switch sides at the drop of a hat, as soon as the winds shift.

LikeLike

Thanks for the thoughts, Ben. When I was considering an article on these issues it was torture but once Osvaldo and I began a discussion on the story, it just built momentum at every turn. Rediscovering the story and seeing how much is there for investigation, I am just constantly amazed it all happened in two issues.

LikeLike

Pingback: Forget the Year that Was. . . Imagine the Year that Could Be | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Imperfect Storm (Part One): Exploring “Lifedeath” | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Jack-in-the-Box: Race & Legacy Superheroes | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: Like a Phoenix: On Selective Completion & Re-Collecting X-Men | The Middle Spaces