Editor’s Note: Today’s post is the first in we what we hope to be many more guest posts. If you are interested in writing something for us, click the “Submit” button on top and contact us.

The New Teen Titans #1, published by DC Comics in November 1980, brought together the classic sidekicks Robin, Kid Flash, and Wonder Girl, as well as perennial outsider Beast Boy, now called Changeling, and added Cyborg, Raven, and Starfire to the mix. All of them were adolescents, and all of them were dealing with parental issues in some way. Written by Marv Wolfman and drawn by George Perez, the concept was a fairly simple one, that of a superhero team made up of teen sidekicks and wanna-be sidekicks having their own adventures sans adult supervision. Even their origins as a team emerge from the superheroic version of parental drama—they were brought together by the mystic manipulations of Raven in order to fight her demonic father, Trigon the Terrible. This was not the first incarnation of the Titans. Teen Titans was first published in February 1966, running until February 1973 (which were drawn for a long while by the recently deceased Nick Cardy), and three years later the title was renewed, picking up with the same numbering. But it was not until the original trio of Titans were aged to become young adults (whether this meant making them older or younger depends on one’s view of the confusing mess of DC continuity, and joined by Changeling, as well as newly created characters Raven, Cyborg, and Starfire, that the series really took off. The earlier incarnations of the Titans were didactically focused on helping other teenagers, eventually evolving to also focus on social issues of the time, including the specters of racial tension and the Vietnam War. But it was the Wolfman/Perez series that allowed them to grow beyond their initial, somewhat limited concepts as merely sidekicks, and allowed readers to identify with them as a team of young adults coming into their own, rather than as individuals forever in the shadow of their mentors. The influence of these mentors and guardians weighed heavily on their young shoulders, and the resultant tension and anxiety as they attempted to define themselves as (a team of) individuals, rather than as sidekicks, is what defined The New Teen Titans.

From a re-telling of Robin’s origin in Batman #213 (August 1969)

But, I’ve always loved sidekicks. Robin, the original sidekick, was created by Bob Kane as an attempt to increase sales by allowing young readers to see themselves in Batman’s adventures, flipping and kicking and jumping around—helping Batman take down the bad guys (Wright 38). And it worked. I always liked Batman, but he was so gray and stern and far too old. I wanted to be a superhero, but I didn’t necessarily want to grow up. I wanted to wear the red, green and yellow, half cape, pixie boots, and all. Being the sidekick superfan that I was (and am), it’s not hard to see how I would react to the publication of The New Teen Titans. Excited doesn’t even begin to cover it. I saved my allowance, raided my piggy bank, and forced my mom to take me to the drug store two or three times a week. There was no way I was going to miss a single issue of what quickly became my favorite comic book of all time.

Part of what made New Teen Titans so appealing to me (aside from their costumes—Kid Flash’s reverse of the Flash’s red and yellow motif and visible hair improved on a classic) was its focus on the kinds of psychological issues that sidekicks have—issues that made them more like Marvel characters than the indomitable Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman (and more than one fan and critic has made a point of calling the Teen Titans DC’s answer to the X-Men’s overwhelming popularity). Sidekicks deal with all the problems of being a superhero along with all the problems of being an adolescent, although prior to the Teen Titans such problems weren’t often featured on panel or in-continuity. There’s a reason that Marvel characters like Spider-Man were so popular and so different from the DC paragons that founded the superhero genre, and while it might have a little to do with his costume and powers, it’s his problems and how he deals with them that makes him compelling. Spidey was a teen hero with real problems and real flaws, a protagonist still in development rather than an already developed adult, allowing him to evolve and grow as a character, something not often seen with DC’s icons.

Part of what made New Teen Titans so appealing to me (aside from their costumes—Kid Flash’s reverse of the Flash’s red and yellow motif and visible hair improved on a classic) was its focus on the kinds of psychological issues that sidekicks have—issues that made them more like Marvel characters than the indomitable Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman (and more than one fan and critic has made a point of calling the Teen Titans DC’s answer to the X-Men’s overwhelming popularity). Sidekicks deal with all the problems of being a superhero along with all the problems of being an adolescent, although prior to the Teen Titans such problems weren’t often featured on panel or in-continuity. There’s a reason that Marvel characters like Spider-Man were so popular and so different from the DC paragons that founded the superhero genre, and while it might have a little to do with his costume and powers, it’s his problems and how he deals with them that makes him compelling. Spidey was a teen hero with real problems and real flaws, a protagonist still in development rather than an already developed adult, allowing him to evolve and grow as a character, something not often seen with DC’s icons.

Sidekicks make their mentors more interesting, and provide the family dynamic that was often missing from DC superhero comics (or beyond bizarre when it was included), which dealt primarily with modern day gods in primary colors smashing one another and making drawn out speeches about their intentions. The introduction of this family dynamic allowed writers to explore the humanity and even weakness of characters like Superman and Batman, who may have been near perfect in their approach to supervillains but suffered the same inexperience and anxiety when it came to their wards as any parent does. Sidekicks humanized the godlike beings who taught them, but it can be smothering to grow up under the wing of a demi-god.

Sidekicks make their mentors more interesting, and provide the family dynamic that was often missing from DC superhero comics (or beyond bizarre when it was included), which dealt primarily with modern day gods in primary colors smashing one another and making drawn out speeches about their intentions. The introduction of this family dynamic allowed writers to explore the humanity and even weakness of characters like Superman and Batman, who may have been near perfect in their approach to supervillains but suffered the same inexperience and anxiety when it came to their wards as any parent does. Sidekicks humanized the godlike beings who taught them, but it can be smothering to grow up under the wing of a demi-god.

In his book How to Read Superhero Comics and Why, Geoff Klock argues for the appropriation of Harold Bloom’s anxiety of influence poetics for comic book criticism. Klock claims that

[s]uperhero comics are an especially good place to witness the structure of misprision [a strong and deliberate misreading], because as a serial narrative that has been running for more than sixty years, reinterpretation becomes part of its survival code. Bloom would suggest that novels, poems, and plays, often viewed as closed structures, are best seen in a continuous line with the history of their literature, a paradigm Batman fans have known for years.” (13-14)

I’d like to take this idea a bit further, though, and suggest that an understanding of the anxiety of influence is required in order to really understand sidekick superhero comics. As with any other recurring comic book character, the anxiety of influence is seen in the tension created by the attempts to tell new stories with old characters (who gain more and more continuity baggage with every appearance), but this is doubly the case with sidekicks, whose very identity is permanently enmeshed with a pre-existing, more popular character. You can’t read Robin without knowing Batman; the sidekick cannot exist in a vacuum. Batman may rarely show up in the pages of The New Teen Titans, but his influence shapes every aspect of Robin’s character. Even later when Dick adopted the guise of Nightwing, this new “darker” identity was still informed by the Dark Knight. The same can be said to a lesser extent for Kid Flash and Flash. This enmeshment is literally true for Wonder Girl, who didn’t exist prior to her first appearance in the previous incarnation of the Titans. Originally, Wonder Girl was just a younger version of Wonder Woman and not a separate character. Writer Bob Haney accidentally assumed that she was WW’s sidekick and introduced her into the 1960s Teen Titans team as an independent character. The discovery of the mistake was caught shortly after publication and DC quickly rewrote WW’s mythos to include Wonder Girl, now given the name of Donna Troy, a child that Diana rescued from a burning building and brought back to Paradise Island, where she was adopted by Queen Hippolyta and raised as an Amazon. Wonder Girl was born from misprision regarding Wonder Woman’s past (and the need for a teen female superhero), much like Athena from the head of Zeus, and thus always operated as an extension of the Amazonian icon.

The anxiety of influence helped make The New Teen Titans young adult literature before young adult literature was cool. One of the most important aspects of young adult literature is that it creates a fictional environment in which the anxiety and fears of children are expressed through an engaging plot-driven narrative. All children deal with the anxiety of their parents’ influence as they seek to become their own person. They must grapple with a future that is inextricably linked to their parents’ past, as parenting is an ongoing attempt to construct one’s children’s worldviews and future identities. Like Harry Potter, Robin and Changeling also lost their parents to violence at a young age. Changeling lost his adoptive parents as well, and Robin was raised by an emotionless paragon of human potential who couldn’t be bothered to actually adopt him. Raven’s father was Trigon, an extra-dimensional Satan who was determined that she join him in his attempted domination of the universe. Wonder Girl’s past was a constantly shifting mystery. Starfire was sold into slavery by her older sister. Cyborg’s father never supported his athletic aspirations, and ended up causing the inter-dimensional accident that killed his wife and left his son disabled. Kid Flash was the only one with anything close to a stable upbringing, but even stability is no shelter from the peril of adolescent love, especially when dealing with Raven magically forcing him to fall in love with her.

It wasn’t just the relatable issues that the Titans had to deal with that made their title such a hit (The New Teen Titans was one of the few DC titles to regularly compete with Marvel’s Uncanny X-Men for 1st place); it was the way they dealt with those issues. Ironically, a title featuring super-kids featured some of the most realistic and relatable storytelling DC had to offer at the time. The Titans argued, they fought, and they fell into fits of depression. They were insecure on the inside and all braggadocio on the outside. They were a family, and even if that dynamic wasn’t explicit, it was apparent. They grew up together. Even their villains reflected the problematic nature of parent/child relationships. Deathstroke the Terminator was the typical distant father whose job was more important to him than his two children; one of them, Joey/Jericho (who’d later join the Titans), lost his voice due to Deathstroke’s hubris, and the other, Grant/The Ravager, underwent an untested version of the same surgery that gave Deathstroke his powers. The surgical procedure was flawed and he died in his father’s arms—his death was the literal result of his attempt to become just like his dad. Family and the attempts of children to define themselves as individuals shaded every issue of The New Teen Titans.

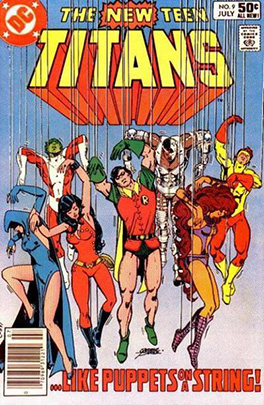

Additionally, Wolfman and Perez’s long partnership allowed them to craft storylines that played out over years, rather than six issue arcs. Over the course of the first ten issues, the Titans fought and defeated an alien invasion, Deathstroke the Terminator, Satan/Trigon, the Fearsome Five, the Puppetmaster, H.I.V.E. and even their mentors—all while dealing with their own insecurities and complex family dynamic. Later on they’d even crossover with Marvel’s X-Men and face down Darkseid and Dark Phoenix. And yet none of it felt rushed, and the emphasis was always on how these conflicts influenced or symbolized manifestations of their personal interactions and development, as seen in The New Teen Titans #6, when Raven refuses to emulate her father, even after joining him in order to save Earth. She heals a girl Trigon has fatally wounded, only to watch in horror as Trigon kills the girl immediately afterward just to teach her a lesson. Raven’s quest to defeat Trigon was a heroic and mythic one, saving the universe from eternal slavery to Satan, but it was also a personal one, establishing herself as separate and different from her father.

A young girl pays the price for Raven’s disobedience (from New Teen Titans #6, 1981)

The New Teen Titans brought a kind of exploration of characters not typically seen in DC’s superteam books. Yes, there was always another climactic battle around the corner, but it was their attempts to step out of the shadow of their mentors that were the far more exciting and satisfying narrative elements. Wolfman and Perez created a title that resonated with adults and children alike, one that was critically and commercially successful, and their success has rarely been matched in the realm of superhero comics since. They took characters that for the most part were little more than extensions of DC long-standing characters, and demonstrated to full effect the many ways in which those influences shaped their development into fully realized characters that could stand on their own. Or at least, together they could stand on their own. As a kid, The New Teen Titans helped me to realize that my own problems were not unique, nor were they insurmountable. Furthermore, they taught me this in a way that was never overly didactic and always entertaining. “Titans Together!” wasn’t just a battle cry, it was a strategy for growing up and surviving in a world that wasn’t always fair or pretty or nice, a struggle shared by the adolescents that read The New Teen Titans, who likely saw themselves and the Titans as all being in it together. Regardless of one’s background and circumstances, the Titans provided a sense of family to the reader and a way to collectively overcome (if only temporarily) the anxiety and fear of growing up between an unknowable future and the all-too-familiar models for adulthood. “Titans Together!” was a way of life.

Charles A. Stephens Jr. attends Texas A&M University-Commerce, where he’s finishing up his doctoral work in literature, with a focus on film and graphic narrative, while teaching argument and rhetoric to impressionable freshmen. His dissertation analyzes the British Wave of comic book creators, led by Alan Moore, and their influence on American comics, via literary historical analysis of the title Hellblazer and the character, John Constantine. A diehard Grant Morrison fan and devotee of the Brit Wave, he loves almost all genres of music, beef jerky, metafiction, and bad cheerleader/dance movies. He is accompanied almost everywhere by his sidekick Flash the beagle. Check out more of his musings (and nag him to write more!) at http://cstephensjr.tumblr.com/.

Thanks for sharing your work with us, CJ!

While I think the idea of the “anxiety of influence” is important as Klock applies it to comics, not only am I pretty sure Bloom would balk at its application to comics, I think Bloom in general is the quintessential trumpeter of the dead white men school of literary criticism, who doesn’t seem to realize that his claim that politics have no place in such criticism is a political position in itself.

The thing that really interests me with the topic is the intersection of art (developing new stories and looks from the established characters and their traditions) and marketing that is seeking to put existing brands to work (the core superheroes’ sidekicks) to emulate the success of their Marvel competitors (X-Men). How do the market considerations of comic book publishing serve as a form of influential anxiety to comic creators? (the kind of thing, Bloom as a dedicated aesthetician would likely ignore).

Take for example the X-Men/Teen Titans crossover, that had to be more in DC’s favor than Marvel – I know as a dedicated Marvel Kid, I never considered getting a DC comic at that time until I saw the Teen Titan x-over and thought they might be cool. How do you handle the pressure to make existing characters more “Marvel-like,” while maintaining the DC aesthetic (however broadly that may be defined)?

LikeLike

I agree with you on Bloom. The fact that he’d likely shit a metaphoric brick over his work being used in comics studies only makes the whole deal that much sweeter to me. Appropriation so often comes about when those in power take from those without, so I appreciate the irony when it works the other way…

Good point on the anxiety created by market forces, as it’s the sorta thing that’s always been a major consideration when dealing with art. It’s all about the art, until you realize that without some kind of market for it, even great art runs the risk of being ignored. So how far is the artist willing to “taint” his/her vision in order to reach a wide enough audience for that art to have any sort of societal effect?

Honestly, other than the breakdown between iconicity (DC) and character (Marvel), I don’t know that it’s easy anymore to differentiate between the two… DC used to always tell stories about nearly infallible godlike beings, which sounds like a good mythological connection until you realize that most mythic deities are definitely NOT infallible. I definitely think Marvel’s approach (telling stories about humans who happen to also have some godlike abilities) affected DC in a huge way, and perhaps had the 90s not been devoted so much to psychotic heroes in name only, we might have seen a much better evolution of the superhero as human…

LikeLike

Huh. Thought I edited my settings to display my identity as Charles Stephens instead of ninjajester. Oh well. ninjajester=Charles Stephens. I’ll figure out the settings thing one day…

LikeLike

Interesting article, Charles. I particularly agree with your points about what made the series so compelling, i.e., the emphasis on an almost familial dynamic between the team members, as well as many of their adversaries representing various aspects of the bad parent/father (Trigon, Deathstroke, that mean old rich guy that wanted to join HIVE…). I also found it interesting that actual family problems/conflicts were worked out in some of the stories, like Changeling dealing with his step-father and surrogate family in that Doom Patrol story line, Cyborg eventually making peace with his father, or Starfire confronting her vile older sister.

However, there’s one facet of your thesis that I don’t agree with: the emphasis on the Titans’ status as sidekicks. I think what made NTT so compelling, and such a smashing success, was that the sidekick aspect – and really any dependence upon or need for approval from their mentors – had been almost entirely discarded. The three new characters were nobody’s sidekicks, while Robin, Wonder Girl and Kid Flash in particular had completely moved out of the shadow of their mentors from the very first issue.

Osvaldo’s point about marketing is quite salient here: Wolfman and Perez, and I assume DC editorial, very much wanted a team and a book that resembled the X-men, and would hit the same buttons on readers that the X-men did.

Incidentally, I find it interesting that you liked sidekicks like Robin so much because you had a character with whom you could identify. It was almost the opposite for me: I didn’t mind sidekicks, but as a preteen and then teen reading comics I had no problem identifying with the “adult” characters, i.e., the early twenty-something Spider-man, Iron Man, the Thing or, especially, the X-men. In fact, I initially hated Kitty Pryde when she was introduced to the latter title, even though I was just a little younger than she was supposed to be at the time.

(Apologies for the lenghty comment…)

LikeLike

You make some good points, Ed, and thank you for reading. And you’re right, the three new characters were not sidekicks. Perhaps I could have found a better word to use, although adolescent superhero seems a bit clumsy a term to use repeatedly. But Robin had issues with Batman that showed up in their crossover with the Outsiders, around issue #37, and his assumption of the Nightwing identity, around issue #39, had everything to do with getting out from under Batman’s shadow. There’s also issue #4, where the Titans were forced to fight the Justice League, pitting Robin, Wonder Girl, and Kid Flash squarely against their mentors due to the JLA not identifying Trigon as the threat he was. And I guess I might’ve leaned too heavily on Robin in these arguments, but in that respect I’d argue that Robin was the lynchpin of the New Teen Titans. Raven may have brought them together, but he was the one who held them together. And it’s apparent, I think, in the names Kid Flash and Wonder Girl that while they might not have had as smothering a relationship with their mentors as Robin, they were unable or unwilling to step out from the shadow of their mentors, for whatever reason.

But as I said, you have a valid point. My thesis works better if I simply broaden it to be entirely about adolescent superheroes and their parental issues, whether those parent figures are superheroes or actual parents. But I maintain that even without Batman’s presence in the Titans, Robin is pretty hard to read and fully understand without understanding his connection to Batman.

Regarding the Titans/X-Men connection (and your mention of Kitty Pryde), I don’t have the source in front of me, but I’m pretty sure that Wolfman has commented on that very thing before, remarking that the introduction of Terra was a response to the introduction of Kitty Pryde, and that he used the audience’s expectations about a young female teenage superhero, insecure in her power, against them. Terra was bad from the start, but fans still expected some sort of turnaround where she embraced her good side, in spite of the fact that there wasn’t any textual evidence within the Titans comics that she really even had a good side.

I really can’t say why I identified with teen superheroes so much, other than the fact that they were more easily equated with me. And I loved the bright costumes most teen heroes wore. It wasn’t until I was a broody almost adult that I grew to appreciate Batman’s grim appearance.

Again, thanks for reading. I appreciate your feedback, and am happy to (virtually) meet another Titans fan.

LikeLike

Pingback: 2013: Reviewing The Year It Wasn’t | The Middle Spaces

Fantastic article! You really summed up the Titans and why they appeal to folks. You get the A+ teenage sidekicks hunger for!

LikeLike

Pingback: Forget the Year that Was. . . Imagine the Year that Could Be | The Middle Spaces

Pingback: YA = Young Avengers: Asserting Maturity on the Threshold of Adulthood | The Middle Spaces